Archive for December 30, 2012

Whooper Video

December 30, 2012A WHOOPER NEW YEAR TO ALL

December 27, 2012by Chester McConnell

The Whooping Crane Conservation Association wishes Operation Migration, Florida, Louisiana, International Crane Foundation, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and all of our citizen supporters a Whooper Happy New Year. We hope for continued success of the several whooping crane programs. All our combined efforts are essential to help reach the goals described in the International Recovery Plan for the Whooping Crane.

Each private organization and agency has its own program but another very important element to the success of all programs is the tremendous contributions of the private citizens. They assist us in many ways including moral support, contributions of dollars, spreading the message and reporting observations. I want to give recognition to a special group of citizens who observe whoopers and take the time to report their sightings.

The Whooping Crane Conservation Association’s web site includes a “Report A Sighting” section where anyone can let us know about their observations of whooping cranes. We receive reports from many states and several provinces in Canada. While the vast majority of the reports are accurate a few actually turn out to be other large white birds with black wing tips (such as wood storks, white pelicans, snow geese, white ibis) or sand hill cranes. Mostly those who report their sightings have first gone to our web page “Identification” section to convince themselves that they have made a correct identification.

During the past year we have received about 130 reports of whooping crane sightings. About 100 reports involved birds from the Aransas/Wood Buffalo (Western) flock. These reports came from persons in 7 central states and 2 Canadian provinces. And about 30 were sightings of cranes from the Operation Migration (Eastern) program. These reports came from 12 eastern states. If a report seems questionable, we discuss the observations with those who made the report. We believe that about 90 percent of the citizen reports are accurate.

The information received is useful in monitoring the migration of the cranes and determining the locations of some of the individuals at a point in time. Of course some of the cranes are counted more than once because they move often during migration.

An added benefit from the citizen spotters is that some of them send us interesting photos and videos of their observations. We recently received an interesting video and some unusual photos from one of those wonderful people who report their observations of whooping cranes to us. I requested and received permission from Cindy P….. to share with you her video and photos of whooping cranes on her property in Georgia. Her email description of her experience follows:

“Hi Chester,

Of course you may use any of the photos/audio that I shared with you for your website.

On December 17, 2012 at about 7:30 am, one pair of cranes arrived near our 3 acre pond. They grazed and walked about the property and within the next hour another pair of cranes appeared. I grabbed my camera and lenses along with my iphone and headed towards the pond. The four birds casually walked around the pond nibbling here and there. They walked all the way up towards the pine trees where I was able to photograph them using a telephoto lens. I was careful not to get too close to them (you can see in the audio/video how far away they were) so that I wouldn’t scare them off. They continued calling and browsing around for a couple of hours. I was ecstatic!”

“The next two days, the cranes came in and stayed for about thirty minutes before they flew due south. I have to say that they were absolutely gorgeous and I only wish I could have gotten closer. I took a great photo of them flying away. I live about 2 hours from St. Marks, Florida. I think these birds belonged to the flock that migrates that way each year. Hope you enjoy the pictures as much as I did making them. Merry Christmas to all….

Cindy P…. GA

To observe Cindy’s video click on the following: https://www.dropbox.com/s/hei3j65ty422v5k/WhoopCranesCalling.MOV

Several of Cindy’s photos are pasted below. Enjoy.

Being very catious. 12-17-2012

Migrating on south. 12-17-2012

MORE PHOTOS, READ ON:

Now, you can enjoy more whooper photos from more of our citizen reporters by clicking on the fol;lowing link: https://whoopingcrane.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/Whooper-photos-8-for-web-article-11-29-124.pdf

Whooping Cranes from Despair to Hope to Progress

December 23, 2012*************History Briefs compiled by Whooping Crane Conservation Association************

The recorded history of whooping cranes has ranged from beliefs that the birds would become extinct to efforts to restore the flock. Whooping Crane Conservation Association member Pam Bates has researched the literature and come across some interesting material. Some of Pam’s findings are posted here for your interest:

Despair: The following is from the Gutenburg Project and dated 1913.

OUR VANISHING WILD LIFE ITS EXTERMINATION AND PRESERVATION BY WILLIAM T. HORNADAY, Sc.D. Page 19. “The Whooping Crane. —This splendid bird will almost certainly be the next North American species to be totally exterminated. It is the only new world rival of the numerous large and showy cranes of the old world; for the sandhill crane is not in the same class as the white, black and blue giants of Asia. We will part from our stately Grus americanus with profound sorrow, for on this continent we ne’er shall see his like again. The well-nigh total disappearance of this species has been brought close home to us by the fact that there are less than half a dozen individuals alive in captivity, while in a wild state the bird is so rare as to be quite unobtainable. For example, for nearly five years an English [Page 19] gentlemen has been offering $1,000 for a pair, and the most enterprising bird collector in America has been quite unable to fill the order. So far as our information extends, the last living specimen captured was taken six or seven years ago. The last wild birds seen and reported were observed by Ernest Thompson Seton, who saw five below Fort McMurray, Saskatchewan, October 16th, 1907, and by John F. Ferry, who saw

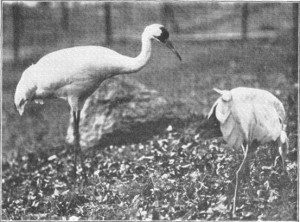

one at Big Quill Lake, Saskatchewan, in June, 1909. The range of this species once covered the eastern two-thirds of the continent of North America. It extended from the Atlantic coast to the Rocky Mountains, and from Great Bear Lake to Florida and Texas. Eastward of the Mississippi it has for twenty years been totally extinct, and the last specimens taken alive were found in Kansas and Nebraska. Photo was taken at “WHOOPING CRANES IN THE ZOOLOGICAL PARK ”

Hope: Two articles written by John O’Reilly in 1954 and 1955 issues of “Sports Illustrated” describe the extraordinary efforts of individuals, conservation organizations and government agencies to protect and manage the endangered whooping cranes. These two articles are posted below:

The surviving remnant of the great race of whooping cranes, hardly more than two dozen birds, will be “escorted” this fall from Canada to Texas. That is, they will be escorted insofar as it is possible for human beings to escort wild creatures which fly high and come to rest in lonely places. But, elusive though they may be, these huge white birds with the black wingtips will be followed on their route by thousands of well-wishers.

SPORTS ILLUSTRATED

Here Comes The Cranes, September 20, 1954

by John O”Reilly

The Survivors of America’s tallest birds will be “escorted” south

In advance of their coming a campaign is being conducted to alert the human population along the migration route of the cranes. As was the case last fall, radio stations will broadcast appeals to report the birds but not molest them. Their trip will be announced by newspapers. Sportsmen’s clubs and civic organizations have helped spread the word. Thousands of post cards bearing the facts and a picture of a whooper have been mailed to persons living along the flight lane.

All this is part of the international effort to help America’s tallest bird in its struggle for existence.

ONLY 26 ARE LEFT

When the birds migrated last spring there were 26 whooping cranes left—in the entire population of the species. Grus americana doesn’t occur in other parts of the world and they have been studied so thoroughly that the chance of even a single bird being discovered outside this group is highly improbable.

Two of the cranes, found crippled by gunshot, are now captives in a New Orleans zoo. The rest winter on the wide marshes and prairies of the 47,000-acre Arkansas Federal Wildlife Refuge on the Texas coast, 40 miles from Corpus Christi. There they live singly and in family groups, each family occupying a territory of some 500 acres from which other cranes are driven. Without the use of a blind it is difficult to get within half a mile of them. On a trip to the refuge I jeeped and stalked the prairies for days before I got a close view of the cranes. When a pair finally flew right over me I was told that I was luckier than most.

The exact location of the nesting grounds of the remaining whoopers has not been found. This summer a scientist hovering in a helicopter over the wild country south of Canada’s Great Slave Lake looked down and spotted four whooping cranes, three adults and a young one. His find was the best evidence so far of the general location of their breeding grounds.

The whooping crane once inhabited the central part of the continent from the Arctic Coast to central Mexico. It demanded plenty of space in which to live and rear its young, and when it stood at full height to utter its challenging buglelike call, it was almost six feet tall. But as the prairies were tamed and planted, the whooping cranes dwindled steadily.

PROJECT FOR SALVATION

Now the Fish and Wildlife Service, the Canadian Wildlife Service and the National Audubon Society are partners in a project designed to save the whooping crane from extinction. Numerous state agencies and private groups are cooperating. One of the prime workers on the project is Robert P. Allen, research ornithologist of the National Audubon Society. Allen devoted three years to an intensive study of the cranes, hoping to find a way to halt their decline.

During that time he lived with the birds on the lonely Texas marshes in winter. In early spring he took off by plane in advance of their migration and intercepted them along the Platte River in Nebraska. He traced their migration route through Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, the Dakotas and into Saskatchewan where they disappeared into Canada’s north country. He flew thousands of miles in the far north in a vain search for their nesting grounds.

People often ask how on earth the cranes know enough to go right to the refuge to spend the winter. The answer is that the presence of the whooping cranes there is historic and was one of the main reasons why the refuge was established in 1937.

As a result of Allen’s recommendations, numerous steps have been taken to aid the cranes. One of the main objectives has been to find the nesting grounds and learn whether there are any factors there which are limiting the increase. Canada has announced that when the nesting area is found it will be declared an inviolate sanctuary. Plans are now being made for a systematic search of the area next summer.

Each fall the refuge men are waiting eagerly as the cranes come back in little groups. By early December they are all in and the refuge men make an exact count by flying over them in small planes. In recent years the flock has returned with an average of four young birds. But usually a few of the parents are lost, some from being shot, and others from unknown causes. Sometimes the population fluctuates perilously. The gain or loss of a single bird is vital to the survival of the race.

Last year there was a gain. Twenty-one whoopers took off for the North in the spring and in the fall all 21 returned, bringing three gawky offspring with them. This fall more eyes than ever will be on the alert in the country’s most unusual bird-watching program.

SPORTS ILLUSTRATED

Whoop for Cranes – November 21, 1955 by John O’Reilly

Scientists who searched arduously and long for the nests of the all-but-extinct whooping crane rejoiced last week: its young are on the increase. Among birds, the all-but-extinct whooping crane is most symbolic of the mighty sweep of wilderness that once was America. Tall, wary and aloof, the whooping crane demands plenty of living space. It proclaims its utter freedom with a far-reaching, buglelike call. It regards the intrusions of man with an imperious look in its cold, yellow eyes. Although but a remnant of a once-great race, Grus americana seems imbued with a special urge to survive.

These are some of the reasons why the news of the return of 20 adult whooping cranes with a bonanza of eight young has just been greeted with such national exuberance. Last spring 21 whoopers left their wintering area on the Texas coast for their breeding grounds in northern Canada. By last Monday all except one adult were back in Texas. This bird may be lost or it still may be on the way. Sometimes the last migrants don’t get back until the first week in December.

A CAUSE FOR REJOICING

The appearance of eight young birds this year is cause for rejoicing among followers of the cranes both in the United States and Canada. The eight youngsters represent the largest crop since wildlife experts first started counting the remaining cranes 17 years ago. The largest previous number was seven young in 1939.

Anxiety over the migrating whoopers mounted steadily during the past two months as they made their 2,400-mile trip. Julian Howard, manager of the 47,000-acre Aransas National Wildlife Refuge near Austwell, Texas, has been swamped with demands for information on the returning whooper families. Never has the welfare of a migrating band of birds been of such concern to so many.

During the summer, workers on Project Whooping Crane, the international effort to keep the big birds flying, discovered the long-sought nesting ground of the last of the whoopers. As a result, it was known that the cranes had hatched at least six young.

Last summer, just as interest in the whoopers was reaching its height, the United States Air Force announced plans for establishing a photoflash bombing range within a mile of part of the birds’ wintering grounds. The National Audubon Society and local Audubon societies all over the country sent protests. More protests came from the National Parks Association, the United States Fish and Wildlife Service, the National Wildlife Federation, the American Nature Association and individuals who had helped in the struggle to save the cranes. Then the Canadian government made a verbal inquiry to the State Department. Last month the Air Force announced that its proposal to establish the bombing range had been withdrawn.

Old records show that whooping cranes once nested on the great prairies of the West and ranged over most of the country. Gradually they gave way before the plow and the gun, disappearing as their nesting grounds were settled and turned into wheat lands.

As long ago as 1923 some wildlife writers had declared the whooping crane extinct. The “last” nest had been found in Saskatchewan in 1922, and the young bird was taken from it, stuffed and placed in a museum. The existence of the wintering group on the Texas coast was known only to a few and it was their presence that led to the establishment, at that spot, of the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge. The big fight to save the whoopers started when Project Whooping Crane was set up 10 years ago.

The closest human associate of the whoopers since then has been Robert P. Allen, a square-built, black-haired Pennsylvanian. As research ornithologist of the National Audubon Society and leader in Project Whooping Crane, he had studied the cranes on their wintering grounds but his attempts to find their nesting sites in the far north had been fruitless. But, as he and others continued their work, public interest increased steadily.

The cause of the whooping crane became of such widespread interest that thousands of persons were on the lookout for them. Then in June 1954 some whoopers were spotted from a plane in Canada’s Wood Buffalo National Park, a wilderness area of 17,300 square miles, most of which is never visited by anybody, tourists or otherwise.

This knowledge led the international partners in Project Whooping Crane—the Canadian Wildlife Service, the’ U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Audubon Society—to launch an all-out effort to find the nests. Their aim was to discover whether anything or anybody was molesting the birds as they reared their young.

Allen was ready to start north to lead the expedition when William A. Fuller, biologist of the Canadian Wildlife Service, became the first man to see a wild whooper’s nest since that “last” nest was reported 33 years ago. Fuller was flying in the wild country along the Sass River on May 18 with Edward Wellien and Wesley Newcomb of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service when he spotted a pair of whoopers and a nest. On the same flight two more nests were seen.

This news spurred the expedition to action. Next to the actual finding of the nests the most important thing was to reach the area on the ground; to learn what, if any, were the dangers to the cranes; to study their nesting habitat and collect samples of their food. Allen hurried north and was met at Fort Smith, an outpost on the Slave River, by Raymond Stewart of the Canadian Wildlife Service and Robert E. Stewart, biologist of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Fort Smith is the jumping-off place for prospectors in the uranium rush. Men come and go and low conversations about uranium strikes are carried on in corners. So, as the three outfitted for their expedition, they were greeted with knowing smiles and sly smirks when they said they were heading into the bush to look for birds.

It was chilly on the morning of May 23 when the expedition set out down the mighty Slave River, which winds northwest to Great Slave Lake. At a great bend in the river, 44 miles from Fort Smith, they unloaded their supplies, cooked a meal and headed into the spruce forest. The Indian packers, two of them carrying the canoe, were strung out behind them. Nine hours later the three scientists said good by to the Indians and made their first camp on the shore of Long Slough.

As they moved down the slough the next morning in their overloaded canoe, the country around them was feeling the first touch of spring. Cattails were just beginning to show green. Canvasbacks, goldeneyes, buffleheads and other waterfowl were all about them. To the west they caught occasional glimpses of buffalo herds, with a spring crop of reddish-brown calves. They were still in high spirits when they made another portage, pitching their second camp on the banks of the Little Buffalo River. They moved up the Little Buffalo, still feeling fine. Turning into the Sass River, they rounded a bend to encounter their first trouble. It was a log jam, not of lumber logs but of trees and snags. They soon realized that the Sass was just one log jam after another, a fact that had not been apparent during their aerial survey.

They were sitting on the bank of the river, returning the stares of solemn buffalo and wondering what to do next, when they learned from their radio that they were believed lost and had become the objects of a search. The Northwest Mounted Police and park officials had been alerted. Unable to send out messages on their radio, they decided to strike for Fort Resolution on Great Slave Lake, where word of their safety could be sent out. After a turbulent trip down the Little Buffalo, they persuaded a Chipewyan Indian to carry a message across the frozen expanse of Great Slave Lake to Fort Resolution. Three days later Pat Carey, veteran bush pilot, dropped into the river mouth in his plane and took them back to Fort Smith. They were back where they had started.

A TRY BY HELICOPTER

Disappointment over their failure was forgotten on learning they could get the services of a helicopter which had been working north of Great Slave Lake. The helicopter transported them and their gear but, blown off course by a strong cross wind, the pilot became confused and dropped them 20 miles from where they thought they were landing. They didn’t realize this dismal fact until they had fought their way on foot for three days through swamps and sloughs.

Now they were really lost, and to make matters worse mosquitoes had emerged in millions, augmented by black flies, deer flies and a superdreadnaught called the bulldog fly. Their only relief from the clouds of insects came at night when they shut up their tent, killed the mosquitoes that were waiting inside and went to sleep.

At last, admitting they were licked, they put their canoe in the nearest river and started downstream. It turned out to be the Sass, the river of log jams. This time they cut their way through or portaged around 42 log jams, using the ax as much as the paddle. Reaching the Little Buffalo River, they went downstream and made the long portage back to the Slave River where a boat took them once more back to Fort Smith.

All told, they had been in the mosquito-infested woods for a month and hadn’t reached the home of the cranes. They had called the whole thing a failure and were ready to pull out when they learned another helicopter was available. Bob Stewart went back to Washington but Ray Stewart and Bob Allen prepared their gear for a third assault of the vast swamps.

This helicopter dropped them in the right spot and, as before, they started scouring the area on foot. Several days later Allen and Stewart emerged from a thicket to see a flash of white ahead of them. Slipping up, they came upon an adult whooping crane, drawn up to its full height of five and a half feet, silent and alert. Nearby was another. The two birds separated, finally moving out of sight. It was not until later that they learned this pair was hiding two offspring from them.

The goal had been reached. For 10 days the scientists studied the nesting habitat of the cranes. They collected specimens of frogs, fish, snails and other animal life which form the summer diet of the cranes. They also collected plant samples and made notes on everything that might have a bearing on the life of the whoopers.

Their work done, the helicopter ferried them out to the Slave River and they came up the river through the arctic twilight to Fort Smith in an outboard-driven skiff. Several days later I joined Bob Allen and Bill Fuller on a final aerial survey of the nesting area. As we moved over this watery world the scientists spotted two big, white birds. George Dannemann, our pilot, circled down to where we could tell they were whooping cranes. As the plane banked in a tight circle, we all saw not just the one, but two rusty-brown youngsters, two feet tall and standing between their white parents.

The scientists could restrain themselves no longer but began letting out whoops that would have done credit to the birds themselves. “Two young,” shouted Allen, and we all yelled in joy at just about the rarest sight that the bird world can offer in North America.

We saw two more fledglings on that flight and the scientists were jubilant. They and the thousands of others in the United States and Canada who are pulling for the whoopers know the cranes can never be brought back to their former numbers. But they also know that if Grus americana should disappear altogether it would mean the loss of something truly representative of the North American continent, for whooping cranes are nowhere else to be found.———End of O’Reilly article.

Voices from the Past: A 1954 recording of whooping cranes at Aransas. Pam Bates explains, “The Macaulay Library has 12 different whooping crane recordings but this one was my favorite because it talks about 1954 being the first year that they had 3 young whoopers that migrated with their parents from Canada. The whooping Crane population at Aransas was 24 that winter.”

Pam Bates advises, “The first speaker is Arthur Allen, a renowned ornithologist and who the Arthur A Allen Award is named after. Julian Howard, the second person to speak and mentions the annual count for 24 was the manager of Aransas at the time. Click on the link and follow:

ML: ML Audio 2739: Whooping Crane macaulaylibrary.org Finally, to hear the interesting Whooping Crane calls click on:

Unison (334kb wave)

Present: John O’Reilly was correct when he wrote in 1955 that “They and the thousands of others in the United States and Canada who are pulling for the whoopers know the cranes can never be brought back to their former numbers. But they also know that if Grus americana should disappear altogether it would mean the loss of something truly representative of the North American continent, for whooping cranes are nowhere else to be found. ”

Thank goodness that some of our government agencies and private conservation organizations continued to work to restore the whooping crane flock. The Whooping Crane Conservation Association has focused on this objective for over half a century. Very slowly during the past 57 years the flock has increased to approximately 300 in 2012. That’s progress by any measure.

Lobstick Whooper Remains A Mystery

December 21, 2012Editor’s Note: During April 2012 a whooping crane was murdered in the vicinity of Miller, South Dakota. At the time there was speculation that the dead crane was one of the famous Lobstick pair. The speculation continues. Captain Tommy Moore operates a tour boat in the vicinity of Aransas National Wildlife Refuge and believes he knows the Lobstick pair is alive. I contacted Tom Stehn retired Whooping Crane Coordinator to inquire. Luckily, Tom was going out the next day on Captain Moore’s boat and wrote me the following report. Chester McConnell, Whooping Crane Conservation Association, Web Administrator.

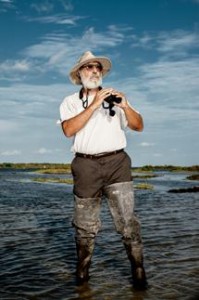

by Tom Stehn, Retired Whooping Crane Coordinator

On December 19th, I rode the whooping crane tour boat named the Black Skimmer to help with the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge’s Audubon Christmas Bird Count. Our group counted over 9,300 birds of 77 different species, but I didn’t see the bird I wanted to see most. The Lobstick whooping crane pair was not on its territory! We did spot 35 other whooping cranes, but I missed seeing what might be the oldest known aged whooping crane in the flock.

The Lobstick male was banded in 1978 as a 3-month-old chick in Canada’s Wood Buffalo National Park. After pairing up and successfully raising a chick in 1982, the Lobsticks continued their prolific breeding to become one of the most productive pairs in the flock. They have brought 17 chicks to Aransas in 31 years of nesting, and twice pulled off raising two chicks. Unfortunately, they have not made it to Aransas with a chick for the last three winters. The Lobstick male would now be 34, assuming he is still alive. His bands have fallen off, but voice printing multiple years ago of the male’s unison call had shown the same bird was present.

The pair continues to nest on Lobstick Creek just outside of Wood Buffalo National Park and defend the same territory on Aransas. They are often the first pair the whooping crane tour boats see. In the 2008-09 winter, the Lobstick male had difficulty flying for a spell, and the following winter we weren’t sure if he was present as the pair roamed more and was seemingly absent on several flights and boat trips. However, Captain Tommy Moore to this day continues to sight a crane pair on the Lobstick territory with a very large male that sometimes approaches the tour boat that could be Lobstick. Tommy thinks Lobstick is still alive. I don’t know for sure, but I’d like to think that 34-year-old old codger is still patrolling its Aransas territory as it keeps a glaring eye out for blue crabs and other cranes foolish enough to intrude on his territory. I didn’t see him the other day, but the refuge had recently done a prescribed burn, and I bet Lobstick had been on that upland area looking for roasted acorns. Other species of cranes have been known to live in captivity for over 80 years, so don’t count old Lobstick out.

Whooping Crane Conservation Association…working to conserve Whooping Cranes

December 16, 2012by Chester McConnell and Jim Lewis, WCCA

The Whooping Crane is the symbol of conservation in North America. Due to excellent cooperation between the United States and Canada, this endangered species is recovering from the brink of extinction. Their population increased from 16 individuals in 1941 to 588 wild and captive birds in September 2012. The name “Whooper” probably

came from the loud, single-note call they make when disturbed. The adult is 5 feet tall, the tallest bird in North America. When the wings are extended they are 7 feet from tip to tip. They are graceful flyers, elegant walkers, and picturesque dancers. Adults are a beautiful snowy white with black outer wing feathers visible when the wings are extended. The top of the head is red with a black cheek and back of neck, yellow eyes, and gray-black feet and legs.

Soft down covering the cute baby chicks is buff-brown. At about 40-days-of-age, cinnamon-brown feathers emerge. When they are one-year-old they have their white adult plumage.

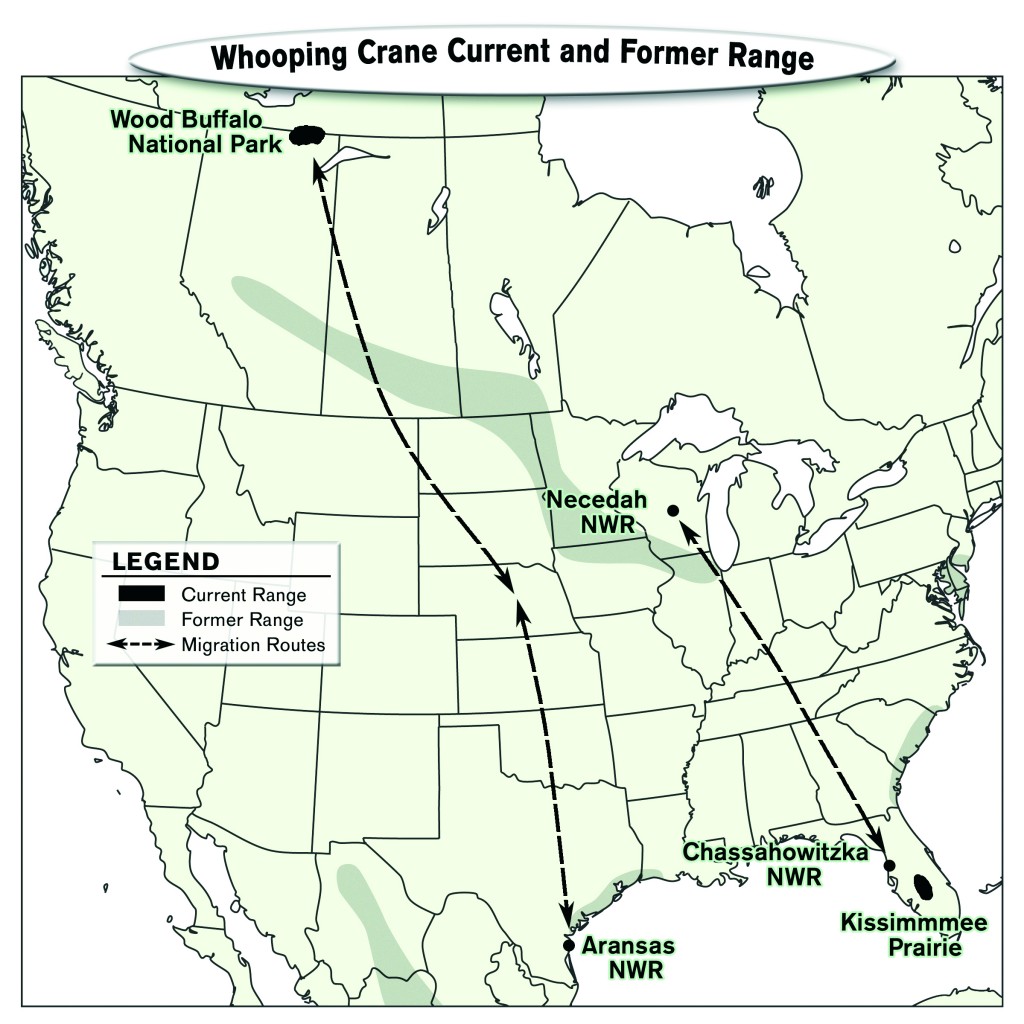

Despite progress in increasing the numbers of these birds, only one population maintains its numbers by rearing chicks in the wild. This flock now contains about 300 birds that nest in Wood Buffalo National Park, in the Northwest Territory of Canada. They migrate to the Gulf Coast of Texas on Aransas National Wildlife Refuge and bordering private land where they spend the winter. It is on their wintering ground where they are especially vulnerable. A hurricane could destroy their habitat and kill birds, or an oil spill could destroy their foods. Less abrupt, but equally dangerous, is diversion of river waters that flow into the crane’s habitat. This fresh water is being used upstream for agriculture and for human uses in cities. The steadily diminishing flow into the Gulf of Mexico is making the area less productive for Whooping Crane foods. They need these foods to remain healthy, and to fatten for strength on their 2,500-mile migration and for producing young when they arrive in Canada where winter is just ending.

Whooping Cranes were once more abundant in the 1800s, nesting in Illinois, Iowa, the Dakotas, and Minnesota northward through the prairie provinces of Canada, Alberta, and the Northwest Territory. Drainage and clearing and of areas for farming destroyed their habitat, and hunting reduced their numbers. The only wild population that survived by the 1940s was the isolated one nesting in Northwest Territory. In March-April these cranes fly from Texas across the Great Plains and Saskatchewan to reach their nesting area.

They begin pairing when 2 or 3 years old. Courtship involves dancing together and a duet called the Unison Call. Whooping Cranes mate for life. Females begin producing eggs at age 4 and generally produce two eggs each year. Usually only one chick survives. The pair returns to the same area each spring and chases other cranes from their nesting area that is called a “territory”. It may include a square mile or a larger area. Chasing other cranes away ensures there will be enough food for them and their chick. At night they stand in shallow water where they are safer from danger.

They build a nest in a shallow wetland, often on a shallow-water island. The large nest contains plants that grow in the water (sedges, bulrush, and cattail) and may measure 4 feet across and 8 to 18 inches high. The parents take turns keeping the eggs warm and they hatch in about 30 days. The two eggs are laid one to two days apart so one chick emerges before the other. They can walk and swim short distances within a few hours after hatching and may leave the nest when a day old. The chicks grow rapidly. They are called “colts” because they have long legs and seem to gallop when they run. In summer, Whooping Cranes eat minnows, frogs, insects, plant tubers, crayfish, snails, mice, voles, and other baby birds. They are good fliers by the time they are 80 days of age. In September-October they retrace their migration pathway to escape winter snows and reach the warm Texas coast. During migration they stop periodically to rest and feed on barley and wheat seeds that have fallen to the ground when farmers harvested their fields.

In Texas they live in shallow marshes, bays, and tidal flats. They return to the same area each winter and defend their “territory” by chasing away other cranes. The territory may contain 200 to 300 acres. Winter foods are primarily blue crabs and soft-shelled clams but include shrimp, eels, snakes, cranberries, minnows, crayfish, acorns, and roots.

An individual bird may live as long as 25 years. But, Whooping Cranes face many dangers in the wild. Coyotes, wolves, bobcats, and golden eagles kill adult cranes. Bears, ravens, and crows eat eggs and mink eat crane chicks. When they are flying in storms or poor light they sometimes crash into power lines. And they die of several types of diseases.

In addition to the single self-sustaining population there are birds in captivity at seven locations and three other wild populations began as experiments to try to ensure that Whooping Cranes survive in the wild. There are 183 cranes in captivity including 23 young. Most of the young are released into the wild as part of the three experiments. In the first experiment, begun in 1993, juvenile captive-reared cranes were released in the Kissimmee Prairie of central Florida. Additional young cranes were released there each year. This is a cooperative effort by U.S. and Canadian federal agencies, the state of Florida and the private sector, to start a population that does not face the hazards of migration. Cranes learn a migration route from their parents. These cranes were raised in captivity so they did not learn to migrate. There were 87 cranes in this flock in 2003 including 7 adult pairs that successfully raised 3 young to flight age. Only 20 remain in 2012.

In 1997, Kent Clegg was the first individual to teach captive-reared Whooping Cranes to fly and follow a small aircraft. He led them in an 800-mile migration in the western United States. His technique was then used in the second experiment beginning in 200l to establish a population that nests in Wisconsin and migrates to western Florida. U.S. and Canadian federal agencies, provincial and state governments, Operation Migration, Inc., and other private sector groups are cooperating in this experiment. This flock now contains 104 cranes and others will be added in future years. The annual releases will stop when the two experimental populations produce enough young to maintain their numbers. Another non-migratory flock with 20 whooping cranes was established in Louisiana in 2011.

HOW YOU CAN HELP

You can help the endangered Whooping Crane recover its numbers so it can survive as a species. Join the Whooping Crane Conservation Association (WCCA) by clicking on: https://whoopingcrane.com/membership/ The WCCA is a nonprofit organization and your donations are tax deductible. The Association helps purchase habitat, fund research and management projects that aid Whooping Cranes and assists in educating the public about the dangers to this beautiful bird. As part of your membership, you will receive a handsome newsletter twice a year. The newsletter provides the latest information on status of the various populations, recovery progress, and other items of interest. ell others about the dangers to this bird and what is being done to benefit them.

WCCA’s web page at www.whoopingcrane.com includes current information, interesting facts and a coloring book for children.

Stehn Frustrated With New Whooper Count Method

December 6, 2012MY OPINION ON THE CURRENT WHOOPING CRANE COUNT METHODS

BY: Tom Stehn

Retired Whooping Crane Coordinator

Aransas Pass, TX 78336

The whooping cranes are back at Aransas, and the Refuge has started their winter whooping crane counts. After I retired in the fall of 2011, count methods were changed from the complete census done for the past 61 years to a survey method using hierarchical distance sampling. I was told this was done for policy reasons, and that there were now too many whooping cranes to count them all. The latter statement is untrue; I successfully counted the cranes for 29 winters, including a peak of 282 whooping cranes, and feel a complete census will work with a flock size of at least 500. It may be that on some future date, it will be appropriate to sample the population rather than count all individuals, but I do not believe that date has yet arrived.

The new survey methods employ fixed transects flown at 1,000 meter intervals over four hours, whereas the census transects I used averaged ~400 meters wide and flights lasted approximately six hours. It is incomprehensible how the new survey method that finds fewer cranes is considered better than an actual census. To me, the more cranes you actually locate, the more you are going to learn. Why settle for an “estimate” when you have the opportunity to count nearly every individual each time you fly?

For the first winter since the refuge was established in 1937, no peak flock size was obtained in the 2011-2012 winter using the new distance sampling methods. Yes, the cranes were more dispersed that winter due to minimal food resources at Aransas, and the Service had difficulty finding approved aircraft to conduct the flights. Even given these difficulties, I would have come up with a peak population estimate using my old census methodology. Last winter, the new distance sampling methodology estimated 254 plus or minus 62 whooping cranes in the survey area. No one knew if the flock had increased or decreased in size from the previous year. This degree of uncertainty is simply unacceptable and useless for recovery management purposes. I believe the census methods I employed had no more than a 2% error. I knew I was not off by much since the results were so consistent from week to week. The number of adult pairs on the wintering grounds always agreed closely with the number of nesting pairs found the following summer in Canada. I averaged finding 95% of the cranes on every flight, and multiple flights over the winter season allowed me to put together the jigsaw puzzle of the flock composition (adults, subadults, juveniles, territory locations, mortality, habitat use, etc). The new survey methods do not attempt to locate territories or detect mortality, two actions recommended in the Recovery Plan.

Because the new survey methods are unproven and stakeholders are skeptical, I believe it would be prudent to continue to use the old census method while experimenting with the new method. Only when the new method is shown to be better should it be employed as the only survey methodology. I have written a letter to the Director of the USFWS and to the Director of Region II asking that they insure the flock gets censused this December before it is too late to obtain a peak count. If you agree with me, perhaps you might write a letter.

Whooping cranes are too valuable and too endangered not to count them annually to monitor how the flock is doing and how they are being impacted by numerous threats (sea level rise, housing developments, long-term decline of blue crabs, drought, invasion of black mangrove, power line and wind tower construction in the flyway, habitat loss, etc). For many, the whooping crane is considered the flagship species of the Endangered Species program. Because of this high level of interest and scrutiny, an accurate count is of great interest, both nationally and internationally. We owe it to the American people, our Canadian partners, and other conservation partners to provide them with the level of accurate information to which they have become accustomed.

Although happily retired, I’m frustrated by the people involved with the count insisting that their new methods are “better” when results to date prove they are not. One can’t expect me to be objective, but on the other hand, I have as much knowledge as anybody of counting whooping cranes. I urge the USFWS to utilize transects no more than 500 meters apart which will enable them to find a much higher percentage of the crane flock. Why not do a census using 500 meter transects one day and conduct a distance sampling survey at 1000 meter transects the next day to compare methods? Biologists can then decide if distance sampling is a useful tool. But at five feet tall and with nothing to hide behind, it is not hard to find nearly every whooping crane from the air. Come on Fish and Wildlife Service; use the count methods that are the most effective.

CELEBRATE WHOOPERS RETURN TO ARANSAS

December 1, 2012by Chester McConnell, Whooping Crane Conservation Association

All but a few whooping cranes have made it back to Aransas Refuge, Texas from their nesting area in Wood Buffalo National Park, Canada. The other birds are expected to arrive at their winter home on Aransas soon. Some are taking a respite at several locations, including Granger Lake, about 150 miles north of the refuge.

Sixteen whooping cranes migrating south towards Aransas National Wildlife Refuge, Texas. Photo by: Mike Umscheid

(For posters of the photo click: http://www.mikeumscheidphotography.com/title.php?n=SixteenWhooping&m=poster

The 2,400 mile migration trek from Wood Buffalo to Aransas has taken place for thousands of years and is cause for celebration by us humans. We celebrate because whooping cranes are increasing in numbers after facing extinction in the 1940s – 50s. The total flock had reached a low of only 15 birds when we began serious efforts to rescue them from their dismal plight.

While the precise number of whoopers in the Aransas-Wood Buffalo flock is not known, estimates are that there are about 300+ today. The Whooping Crane Conservation Association reported in August that, during the 2012 nesting season, the flock produced 34 juvenile birds, including two sets of twins.

Increases in the whooping crane population is fantastic news for humans who are attempting mightily to right a wrong and now protect this last group of naturally migrating whooping cranes in existence. For many years we destroyed much of their habitat and killed them for food and feathers without compassion. Now, reformed human attitudes have resulted in promising plans and extraordinary efforts to restore the whooper flock to secure numbers.

According to the new U.S. Whooping Crane Coordinator Dr. Wade Harrell, Aransas Refuge biologists conducted the first whooping crane aerial survey of the season November 28, 2012, and the second survey is being flown on the 29th. Data analysis from the surveys is ongoing and several additional flights are scheduled to occur prior to December 17th. Most of the GPS radio-tagged birds have arrived, according to a release issued by Aransas National Wildlife Refuge officials. An updated preliminary estimate of the current size of the whooper population is expected after the data analysis is completed in mid-December. (See news release at: http://www.fws.gov/nwrs/threecolumn.aspx?id=2147503362 )

Based on the first survey flight, the cranes appear to be evenly distributed on the Refuge from Lamar to south of Port O’Connor. Also according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, marsh conditions on Aransas look good, and whoopers are feeding on the abundant wolfberry crop and the plentiful blue crabs. Currently the habitat conditions on the refuge look good.

* For copies of whooping crane poster click : http://www.mikeumscheidphotography.com/title.php?n=SixteenWhooping&m=poster