Author Archive

TAP Urges Attendance at Whooping Crane Count Meeting

October 22, 2012by Ron Outen, Regional Director, The Aransas Project

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service will hold a second Public Meeting at Aransas National Wildlife Refuge on Wednesday, October 24th. The public is urged to attend to learn about the Service’s new method to count whooping cranes.

It was truly gratifying to see the great outpouring of support for and interest in the whooping cranes from the Rockport community at the October 4th presentation by USFWS on the new distance sampling methodology being used at Aransas National Wildlife Refuge. The questions asked by the audience demonstrated again that the Aransas-Rockport area is one of the most knowledgeable and engaged communities anywhere, especially when it comes to the whooping crane.

We hope that folks who attended that first public presentation, as well as others who may have been unable to attend, will attend a second public presentation being offered by USFWS:

Wednesday, October 24, 2012

6 to 8 p.m.

Aransas National Wildlife Refuge

(six miles south of Austwell on Farm-to-Market Road 2040)

Because USFWS issued its Aransas-Wood Buffalo Whooping Crane Abundance Survey (2011 – 2012) only one day before the October 4 briefing, this is a great opportunity to ask further questions of Aransas Refuge staff after having had more opportunity to review the report, or simply to ask questions that you didn’t get a chance to ask last time.

Video of October 4th presentation Available Online:

The Aransas Project has posted a video documenting the two-hour public presentation by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service on the distance sampling methodology in use at the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge during the last wintering season. The presentation was held on Oct. 4, 2012 in Fulton, and includes the formal presentation as well as questions from the audience following the presentation. While there was a great crowd on hand with many well-informed questions, we know that many people were not able to attend. We hope that this video documentation is helpful to the whooping crane community around the world in staying informed on this critical issue.

As you can see in the next article below, the defendants in TAP’s litigation have sought to supplement the record with USFWS’ Oct. 3 report, which is critical of Stehn’s methodology. We think that you will find that the tone of the presentation captured in the video differs significantly in its characterization of Stehn’s work from that of the written report released by USFWS one day prior to that public meeting. It also gives you a great sense of the strong level of public engagement on this issue.

Defendants Seek to File USFWS Report in TAP Litigation:

Judge Will Not Admit Without Full Evidentiary Hearing to Probe Credibility

As reported recently by Matthew Tresaugue of the Houston Chronicle, TAP supporters should also be aware that the State of Texas, the Guadalupe-Blanco River Authority and other defendants have sought to introduce USFWS’ Oct. 3 report into evidence more than 9 months after the close of the trial in TAP’s lawsuit under the Endangered Species Act. The Oct. 3 report criticizes the previous census method and introduces USFWS’ new statistical modeling method of estimating peak flock size. The previous census method was used since 1982 by USFWS’s own prior Crane Coordinator, Tom Stehn. Stehn’s work led the recovery and survey of this species until he retired in September 2011.

The federal district judge presiding over the case has indicated that the report will not be admitted into evidence without a full evidentiary hearing at which the authors of the report from USFWS are available would be required to testify. Read more about this development.

Crane Migration Back to Texas Coast Underway:

All of us who love the cranes are excited that the annual migration back to the Texas coast from the summer nesting grounds in Canada is underway. In a blog post entitled, “Whooping Cranes Migrating South to Texas” https://whoopingcrane.com/whooping-cranes-migrating-south-to-texas/ , Chester McConnell of the The Whooping Crane Conservation Association reports that the cranes had a successful summer nesting season. Check out Chester’s post to learn more about estimates on the number of cranes expected to arrive at the Refuge.

The Victoria Advocate Editorial Board also issued an editorial on the return of the cranes, encouraging residents to visit the Refuge to see the cranes and noting significantly that:

In a way, the cranes are protecting us as well. Their protected status limits the amount of water that can be taken from the rivers feeding into the refuge in order to maintain the correct balance in the estuary that houses the cranes’ major food source. While this may be an inconvenience for some area industries, it ultimately protects our waters from being siphoned away from our area, keeping it here to meet the needs of area residents and wildlife.

While all of us in the Coastal Bend need no reminder of the critical link between our well-being and that of the cranes, it is encouraging to see this message from the Advocate’s Editorial Board.

Thanks so much for your continued support. Please feel free to forward this on to a friend.

Whooping Cranes Migrating South to Texas

October 17, 2012by Chester McConnell, Whooping Crane Conservation Association

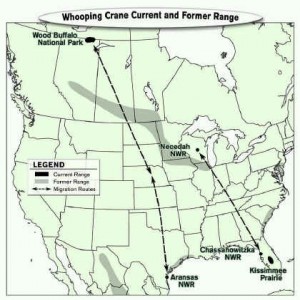

They are on their way! The whooping cranes have departed from their Wood Buffalo National Park nesting grounds in Canada and are migrating towards Aransas National Wildlife Refuge on the Texas coast. For many thousands of years the endangered cranes have made this annual 2,400 mile migration. It is one of nature’s wonders.

The Whooping Crane Conservation Association has received dozens of reports of whoopers from birders in Alberta and Saskatchewan, Canada and North Dakota, Nebraska and Texas. Approximately 300 whoopers are expected to arrive at Aransas Refuge by late November. Hopefully the thirty-four (34) juvenile cranes that were observed on the Canadian nesting grounds will all make it to Texas with the adult birds.

During the nesting period in May sixty six (66) whooping crane nests were discovered by the Canadian Wildlife Service. Three months later in August, an additional three (3) family groups were identified indicating that there were at least sixty-nine (69) nesting attempts during the 2012 nesting season. In early August, just prior to fledging, thirty-four (34) young including two (2) sets of twins were observed on the breeding grounds. Ten of the young whooping cranes were marked with leg bands and satellite transmitters so details about their migration can be learned.

Whoopers usually follow a migratory path through Saskatchewan, North and South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma and Texas. In central Texas they fly near cities such as Wichita Falls, Fort Worth, Waco, Austin, and Victoria. During migration they often pause overnight to use wetlands for roosting and agricultural fields

They nearly migrate in small groups of less than 4 to 6 birds, but they may be seen roosting and feeding with large flocks of the smaller sandhill crane. They are the tallest birds in North America, standing nearly five feet tall. They are solid white in color except for black wing-tips that are visible only in flight. They fly with necks and legs outstretched. Hunters are urged to learn to identify whooping cranes to avoid mistaking them for some other birds.To help identify whooping cranes, please click on the following link: https://whoopingcrane.com/whooper-identification/

Since beginning their slow recovery from a low of 16 birds in the 1940s, whoopers have, with few exceptions, always wintered on the Texas coast on and near Aransas National Wildlife Refuge. However, in the winter of 2011-12, several groups of whooping cranes expanded their wintering areas to include more coastal areas and even some inland sites in Central Texas, Kansas and Nebraska—patterns that surprised crane biologists. Texas has initiated the “Texas Whooper Watch” program that asks the public to help us discover more about where whooping cranes stop in migration and to be ready to learn more about these potential new wintering areas. The Whooping Crane Conservation Association and Texas will share information collected about whoopers from birders to improve our knowledge about the birds.

The Whooping Crane Conservation Association is hopeful for a much better winter season on Aransas Refuge. As most whooping crane interests know, last winter on the refuge was abnormal in several respects, including severe drought conditions and poor food availability. Some of the cranes spent some or all of the winter away from Aransas making accurate counts of the birds impossible. During the past several months, the Aransas area has received more rain and habitat conditions are improved. Blue crab numbers have rebounded along the Aransas Refuge coast and the returning whooping cranes will, at least, start out with a good food supply. Hopefully the wolfberry crop will improve and be another source of food.

Nesting Success Good For Whooping Cranes In 2012

October 8, 2012by Chester McConnell, Whooping Crane Conservation Association

Whooping crane nesting success on Wood Buffalo National Park, Canada during 2012 was considered good but slightly down from previous years. This is good news after the poor winter season on Aransas National Wildlife Refuge in Texas.

Sixty six (66) whooping crane nests were discovered in May by the CanadianWildlife Service. Three months later in August, an additional three (3) family groups were identified indicating that there were at least sixty-nine (69) nesting attempts during the2012 nesting season. In early August, just prior to fledging, thirty-four (34) young were observed on the breeding grounds. Two (2) sets of twins were observed. Ten of the young whooping cranes were marked with leg bands and satellite transmitters.

Martha Tacha, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service reports that: “The whooping cranes began moving down into staging areas in Saskatchewan last month; a week ago about half of the GPS-marked cranes were in Saskatchewan. There are currently 30 whooping cranes carrying working GPS transmitters, and likely a hand-full of marked cranes with colored leg bands from 1978 to 1988 marking effort. As of this morning (Oct.5), there were no GPS-marked cranes in the United States except for one young whooper in Burke County, in extreme northwest North Dakota (this bird was also observed independently by biologists on the ground on and after September 22, 2012). However, I have also received confirmed, probable, and several unconfirmed reports of whooping cranes observed as far south as southcentral North Dakota, so apparently at least one or two whooping cranes without GPS transmitters have moved farther into the northern reaches of the U.S. Flyway.” Citizen birders have also reported to the Whooping Crane Conservation Association of their observation of whooping cranes in Saskatchewan and North Dakota.

The Whooping Crane Conservation Association is hopeful for a much better winter season on Aransas Refuge. As most whooping crane interests know, last winter on the refuge was abnormal in several respects, including severe drought conditions and poor food availability. Some of the cranes spent some or all of the winter away from Aransas making accurate counts of the birds impossible. During the past several months, the Aransas area has received more rain and habitat conditions are improved. Blue crab numbers have rebounded along the Aransas Refuge coast and the returning whooping cranes will, at least, start out with a good food supply. Hopefully the wolfberry crop will improve and be another source of food.

The retirement of Tom Stehn last year resulted in a change from a direct count method to a transect-based survey of the greater Aransas NWR area to estimate the number of whooping cranes wintering there. Therefore, the official estimate of 254 whooping cranes wintering at Aransas last winter is not comparable to previous years’ estimates of flock size. There was much optimism that a record three hundred (300) whoopers would be counted on Aransas Refuge in 2012, but due to the unusual movements of the cranes and the new census method, the accurate number will never be known. Hopefully, this winter will be more typical in terms of crane distribution and Aransas Refuge biologists will be successful in making an accurate count.

Citizens Want Accurate and Timely Whooping Crane Information

October 6, 2012Community Expresses Clear Desire for Accurate and Timely Whooping Crane Data

by Ron Outen, Regional Director, The Aransas Project

A public meeting held by the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge staff in Fulton to provide information about changes in tracking and reporting the numbers of endangered whooping cranes wintering at the Refuge was well-attended by the community as well as by local elected officials.

The Oct. 4 meeting followed on the heels of USFWS’s Oct. 3 release of a report that they titled,, “Aransas-Wood Buffalo Whooping Crane Abundance Survey (2011-2012).” In addition to providing information on the new distance sampling method employed for the first time during the winter of 2011-2012, the report was critical of the census methods employed for nearly 30 years by retired Refuge Biologist and International Whooping Crane Recovery Coordinator Tom Stehn, and even before that dating back to the 1950’s.

The presentation was led by current Refuge Biologist Brad Strobel, who did an admirable job of laying out the history of the way in which the cranes had been counted at the Refuge, as well as sharing information on the development of the new distance sampling method being used to provide a point estimate of the crane population on the Refuge last winter, which he described as a “work in progress.”

In contrast to USFWS’ written report, Strobel had abundant praise for Stehn’s work, and repeatedly noted that he wished he could “channel Tom Stehn” to arrive at precise counts. “If there was a way that I could channel Tom and do it the same way that Tom did it, believe me I would.” explained Refuge Biologist Brad Strobel. Other Refuge staff also in attendance included Refuge Manager Dan Alonso and newly named Whooping Crane Recovery Coordinator Dr. Wade Harrell.

As soon as the Question and Answer period began, it was immediately clear how passionate, engaged and informed this community is about the whooping crane. A few highlights included:

Demand for Accurate Information on Number of Cranes to Continue: Community members frequently noted in their comments and question that they, and people all over the world, expected regular information on the number of cranes in the flock. As one audience member put it, “I need to know how many whooping cranes are here, how many of them die or disappear, and why.” There was extensive discussion of how far off the peak estimate of 254 cranes could be, and it was agreed that the variance could be as much as plus/minus 30 birds.

New Method Focuses Solely on Population, Not Mortality: Strobel acknowledged that the new method focuses solely on estimating population and does not measure mortality (which is unknown for the winter of 2011-2012), while also noting that “winter mortality is a critical metric.”

Need for Public Input: The audience was extremely interested in how the new distance sampling method had been developed, and in who had input in the creation of the protocol. Strobel indicated that he had developed the new protocol along with members of the USFWS regional staff, including himself, regional Biometrician Matt Butler and Regional Chief of Biosciences Grant Harris. While Refuge staff indicated that the new protocol would be peer-reviewed by experts only, the audience expressed the need for broader public review and comment.

Better and More Timely Communication: Nancy Brown, USFWS Public Outreach Specialist, who invited questions about communication to her at nancy_brown@fws.gov and indicated that USFWS was in the process of developing a new website to enable better communication, but in the meantime, the current website would continue to be updated at least every two weeks with information. Notices of upcoming meetings, as well as the presentation and FAQ sheet from last night’s meeting will be made available.

While it is clear that there remain a great number of questions to be examined with respect to the tracking and management of the flock, the meeting was a positive first step in creating a community dialogue on this important issue. The Refuge staff plans to do additional public meetings, with the next meeting to be held at the Refuge on October 24th. TAP will continue to keep you informed on this critical issue.

TAP Concerned About Whooping Crane Survey Methodology Changes

October 4, 2012by Ron Outen,

REGIONAL DIRECTOR, THE ARANSAS PROJECT

The Aransas Project (TAP) leaders announced their concerns about the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s proposed new whooping crane survey methodology. TAP is urging its members to attend a critical public meeting being hosted by the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge to address the changes being made in the survey methods used to count the endangered whooping cranes that winter at the Refuge. Beginning in the winter of 2011-2012, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS) altered its methodology for tracking how many cranes are in the flock and this will be the first public meeting providing any insight or explanation of their methods. In July 2012, TAP released our State of the Flock 2011-2012 report, documenting concerns with the methodology as well as how the flock fared in Winter 2011-2012.

TAP members are strongly encouraged to attend to remain informed on this critical issue:

Thursday, October 4, 2012

6 PM to 8 PM

Paws and Taws Convention Center

402 North Fulton Beach Road Fulton, TX 78358

According to a USFWS news release, the presentation “will investigate and define aerial survey methods used historically and currently to count the Aransas-Wood Buffalo flock of whooping cranes.” Refuge Biologist Brad Strobel will lead the presentation, and there will be a Q&A session following the presentation.

October 3, 2012: USFWS Posts Report

On October 3, the eve of their public meeting in Fulton, the USFWS has posted to their website a report that they titled,“Aransas-Wood Buffalo Whooping Crane Abundance Survey (2011-2012)”. The report states that its first objective is “to share information in a timely manner;” however, the report was promised by August and was posted October 3, one day in advance of the public meeting noted above.

The report primarily focuses on criticizing the previous census method and introducing their new statistical modeling method of estimating peak flock size. The previous census method was used since 1982 by USFWS’s own prior Crane Coordinator, Tom Stehn. Stehn’s work led the recovery and survey of this species until he retired in September 2011.

Given the timing of the release of this report, TAP’s review has identified, at a minimum, a number of issues of concern:

Territoriality: The report states that, “[the] assumption of territoriality is unnecessary and untenable given recent data.” This conclusion is stunning, and flies in the face of the established scientific literature, decades worth of banding data, and earlier GPS tracking data. This conclusion appears to be based solely on one year’s GPS tracking data that was collected in a year when the cranes were clearly dispersed due to severe drought.

The End of Crane Counting?: Because the new method is designed to statistically estimate only peak flock size, it appears that USFWS no longer intends to track or tell the public how many cranes are in the flock, or how many cranes die at Aransas in any given year.

Basis and Data for New Peak Count Unclear: In contrast to the previous method that clearly counted and reported the number of cranes, the new statistical style instead counts some cranes and then estimates the peak flock count, a number that is buried in pages of complex statistical lingo. Additionally, because USFWS does not share the underlying raw data, it is difficult to determine how a new peak flock estimate of 254 birds was derived.

These are only a few of the questions that are prompted by this report, and TAP is concerned that the report was not provided further in advance of this public meeting to allow full analysis by researchers and the public. We hope that USFWS will be able to shed additional light on the reasoning and conclusions reached in the report in light of the concerns expressed above.

Whooping Crane Program Concerns

September 29, 2012by Chester McConnell, Editor

As editor of the Whooping Crane Conservation Association web page, I am concerned about several issues associated with the Aransas/Wood Buffalo whooping crane flock. These issues include the: (1) lack of information available to the public related to the apparent decline in the population of the cranes from 279 cranes in 2010-2011 to 245 cranes in 2011-2012; (2) the proposed new statistical sampling method to monitor the whooping crane population; and (3) the increasing difficulty to obtain information from government agencies that manage the flock.

I recognize that there have been several major changes in management personnel in both the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Canadian Wildlife Service. Replacing long-term, experienced employees in complex programs normally results in some glitches. And then, the unusual weather and related food availability during the past year has seemingly caused migration abnormalities. I try to take these into consideration. Yet, when we cannot get any information on the whooping crane reproduction circumstances on Wood Buffalo habitats, I cannot fathom that. Good golly, the cranes are already beginning their migration south to Aransas National Wildlife Refuge, Texas and we have not heard a word about hatching success and related information during the past spring and summer. Why?

A major factor in the success of any program such as the whooping crane endangered species project is strong public support. Officials involved in the program today would be wise to review the history concerning how the Aransas/Wood Buffalo flock project evolved. In summary it was largely due to strong public pressure and long-term support from early U.S. and Canadian leaders in the Whooping Crane Conservation Association. We want to continue supporting the program but we need information from government project personnel to do so.

I visited the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge this week and discussed some of these issues with a couple of officials. The refuge is being managed well and the new observation tower is a tremendous improvement. They invited me to attend the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service meeting in Fulton, Texas October 4, 2012 to participate in a briefing on crane survey methodology changes. Hopefully, we will at least get some answers and improved understanding about what is going on during this session. I urge you to attend.

UPDATE: The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service just released (October 3, 2012) it’s report, Aransas-Wood Buffalo Whooping Crane Abundance Survey (2011-2012)”. We will be studying the report but have included it here so you, our viewers, will have the most current information.

The following news release provides details about the meeting.

News Release: Updates from The Aransas Project SEP 28, 2012

The Aransas Project (TAP) Members Urged to Attend Briefing on Crane Survey Methodology Changes

TAP members are urged to attend a critical public meeting being hosted by the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge to address the changes being made in the survey methods used to count the endangered whooping cranes that winter at the Refuge. Beginning in the winter of 2011-2012, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS) altered its methodology for tracking how many cranes are in the flock and this will be the first public meeting providing any insight or explanation of their methods. TAP members are strongly encouraged to attend to remain informed on this critical issue.

Thursday, October 4, 2012

6 PM to 8 PM

Paws and Taws Convention Center

402 North Fulton Beach Road, Fulton, TX 78358

According to a USFWS news release, the presentation “will investigate and define aerial survey methods used historically and currently to count the Aransas-Wood Buffalo flock of whooping cranes.” Refuge Biologist Brad Strobel will lead the presentation, and there will be a Q&A session following the presentation.

State of the Flock Report: TAP Concerns Persist

In July 2012, TAP released our State of the Flock 2011-2012 report, highlighting the following concerns:

• USFWS Methodology Faulted

Concerns regarding the new statistical sampling method used by USFWS, including reported concerns by former Refuge Biologist and Whooping Crane Recovery Coordinator Tom Stehn;

• Whooping Crane Flock Numbers Plunge during Winter 2011-2012

A stunning decline in the population of the cranes, even under USFWS’ statistical sampling method, from 279 cranes in 2010-2011 to 245 cranes in 2011-2012; and

• Tracking Data Suggests Unprecedented Crane Mortality

Evidence gathered from a smaller population of cranes tracked by GPS that suggests an unprecedented crane mortality of 9.6% in this monitored subgroup of birds that exceeds the previous high mortality rate of 8.5% experienced during the winter of 2008-2009.

USFWS Yet to Deliver Final Report

In their June 14, 2012 report, USFWS indicated they would issue a final “State of the Cranes” report by August 2012 summarizing the significant events that occurred during the 2011-12 whooping crane season. To date, USFWS has not released this annual state of the flock report.

TAP remains concerned about the absence of this report along with the changes in the survey methodology being used by USFWS to monitor the health of the Aransas-Wood Buffalo flock, and invites TAP members to come to the meeting to remain informed on this issue and ask questions of the Refuge staff.

USFWS Appoints New Crane Coordinator, Dr. Wade Harrell

In related news, USFWS recently issued a news release announcing the appointment of Dr. Wade Harrell as the new Whooping Crane Recovery Coordinator. According to the release, Wade will be part of the Region 2 Recovery staff in Albuquerque, but he will be based at Aransas National Wildlife Refuge. TAP welcomes Dr. Harrell in his important new role, and we hope that TAP members will have the opportunity to meet Dr. Harrell at the upcoming meeting.

We hope that you will join us.

Thanks so much for your continued support. Please feel free to forward this on to a friend.

Ron Outen

REGIONAL DIRECTOR, THE ARANSAS PROJECT

Young Whooping Crane In Capture Project Dies

September 3, 2012 |

|

Young whooping cranes, 31 in all, have been banded with transmitters for three summers in their summer Wood Buffalo National Park habitat. (Photo: Courtesy of Parks Canada)

|

A juvenile whooping crane has died, possibly from a self-inflicted wound suffered trying to escape capture in Wood Buffalo National Park. The bird was to be banded as part of a program attaching radio transmitters to juvenile cranes. The carcass has been shipped to the Canadian Cooperative Wildlife Centre in Saskatoon for autopsy.

“We don’t know the cause of death. The crane was injured. It may have happened as part of the capture process,” Stuart McMillan, Wood Buffalo National Park manager of Resource Conservation told The Journal.

Crews land in a helicopter and try to round up the young birds, which naturally run away. McMillan said cranes are known to scratch themselves while running.

The bird was seen to be injured after it was captured for the banding process. A veterinarian is part of the capture crew and the young bird was examined immediately, treated with an antibiotic and released. It returned to its parents and things seemed normal. Some time later, the signal from the transmitter stopped moving. On investigation, the bird was found dead.

“It is certainly disappointing. We didn’t want to have a result like this. We want to find out what happened to prevent it from happening again,” said McMillan.

He said if the cause of death is from the capture process they will study it and make changes to procedures to minimize the risk of it happening again.

The banding exercise, called “telemetry,” is a joint Canada-US project. Thirty one juvenile cranes have been outfitted with transmitters over the last three years without incident.

Migration routes, habitat sought during migration, food sources and threats cranes face are just some of the information the project hopes to gather. The data is still preliminary, and it is too early to draw conclusions.

It is known that whooping cranes often stop in the same places year after year as they come and go annually between Aransas Wildlife Refuge in Texas and Wood Buffalo National Park in the NWT. In some places where they are known to stop each year, people gather to watch for them. It is hoped that public awareness can be raised once more is learned about where and when they stop.

One thing being investigated is the impact of power lines. Dead cranes have been found in the vicinity of power lines but no one knows why. Some speculate lines should be marked along the migration route and that new lines planned in those locations be erected at different sites. One benefit of the radio transmitters is that a dead bird can be found right away.

“When a crane dies it is best to look at an intact carcass to determine the cause of death, not one decomposed or torn apart by scavengers. If banded with a transmitter which stops moving, we can go look for the bird right away,” said McMillan.

This winter, adult birds will also be captured and banded at the Aransas Wildlife Refuge.

Tracking Whooping Cranes – Telemetry Update

September 1, 2012Article courtesy of Crane Trust

The Crane Trust continues to gain momentum in their efforts to contribute to conservation and the preservation of the whooping crane and other migratory birds. The Whooping Crane Conservation Association applauds their work and believes viewers of our web page will appreciate reading one of their recent reports. The following is an excerpt from Crane Trust’s July-August newsletter.

The Crane Trust is one of five research groups involved in a remote-tracking study of whooping cranes in the world’s only self-sustaining flock—the Aransas-Wood Buffalo population, comprised of fewer than 300 cranes. Findings from the study will help the Trust and its partners better understand the ecology and threats to whooping cranes on their wintering grounds, breeding grounds, and their 2,500-mile migration route through the Central Flyway. Twice each year, the Whooping Crane Tracking Partnership publishes an update on its progress and findings. For the two latest reports on progress and findings, click downloads below. Above photo courtesy of Michael Sloat.

2011 Fall Report DOWNLOAD (2011 summer breeding/fall migration)

2012 Spring Report DOWNLOAD (2011-2012 winter season/spring migration)

You can download the two most recent reports at the end of this summary. Of note, the study’s research team has improved its methods of trapping and continues to catch and mark young and adult whooping cranes with GPS transmitters on both breeding and wintering grounds. For each bird, the solar-powered transmitters provide up to 4 signals a day for the life of the device (3-5 years). In the winter of 2011, that amounted to more than 11,000 locations for tracking and analysis. To read the entire article click on following link: http://www.cranetrust.org/newsletter/july-august-2012/tracking-whooping-cranes-in-space-and-time%E2%80%94telemetry-update/

Journey North Whooping Crane Info

August 25, 2012Journey North produces one of the most interesting web pages that I am aware of. It is a prime educational tool for teachers and appeals to nature interests of all ages. Recently Journey North posted some very interesting information concerning Whooping Cranes and the Seasons, The Annual Cycle of the Whooping Crane. We wanted our viewers to be aware of Journey North’s information and we pasted their post in hopes it will be easier for you to open. We invite you to click on the “blue links” below to observe some excellent photography and associated information about whooping cranes.

Chester McConnell, Web Page Editor, Whooping Crane Conservation Association

Whooping Cranes and the Seasons Whooping Cranes and the SeasonsThe Annual Cycle of the Whooping Crane More Slideshows |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Whooping Crane Man

July 23, 2012by Michael Berryhill , a Texas Monthly article, August 2012

No one knows more about whooping cranes than Tom Stehn, who studied and cared for them for three decades. Then he retired—only to discover that the magnificent and endangered birds needed him more than ever.

Early last December, Tom Stehn was enjoying his retirement in Aransas Pass, soaking in his hot tub after a morning of windsurfing, when the phone rang. He grimaced for a moment but hopped out of the water naked to see who was bothering him. A U.S. marshal was calling from his car, which was parked in Stehn’s driveway. A federal judge in Corpus Christi wanted him to testify about the deaths of 23 whooping cranes he’d reported during the winter of 2008 to 2009, two years before he had retired. The marshal asked if Stehn could come to court immediately. “All right,” he said, “but give me a minute to put on my clothes.”Stehn knew what the case was about. A longtime biologist for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, he had served as its whooping crane coordinator for over a decade. No one had more hands-on experience with the birds, which are among the most endangered in North America. He had flown on countless aerial surveys to identify the whooping cranes’ winter territories in the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge, studied their habitat, measured the salinity of their marshes, celebrated their return each year, nurtured their sick, and, when he could, recovered their dead. In the winter of 2008 an emaciated juvenile had died in his arms.

Over the years, Stehn had watched the flock grow from 71 to nearly 300 birds. But he determined that during the drought of 2008 and 2009, 8.5 percent of the wintering flock and nearly 45 percent of the first-year juveniles had died. The following year, coastal tourism businesses, environmentalists, and the O’Connor family of Victoria, who owns tens of thousands of acres near the Guadalupe River, formed a nonprofit group called the Aransas Project and sued the state. The organization claimed that, under the Endangered Species Act, the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) was responsible for the deaths of the cranes because it had failed to allow enough freshwater to flow from the Guadalupe River into San Antonio Bay, which adjoins the wildlife refuge.

The State of Texas, led by the Guadalupe–Blanco River Authority (GBRA), countered that the lawsuit was based on pure speculation. Of the 23 birds that Stehn had reported dead, only 4 carcasses had been recovered. How could he prove the others had died? And even if they had, how could the environmentalists know that the deaths resulted from a lack of freshwater? Witnesses for the state contended that computer models proved the whooping cranes could survive perfectly well with very little freshwater. They even claimed that because of a special gland, whooping cranes might not need to drink freshwater at all.

The case has exposed a long-simmering battle between the two sides. Although state law directs the TCEQ to plan for freshwater inflows to keep Texas bays healthy and productive, environmentalists have been complaining for years that the agency has failed to live up to its responsibilities. In 2003, for example, a group of environmentalists had applied for water rights to protect wildlife in San Antonio Bay, and the TCEQ denied the request. The GBRA, in particular, has a great deal at stake. Its priorities are cities, farmers, and industry, and there are plans for several new power plants, including a proposed nuclear facility, to be built in the region. If the plaintiffs win, those projects could be put on hold.

Both parties had visited Stehn’s old office and obtained copies of his annual reports, and both had tried to recruit him as a paid expert witness. Though the Department of the Interior typically prohibits its biologists from testifying as expert witnesses, Stehn was inclined to stay out of the trial anyway. He had been concerned about the management of the Guadalupe River for years, and he worried that the state’s lawyers would try to destroy his life’s work to win the suit. U.S. district judge Janis Jack decided that Stehn’s testimony was essential, however, and she ordered each side to pay half of his $200-an-hour fee. “That’s good Christmas money,” the judge told him.

Since this was a bench trial, the case hinged primarily on whether Jack believed Stehn’s testimony. It was as if he were the only eyewitness at a murder trial and the victims were his children. Still, his presence did provide a bit of levity. Because his last name rhymes with the birds’ name, the judge would laugh when lawyers on both sides addressed him, in slips of the tongue, as “Mr. Crane.”

“I know these cranes,” he told the court. “I’ve been watching some of the same ones since 1982. I hate to be—what’s the word?—anthropomorphic, but it’s almost like they’re my kids out there.”

Of the fifteen species of cranes in the world, Stehn explained, only the whooping crane is territorial about its winter grounds. Mated pairs, some with juveniles they have reared during the summer in Canada, stake out an average of 425 acres of coastal marsh along the peninsulas and barrier islands of San Antonio Bay. When these territories were first mapped, in the late forties, there were only fourteen. As the flock grew over the years, the birds claimed smaller pieces of marsh, and by the winter of 2008 to 2009, Stehn had identified seventy different territories. Because the birds always returned to the same place, Stehn believed his weekly aerial surveys would allow him to count every crane. (The Lobstick territory had been used by the same male crane for thirty years.) He finally concluded that the flock had grown to 270 birds, plus or minus 2 or 3 percent.

After Stehn explained his census methods, Jim Blackburn, a veteran environmental attorney from Houston who was leading the case for the Aransas Project, asked the kind of question that lawyers hate: one whose answer they’re not absolutely sure of. He needed to know how many cranes had died that winter. “Is twenty-three your number?” he asked.

Stehn took a long moment to think about his response. Blackburn felt his gut turning over, because this was the heart of the case. Stehn noticed a look of puzzlement, almost panic, in Blackburn’s face and then said, “If I had to pick a number, it would be higher than twenty-three.”

The dead included mated pairs that had not had offspring as well as pure-white parents with rusty juveniles. But Stehn had also been watching ninety subadults, who tended to move about the refuge. “They can be on the refuge one day, they can fly across the bay to San José [Island] the next day or the next hour . . . they can be singles,” Stehn testified. “So you can’t ever tell if a bird like that is missing. It’s very reasonable to assume that some of them died that are not in that twenty-three.”

As for the 23 Stehn was certain had died, he could identify each by territory and date. Because the deaths had occurred all across the refuge, he believed that drought was the culprit. “It was a high-mortality winter,” Stehn said, “and at that point, the food supply was not good. There were low numbers of crabs, and the wolfberry crop had not been good. And from my experience, that kind of screams out that trouble is brewing.”

The refuge staff started feeding the cranes shelled corn at thirteen stations on upland parts of the cranes’ winter grounds, but this created a different problem. The birds are safest from predators in the open marsh, but when they fly inland, they increase their chances of being attacked by bobcats and other predators. To follow up on Stehn’s testimony, the environmentalists needed to prove that the lack of freshwater inflows was also related to the deaths. Two Rice University professors presented data that linked low river inflows to high crane mortality.

The GBRA fought back with a $2.14 million study it had helped fund in 2002 called the San Antonio Guadalupe Estuarine System, or SAGES, to determine the effect of freshwater inflows on whooping cranes. The report, which was released in 2009, around the same time that Stehn had reported the deaths of the cranes, concluded, “None of the study results indicated that habitat conditions [at the refuge] are marginal for crane survival and well-being.” The SAGES scientists built a conceptual computer model that indicated there was plenty of food, regardless of conditions.

During the testimony, Jack freely interrupted lawyers and questioned witnesses. She wrote notes furiously and researched suspect statements. At the outset of the trial she cracked, “I just wanted to rule out the fact that those [missing cranes] could have gone to New Mexico or, you know, to Antigua for the holidays or something.” Most of her remarks were aimed at the defense. She often shut down lines of questioning that seemed tiresome with a terse phrase: “Got it.” During eight days of testimony, the state heard that a lot.

A defense witness who reviewed the necropsy of one of the four crane carcasses noted that the bird had a greenish discoloration of the leg, which he associated with gangrene. Jack was astounded. She was well aware that gangrene is typically associated with a blue or black discoloration, so she grilled him about other weaknesses in his testimony. “I’m sorry,” she told the courtroom. “I know I’m being difficult with him, but I have never heard a scientist say when he saw something green that he thought of gangrene. I can’t quite move beyond it.”

Jack was even harder on R. Douglas Slack, the Texas A&M professor who led the SAGES study. Slack’s researchers had concluded that insects, clams, snails, and acorns would provide enough nutrition for the cranes, basing their findings in part on eighty to ninety hours’ worth of sometimes fuzzy videos that recorded the feeding habits of the birds. Stehn had presented Texas Parks and Wildlife Department data that showed that the cranes’ favored food, blue crabs, declined during times of low river inflow.

Jack grew exasperated with the SAGES model and its failure to incorporate the diet and mortality data that Stehn had collected. Under her intense questioning, Slack conceded that the cranes probably did need freshwater inflows—even if the model said they didn’t.

“Okay,” Jack said. “I’m just telling you, you can’t create a model. You can’t create a multiplier based on no information, which is what you’ve done. You have done it on what you figure is a normal, walking-around bird without determining how much energy it takes to forage for this versus forage for that. All these different things are critical to the well-being of the whooping crane. Even I can figure that one out.”

Slack’s most embarrassing moment came when the judge pressed him about the cranes’ supraorbital salt gland, which the defense claimed made them immune to the high salinity that comes with drought.

“I’ll tell you,” Jack said, “when the report was filed, I said, ‘What is this, a natural desalinization plan?’ So I looked it up, and there wasn’t anybody that ever described any such thing on a whooping crane.”

At one point, Jack asked Slack, “Where did you get that?”

“I don’t know,” he replied.

“You just made it up?”

“Yeah, I just made it up.”

After eight days of testimony, Jack heard no final arguments but instead asked each side to file briefs. She has encouraged both sides to work toward a settlement while she reviews the testimony, but if they cannot reach an agreement, she could issue a verdict as early as this month. If Jack rules for the Aransas Project, she could order the state to negotiate a Habitat Conservation Plan, in which the state would apportion the cranes a share of freshwater from the Guadalupe River. Bill West, the general manager of the GBRA, said that such a ruling would overturn traditional Texas water rights that date back more than one hundred years and disrupt the economic growth of the middle coast of Texas. “There’s no question,” he said. “It’s a classic example of federal intervention into state water rights by use of the Endangered Species Act. The judge does not have the authority to interfere with state water rights.”

In the meantime, Stehn has returned to Aransas Pass and to windsurfing, soaking in his hot tub, and enjoying the peace and quiet. But he laments how his old job has changed. During last year’s record drought, the remains of three cranes were recovered, but the total number of deaths was difficult to determine. That’s because biologists now employ a technique known as distance sampling to estimate the size of the flock. The new method, which is widely used to determine the populations of rare and endangered wildlife, doesn’t count birds individually, as Stehn used to do. Instead biologists fly aerial surveys during a predetermined time frame, and the cranes that are identified are recorded as a percentage to determine the population. However, according to guidelines, the two observers in the plane are not allowed to tell each other if one sees a bird. Nor does the pilot return, as Stehn did, and fly over a particular area again and again to search for missing birds in specific territories.

Stehn always believed that the results of his census were 97 to 98 percent accurate. He has read that the new method for estimating the birds is only 85 percent accurate. He thinks that between thirty and forty cranes could have died last winter, but nobody knows for sure. Current surveys put the refuge’s population at 245 cranes. That represents a loss of 38 birds from Stehn’s final census in 2010 and 2011, though the U.S. Parks and Wildlife Service points out that it’s difficult to compare the numbers given the different methods of data collection and harsh drought conditions of the previous winter. “I think last year was a bad year,” Stehn said. “I’m frustrated that the refuge didn’t document that. They fell flat on their face.”

Stehn is concerned about more than the end of an annual count, though. He worries that invasive black mangrove and rising sea levels could wipe out the cranes’ marshes. Perhaps Stehn’s problem is that he stayed at the Aransas refuge too long, but after he arrived thirty years ago, he never left. Images of whooping cranes decorate his walls, his T-shirts, and his coffee mugs. Looking back at his career, he says, with a hint of wonder, “I just got enamored with cranes.”![]()