Author Archive

2011 Migration Begins

September 16, 2011Tom Stehn, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service biologist advised the Whooping Crane Conservation Association that a few of the radioed whooping cranes have recently left Wood Buffalo nesting grounds in Canada. Some have reached Saskatchewan.

So the southward migration is underway as per the usual time frame starting in mid-September.

Stehn stated, It’ll be several weeks before we expect whoopers in the U.S. And soon they will be back on their wintering grounds at Aransas National Wildlife Refuge in Texas. We are expecting a record number of whoopers to arrive in Texas.

Tom Stehn Retires

September 10, 2011

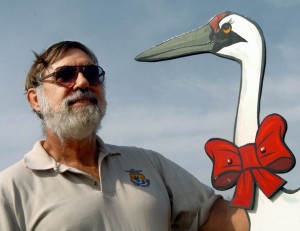

Tom and Lipstick

Tom Stehn, Whooping Crane Coordinator, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service will be retiring on September 30, 2011. Tom has been an outstanding Coordinator for the Whooping Crane program. He has always worked with all interests including the Whooping Crane Conservation Association. Always at the ready to answer emails and telephone calls and serve as a speaker at our programs, Tom has served us and all others exceptionally well. Tom is from the old school and knows and appreciates the role of private conservation groups. We could ask for no better. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service could ask for no better. We will miss Tom but wish him the best in retirement.

I asked Tom to give us a final message…

“My news from Aransas is that I am going to retire September 30th! I feel so lucky to have been able to have such a rewarding career and work with such wonderful people. After 29 years at Aransas doing crane work and 32+ years federal service, it’s time for a change, whatever the future may bring. We’ll stay in Aransas Pass on the Texas coast since my wife will continue her solo practise as a family physician. I’ll be windsurfing daily and planning trips to the mountains to do more hiking. It is likely that an acting whooping crane coordinator will be appointed to carry on the program. Refuge Biologist Brad Strobel will lead the whooping crane monitoring program at Aransas.”

Tom Stehn.

Whooping Crane Recovery Activities

September 1, 2011October, 2010 – August, 2011

by Tom Stehn

Whooping Crane Coordinator

U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Highlights

The Aransas-Wood Buffalo population (AWBP) of whooping cranes rebounded from 263 in the spring of 2010 to 279 in the spring, 2011. With approximately 37 chicks fledged from a record 75 nests in August 2011, the flock size should reach record levels of around 300 this fall. Threats to the flock in Texas including land development, reduced freshwater inflows, the spread of black mangrove, the long-term decline of blue crab populations, sea level rise, land subsidence, and wind farm and power line construction in the migration corridor all continue to be important issues.

Twelve whooping crane juveniles were captured in Wood Buffalo National Park (WBNP) in August 2011, bringing the total number of radioed birds to 23. Crews visited migration stopover sites to gather habitat use data. This project is being carried out by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) with partners including The Crane Trust, Canadian Wildlife Service (CWS), U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) and others. It is funded by the Platte River Recovery Implementation Program, The Crane Trust, and the Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center. The tracking is the first done on the AWBP in 25 years and is a top research priority of the Whooping Crane Recovery Team! Since the 1950s, 525 AWBP whooping cranes have died with only 50 carcasses recovered, and approximate cause of death was determined in only 38 instances. It is imperative that we learn more about whooping crane mortality.

Based on opportunistic sightings, the Cooperative Whooping Crane Tracking Project documented 79 confirmed sightings of whooping cranes in the U.S. Central Flyway during fall, 2010 and 49 sightings in spring, 2011.

Ten captive-raised whooping cranes were released in February, 2011 at White Lake, Louisiana where a non-migratory flock had resided up until 1950. Seven of the birds were alive after the first seven months of the project.

Production in the wild from reintroduced flocks in 2011 was again very disappointing with no chicks fledged in Florida or Wisconsin. Incubation behavior in Florida and nest abandonment in Wisconsin continued to be the focus of research. Data collected so far in Wisconsin indicates that swarms of black flies play some kind of role in a majority of nest abandonments.

The captive flocks had a good production season in 2011. Approximately 17 chicks were raised in captivity for the non-migratory flock in Louisiana, and 18 chicks are headed for Wisconsin (10 for the ultralight project at the White River marshes, and 8 for Direct Autumn Release at Horicon National Wildlife Refuge). Approximately four chicks of high genetic value were held back for the captive flocks.

Including juvenile cranes expected to be reintroduced this fall, flock sizes are estimated at 278 for the AWBP, 115 for the WI to FL flock, 20 nonmigratory birds in Florida, and 24 in Louisiana. With 162 cranes in captivity, the total of whooping cranes is 599.

Nesting Research Conducted on Florida Cranes

August 30, 2011 We continue to study the whooping cranes of the Florida resident flock. The flock contains 20 birds, 16 of which are paired. This spring we employed camera “traps” near nests of whooping and sandhill cranes in order to learn more about nesting issues. Camera traps, or trail-cameras as they are sometimes called, are cameras triggered by heat differential and motion. At night they use infrared “flash” to illuminate the photos. Wildlife cannot see the flash so it does not affect their behavior.

We continue to study the whooping cranes of the Florida resident flock. The flock contains 20 birds, 16 of which are paired. This spring we employed camera “traps” near nests of whooping and sandhill cranes in order to learn more about nesting issues. Camera traps, or trail-cameras as they are sometimes called, are cameras triggered by heat differential and motion. At night they use infrared “flash” to illuminate the photos. Wildlife cannot see the flash so it does not affect their behavior.

Most of our data so far are from sandhill crane nests and all results are preliminary. However, we are seeing some interesting results from the camera traps at nests. The cameras were useful for documenting 1) many occasions of visitors (representing disturbances or potential disturbances) to nests, 2) whether a nest was successful or not, 3) water levels at nests,and 4) behaviors of the birds at their nests. The following examples are presented in that order.

Camera traps successfullydocumented many disturbances or potential disturbances at nests. For one nest,the last image of the attending crane was when it flushed from the nest in the dark; and then a bobcat (Lynx rufus) walked by the nest.

While the nest was unattended, raccoons (Procyonlotor) came and scavenged the nest.

Raccoons were common near nests; at one nest they triggered the camera daily. Coyotes (Canis latrans) and an alligator (Alligator mississippiensis) also were photographed.

Sandhillcranes defended their nests from curious livestock, even when it meant dealing with an animal that weighed 200 times more than the crane.

Camera traps also successfully documented whether nests hatched. Camera placement in relation to the nests provided clear views of chicks when they hatched.

Also significant at this nest was the fact they were also incubating a data-logging egg that we had placed in their nest. The data recorded will provide a “known successful” recipe for incubation temperature.

Camera traps also documented water levels. This is important because too much water can flood nests and too little water will cause abandonment. One nest was unique in that the nest was constructed of mud and sticks on a natural rise in an otherwise open-water pond. Extremes in water level can be seen at this nest in the next picture.

Camera traps captured important bird behaviors. Last year we discovered from data-logging eggs that whooping cranes were sometimes leaving their nests unattended at night. This quarter we deployed the first-ever successful camera trap at a whooping crane nest.

Important was the documentation of the pair exchanging incubation duties in the dark.

Of the trailcam photos from sandhill nests we reviewed thus far there have been no obvious nest exchanges at night. This could be a fundamental behavioral difference between the 2 species that previously has been undescribed (but we’ll need data from more whooping crane nests before we can say that). Or, it could be a behavioral artifact of captive rearing for the whooping cranes. Whatever the reason, it would seem to add vulnerability to the eggs and potentially attract attention to the nests of whooping cranes.

We ended the 2011 nesting season with data from 22 sandhill crane nests and 7 whooping crane nests. The results are still preliminary, but it is evident that these new techniques for studying nest success are providing exciting and valuable information about crane reproduction. We plan to continue the study next year to get more data, especially from whooping crane nests. This work was funded in part by the U.S.Fish and Wildlife Service.

Marty Folk, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission.

Wind Farm Update

July 26, 2011An interesting twist on the wind farm story from the Star Tribune, Minneapolis, MN

Your comments needed…

July 21, 2011See earlier posts:

Vast wind energy proposal could kill endangered birds

Wind Farms and Whooping Cranes

Opportunity to provide your comments to:

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR, Fish and Wildlife Service concerning effects of wind turbines on Whooping Cranes.

Draft Environmental Impact Statement and Habitat Conservation Plan for Commercial Wind Energy Developments Within Nine States

AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, Interior.

ACTION: Notice of intent; announcement of public scoping meetings; request for comments.

———————————————————————–

SUMMARY: We, the Fish and Wildlife Service, as lead agency advise the public that we intend to prepare an environmental impact statement (EIS) on a proposed application, including a Habitat Conservation Plan (HCP), for an Incidental Take Permit (ITP) under the Endangered Species Act of 1973, as amended. The potential ITP would include federally listed and candidate species within portions of nine states (North Dakota, South Dakota, Montana, Colorado, Nebraska, Kansas, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Texas).

The activities covered by a potential ITP would include regional-level construction, operation, and maintenance associated with multiple commercial wind energy facilities. The planning partners are currently considering, for inclusion in the HCP, certain species listed as federally threatened or endangered, or having the potential to become listed during the life of the HCP, and having some likelihood of being taken by the applicant’s activities within the proposed permit area. The intended effect of this notice is to gather information from the public to develop and analyze the effects of the potential issuance of an ITP that would facilitate wind energy development within the planning area, while minimizing incidental take and mitigating the effects of any incidental take to the maximum extent practicable.

We provide this notice to (1) Describe the proposed action; (2) advise other Federal and state agencies, potentially affected tribal interests, and the public of our intent to prepare an EIS; (3) announce the initiation of a 90-day public scoping period; and (4) obtain suggestions and information on the scope of issues and possible alternatives to be included in the EIS.

Click on the following for the total Federal Register Announcement

Wind Farms and Whooping Cranes

July 21, 2011The development of wind farms is occurring at a rapid pace in the Central Flyway with many of the best wind sites located in the whooping crane migration corridor. Tom Stehn, Whooping Crane Coordinator, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) advised the Whooping Crane Conservation Association (WCCA) that multiple wind farms have already been built with more planned. Stehn stated, “It is important to analyze the potential impact of literally tens of thousands of wind turbines that may be placed in the whooping crane migration corridor in the coming years.

Current estimates are that 2,705 turbines are operational at 40 wind farms in the U. S. whooping crane migration corridor. The average wind development project consists of 57 turbines (data generated by the Great Plains Wind Energy Habitat Conservation Plan (HCP) in March, 2011).

The majority of wind farms do not require federal permits and thus there is no nexus for the companies to consult with USFWS under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). However, the projects must avoid “take” of endangered species under Section 9 of the ESA. USFWS’ Stehn advised that: “For the totality of wind energy development, there is a very definite issue of “take”. Wind farms have the potential to directly kill whooping cranes from the turbines themselves or associated power line development, or could result in “take” of hundreds of square miles of migration stopover habitat if whooping cranes tend to avoid wind farms.” The National Academy of Science Report in 2004 on Platte River endangered species confirmed unequivocally the threat to whooping cranes if migration habitat is lost.

Early on in discussions with wind companies, USFWS talked of two possible scenarios for offsetting anticipated impacts of wind farms. These were to set aside whooping crane migration stopover habitat in perpetuity to counter potential loss of habitat from wind farm construction, as well as to mark new power lines, as well as some existing power lines to offset the threat of whooping cranes colliding with a wind turbine or power lines built to support wind development.

According to Stehn: “At the urging of USFWS at meetings held in Denver and Houston as well as regular conference calls, 19 of the largest wind development companies joined together to work on endangered species issues throughout the whooping crane migration corridor in the U.S. With the support of the State of Oklahoma, the industry group received a grant of $1,080,990 to develop a landscape level, multi-species HCP that would include the lesser prairie chicken. The grant was awarded through the Cooperative Endangered Species Conservation Fund under the HCP Planning Assistance Program. The HCP will be designed to avoid and minimize impacts to endangered and threatened species associated with wind energy development.”

This multi-species HCP will be the first of its kind to involve alternative fuel sources while protecting endangered species. In a meeting in Tulsa, Oklahoma in November, 2010, four species were added to the HCP (Sprague’s pipit, mountain plover, piping plover and interior least tern), joining the whooping crane and lesser prairie chicken. An additional meeting was held in March, 2011 in Albuquerque. It does appear that this industry group will agree to have the wintering grounds of the whooping cranes as off- limits to wind energy development. However, projects in the migration corridor are currently being built and are not waiting for this HCP to be completed.

In 2010, monitoring for cranes was done at the Titan I wind facility in South Dakota. In the spring, a group of 5 whooping cranes spent 3 days approximately 2 miles from the project. The closest they were ever on the ground from a turbine was 1.2 miles. When they resumed migration, the nearest turbine was shut down in a very rapid response as the monitor called in that the cranes were flying. The cranes passed by that turbine at a distance of about one-half mile. In the fall, two groups of whooping cranes (2+1 and 2) flew within 0.5 and 0.3 miles from an operating turbine but did not seem to alter their flight behavior.

Research on sandhill cranes in west Texas done by Laura Navarrete of Texas Tech University documented two observed instances of cranes being killed by wind turbine blades. Although sandhill cranes definitely avoided wind farms, she also observed accommodation with cranes foraging right at the base of turbines. Research done by U.S. Geological Survey at Horicon NWR in Wisconsin also showed some avoidance by sandhill cranes from wind farms.

WCCA article based on communications with Tom Stehn, USFWS

Vast wind energy proposal could kill endangered birds

July 21, 2011By Laura Zuckerman

SALMON, Idaho (Reuters)| Thu Jul 14, 2011 6:13pm EDT

The Obama administration is evaluating a plan to allow a 200-mile corridor for wind energy development from Canada to the Gulf of Mexico that would allow for killing endangered whooping cranes.

The government’s environmental review will consider a permit sought by 19 energy developers that would permit turbines and transmission lines on non-federal lands in nine states from Montana to the Texas coast, overlapping with the migratory route of the cranes.

The permit from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service would allow the projects to “take” an unspecified number of endangered species. Under the Endangered Species Act, “take” is defined as killing or injuring an endangered species

The government can issue permits to kill or injure listed species with no penalties or risks of lawsuits to developers who agree to craft conservation plans. According to federal officials, the large scale of the review will help streamline the permitting process by lumping many projects into a single study.

The Obama Administration has been working to speed development of renewable energy projects by improving coordination among various state and federal agencies. Environmentalists, however, say the “fast track” process results in inadequate environmental reviews.

The Administration’s latest wind energy proposal raises concerns among wildlife advocates because the developments would overlap with habitat imperiled birds such as whooping cranes rely on, including the Central Flyway, a migratory path that cuts through North America’s midsection between the Arctic and the Tropics.

The leading cause of death for the nation’s last historic population of whooping cranes, which stand at 5 feet and have a wingspan of more than 7 feet, is overhead utility lines, the Fish and Wildlife Service said.

Conservationists say the Central Flyway’s population of 280 cranes — which make a refueling stop along Platte River in Nebraska along with tens of thousands of sandhill cranes and snow geese — would suffer with the loss of just a single adult breeding bird.

‘RAREST OF BIRDS’

“I can hardly imagine what the government is thinking. Whooping cranes are the rarest of all the cranes, the rarest of American birds,” said Paul Johnsgard, author of several books on the cranes and professor emeritus of ornithology at the University of Nebraska.

Fish & Wildlife Service Director Dan Ashe said wind energy is crucial to the nation’s future economic and environmental security, which is why the agency is paving the way for a renewable energy project with an undetermined number of wind turbines generating an unidentified amount of electricity along the 200-mile-wide corridor.

“We will do our part to facilitate development of wind energy resources, while ensuring that they are sited and designed in ways that minimize and avoid negative impacts to fish and wildlife,” he said in a statement.

Whooping cranes, North America’s tallest bird, once numbered in the tens of thousands before hunting and habitat loss caused their populations to plummet to 16 in the 1930s.

The cranes, which annually migrate thousands of miles from wintering grounds in coastal Texas to breeding and nesting areas in Alberta, Canada, were at the forefront of an emerging wildlife conservation movement in the 1960s that gave rise to a series of landmark laws aimed at preventing extinctions of rare and declining animals.

Whooping cranes were among the first creatures added to an early version of the Endangered Species Act in 1967.

Few other populations of whooping cranes exist in the United States, with an introduced flock in central Florida that does not migrate and a fledging group in Wisconsin that biologists have trained to fly to the winter refuge of Florida by following ultralight aircraft.

Attempts to establish crane populations elsewhere, including Idaho and Colorado, have failed.

Government scientists have not yet determined how many whooping cranes, other threatened and endangered birds and imperiled bats would be killed or otherwise harmed because of the wind project, said Amelia Orton-Palmer, conservation planner with the service.

“It’s so early in the process we won’t begin to speculate on what that might be,” she said.

Whooping Cranes Return to White Lake

July 15, 2011

Costumed caretakers process a bird at the release pen in Louisiana. Photo by Brac Salyers, LDWF

There are many success stories on species recovery associated with the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries (LDWF) and in February 2011 LDWF added one more. The department’s Coastal and Nongame Resources Division (CNR) moved forward with a whooping crane re-population project that will be as challenging as any previous effort.

“LDWF biologists have a proven track record for bringing back species from threatened or endangered status to robust population levels readily noticeable around the state,” said LDWF Secretary Robert Barham. “From the alligator and the brown pelican, to the bald eagle and the white-tailed deer, our citizens can see the results of years of tedious field work. The expertise and dedication that LDWF biologists bring to a long-term restoration plan is truly impressive.” For Louisianans, the sight of a whooping crane in the wild has been only a distant memory. The last record of the species in Louisiana dates back to 1950, when the last surviving whooping crane was removed from Vermilion Parish property that is now part of LDWF’s White Lake Wetlands Conservation Area (WLWCA).

The whooping crane is the most endangered crane species. Fifteen species of cranes occur throughout the world; only two of the 15 species, sandhill cranes (Grus canadensis) and whooping cranes (Grus americana) occur in North America. Today, sandhill cranes are prevalent, but whooping cranes are in great peril, having suffered severe population declines during the late 1800s and most of the 1900s. Due to these declines, whooping cranes were placed on the federal endangered species status list on March 11, 1967. The population slowly increased over the last 30 years with approximately 565 individual whoopers in North America as of Jan. 31, 2011.

Historically, both resident and migratory populations of whooping cranes were present in Louisiana through the early 1940s. The massive birds, with males growing to 5 feet tall at maturity, inhabited the marshes and ridges of the state’s southwest Chenier Coastal Plain, as well as the uplands of prairie terrace habitat to the north. According to Dr. Gay Gomez, professor of geography at McNeese State University and Louisiana whooping crane historian, “Records from the 1890s indicated ‘large numbers’ of both whooping cranes and sandhill cranes on wet prairies year round.”

The Louisiana whoopers are not the only cranes in the wild. A self-sustaining wild population of whooping cranes migrates between Wood Buffalo National Park in the Northwest Territories of Canada and Aransas National Wildlife Refuge in Texas. Like those in an eastern migratory population, the Aransas group remains vulnerable to extinction from continued loss of habitat and catastrophes, either natural or man-made. Multiple efforts are underway to reduce these risks and bring this magnificent bird further along its path to recovery. This includes increasing populations in the wild, ongoing efforts to establish a migratory population in the eastern United States and establishing a resident (non-migratory) population in Louisiana. The White Lake marshes and vast surrounding coastal marshes of southwest Louisiana was a positive factor in the decision making process that led to the experimental population approval.

The Louisiana crane population did not withstand the pressure of human encroachment, conversion of nesting habitat to agricultural acreage, hunting, and specimen collection, which also occurred across North America. Dr. Gomez’s research indicates “In May of 1939, biologist John Lynch reported 13 whooping cranes north of White Lake and that in August 1940, flood waters associated with a hurricane scattered the resident White Lake population of cranes and only six of the 13 cranes returned. By 1947, only one crane remained at White lake and in March of 1950, the last crane in Louisiana was captured and relocated to Aransas National Wildlife Refuge, Texas.”

Whooping cranes currently exist in three wild populations and within captive breeding populations. Captive breeding facilities are responsible for providing eggs that will eventually be released back into the wild. The 10 juvenile cranes relocated to White Lake on February 16 were raised at the Patuxent Wildlife Research Center in Laurel, Md. The eggs were hatched in May and June 2010 by birds in four locations including the Calgary Zoo in Alberta, Canada, Necedah National Wildlife Refuge in Necedah, WI. Audubon Species Survival Center in New Orleans and Patuxent facility. The young cranes were then flown to Jennings, La. and transported to the White Lake property.

The process preceding the cranes arrival, which involved project approval by the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), public meetings and a public comment period, spanned more than two years. “Without our cooperative partners, which includes USFWS, U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and International Crane Foundation (ICF), this project would not have come to fruition,” said LDWF-CNR Division Administrator Robert Love. “We will continue to work closely with this group for years to come.”

Acclimation pen. Photo by Michael Seymour, LDWF

Upon their arrival in February, the birds were placed in a small, netted acclimation pen within a larger 1.5-acre pen located at WLWCA. The birds remained in the netted acclimation pen for approximately one month to allow proper transition to their new locale and to allow researchers and biologists the opportunity to ensure all birds were healthy and well acclimated to their surroundings. The birds adjusted quickly and within 24 hours of their arrival, one individual was observed catching and eating a wild crawfish. In addition to wild caught food, the birds have been receiving supplemental pelletized food referred to as crane chow. While contained within the acclimation pen, each bird was fitted with unique leg band colors, a USFWS I.D. band and satellite transmitter. The bands and transmitters will allow biologists and researchers the opportunity to study and follow each bird through its lifespan.

The White Lake cranes were released from the netted acclimation pen on March 14. Biologists conduct daily monitoring activities and continued supplemental feeding activities. The birds can roam free within the larger pen and actively fly in and out of the pen at their own discretion, roosting at night as they continue to acclimate to the marshes. “Providing access to food sources in the pen early on was designed to attract the group back to the safety of the predator-proof enclosure at night,” said Tom Hess, LDWF-CNR biologist program manager. “Our concerns early on were for the birds to develop predator avoidance skills in a marsh environment also inhabited by alligators, bobcats and coyotes.”

The goal of the state’s reintroduction project is to establish a self-sustaining whooping crane population on and around White Lake, which contains over 70,000 acres of freshwater marsh. A self-sustaining population is defined as a flock of 130 individuals with 30 nesting pairs, surviving for a 10-year period without any additional restocking. Whooping cranes do not generally nest until 3-5 years of age, so the nesting success of the Louisiana group may take several years to be determined. The long-term goal of this reintroduction is to move whooping cranes from an endangered species status to threatened status. Future plans for the project include re-introductions of additional juvenile cohorts once or twice a year for the next two years. At that point, the project will be evaluated to determine the number of birds for released in future years.

The newly established whooping crane population at White Lake is designated as a nonessential experimental population (NEP) under the provisions contained within section 10(j) of the Endangered Species Act. The population is considered experimental because it is being reintroduced into suitable habitat that is outside of the whooping crane’s current range, but within its historic range. It is designated nonessential because the likelihood of survival of the whooping crane as a species would not be reduced if this entire population were not successful and lost. The NEP status will protect this whooping crane population as appropriate to conserve the population, while still allowing the presence of the cranes to be compatible with routine human activities in the reintroduction area. Examples of such activities include recreational hunting and trapping, agricultural practices (plowing, planting, application of pesticides, etc.), construction or water management.

Although designated as NEP, the Louisiana whooping cranes are still protected under law. Because of the experimental non-essential designation in this rule, if the shooting of a whooping crane is determined to be accidental and occurred incidentally to an otherwise lawful activity that was being carried out in full compliance with all applicable laws and regulations, no prosecution under the Endangered Species Act would occur. In the case of an intentional shooting, however, the full force and protection of the Endangered Species Act could apply. Additionally, the birds are protected under applicable state laws for non-game species and the federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act, which protects all birds that migrate such as herons, egrets and songbirds.

“We want anyone in the marsh near White Lake to enjoy the moment should they encounter one or more of the experimental birds in the wild during this re-population effort,” said Love. “As long as the cranes are observed at a distance, they should adapt to occasional human encounters.”

Project funding for Louisiana’s whooping crane project is derived from LDWF species restoration dedicated funds, federal grants and private/corporate donations. LDWF’s budget for the initial year of the project is $400,000. The project costs escalate in year two and beyond as the project expands. LDWF estimates it will be necessary to raise three to four million private dollars to help fund a portion of this 15-year project.

Private and corporate donations supporting the whooping crane project can be made to the Louisiana Wildlife and Fisheries Foundation. Gifts should be designated as “support of the Whooping Crane Project.” For information on the foundation and to obtain a donation form go to http://www.wlf.louisiana.gov/lwff. For more information on the historic re-introduction of whooping cranes to Louisiana, visit http://www.wlf.louisiana.gov/wildlife/whooping-cranes.

Carrie Salyers, Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries

Whooping Crane Telemetry Project Update

July 12, 2011As the previous newsletter detailed, in August 2010 researchers captured nine whooping crane chicks at Wood Buffalo National Park. This ongoing project intends to answer questions regarding whooping crane migratory ecology and behavior during migration using GPS. The project uses solar Argos Global Positioning System (GPS) Platform Transmitter Terminals (PTTs) attached to tarsal bands. Birds are also marked with color leg bands similar to those used from 1977-1988. At least eight of the chicks thus banded fledged, and successfully migrated to Aransas NWR. After spending the winter months in Texas, the family groups began heading north in late March, with most of them having reached WBNP by the first week of May.

Whooping crane family with banded individual. Photo by Cathie Foster

Researchers also conducted capture efforts at Aransas NWR this past January. Crane Capture Guru David Brandt (Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center) was ably assisted by Felipe Chavez-Ramirez (Gulf Coast Bird Observatory), Barry Hartup (International Crane Foundation), Edgar Lopez-Saut (CIBNOR La Paz), Claudia Doria-Treviño (UNANL) and Walter Wehtje (The Crane Trust). Using corn, fishing line and a fishing pole, we were able to capture an adult female whooping crane at the ANWR’s Lamar Unit on 8 January 2011. Given that this bird‘s territory included Lamar’s 8th Street, it quickly became the most viewed and photographed banded Whooping Crane in south Texas (pictured left). Adding the chicks banded at Wood Buffalo NP and the two birds banded in December 2009 at Aransas, we are now following 11 members of the Aransas Wood Buffalo Population of whooping cranes.

Under ideal conditions, the PTTs provide four GPS locations per day. These data are stored by the device and every 56 hours uploaded via satellite to Argos. From here, we download the data and analyze it using ArcGIS. This allows us to follow their migration in near real-time. With each PTT expected to provide data for at least three years, we are looking to learn much about the lives of these birds. The preliminary analysis has provided a wealth of detail and greatly increased our understanding of their migratory habits.

Spring migration routes taken by whooping cranes with gps transmitters. Figure courtesy The Crane Trust, Inc.

One of the most gratifying findings was that all of the juveniles survived their first migration experience. Except for one PTT that only functioned intermittently, we were able to follow each bird’s movements from Wood Buffalo down to Aransas (Pictured right). While the time spent in migration by the families varied from 14 to 48 days, the number of days during which they actually covered more than 30 km (18 mi) in flight ranged from 9 to 12. The balance of their time was spent at staging grounds in Saskatchewan, North Dakota and South Dakota. The maximum distance covered by one family in a day was 965 km (600 mi) at the end of which they spent the night in a recently harvested corn field; they must have been tired (cranes normally spend the night roosting in shallow water). The sub-adult that was banded in 2009 traveled with Sandhill Cranes throughout much of the fall. Once he reached Aransas he quickly moved to the salt marshes and associated with other whoopers for the whole winter.

The first banded family group departed Aransas on 21 March and the last left on 6 April. As of this writing most of the birds have arrived at Wood Buffalo NP and the adult female banded this past January is moving very little, suggesting she may already be incubating. Equally interesting has been the behavior of the yearling birds. One of them flew up to Wood Buffalo, but then flew back south and has now been in central Saskatchewan for the past week, where it appears that two other yearlings have also ended up. It looks as if every season will continue to bring new insights and surprises.

Walter Wehtje, The Crane Trust, Inc.