Archive for the ‘Aransas Updates’ Category

Wintering Whooping Crane Update

February 29, 2016Check out the December 22, 2015 update on Wintering Whooping Crane’s, by Dr. Wade Harrell, U.S. Whooping Crane Recovery Coordinator.

Wintering Whooping Crane Update, February 22, 2015

February 22, 2015Wade Harrell, U.S. Whooping Crane Recovery Coordinator.

It continues to look like a banner year in terms of habitat conditions, with the Refuge having a greater amount of freshwater on the landscape than we have seen in several years. Fall and winter rains are slowly moving us in the right direction. Whooping Cranes have responded to these conditions by spending more time in the coastal marsh, foraging on the relatively abundant blue crabs and other food resources. While we have still seen some Whooping Crane use of inland habitats this year, that trend is definitely down from the peak of the drought 2 seasons ago.

Visitors to the Refuge and those observing Whooping Cranes from boat tours have been in a good position this year to observe use of the traditional coastal marsh habitat. We’ve had some outstanding weather lately, and I encourage everyone to come out and visit us before the Whooping Cranes start heading back North in late March. Many of you will be happy to know that we have reinitiated our Refuge bus tours for February and March. Tours are first-come, first-served, and visitors must register in the visitor center the day of the tour.

Visitors to the Refuge and those observing Whooping Cranes from boat tours have been in a good position this year to observe use of the traditional coastal marsh habitat. We’ve had some outstanding weather lately, and I encourage everyone to come out and visit us before the Whooping Cranes start heading back North in late March. Many of you will be happy to know that we have reinitiated our Refuge bus tours for February and March. Tours are first-come, first-served, and visitors must register in the visitor center the day of the tour.

The schedule is as follows:

Thursday, 1:00 – 3:00 p.m.

Friday, 1:00 – 3:00 p.m.

Saturday, 10:00 a.m. – 12:00 p.m. and 1:00 p.m. – 3:00 p.m.

Sunday, 10:00 a.m. – 12:00 p.m. and 1:00 p.m. – 3:00 p.m.

Information on Whooping Crane Death Being Sought

The U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service and Texas Parks & Wildlife are seeking information about the death of a Whooping Crane. The carcass of the bird was found on January 4. For more information, please see the press release.

Training Surveys & GoPro Video

We were able to fly some training surveys on January 5-6 with our new Refuge Biologist Keith Westlake and Ecological Services biologist Frank Weaver. We are still working through the best way to utilize GoPro Camera technology in our survey efforts, but have some clips of how things look 200 feet above the marsh. We’ll be uploading the survey clips on our Facebook page, so check it out in the coming week.

GPS tracking study & other Whooping Crane observations

While we have not done any additional marking of Whooping Cranes this winter, we are still consistently tracking 20 GPS marked Whooping Cranes for this study. They also have bi-color bands on the leg opposite of the leg with the transmitter. If you happen to see a marked bird, please report it to us with as much information as you can (i.e. Red/Black left leg, GPS right leg, location, other birds in the same area, etc.)

Whooping Cranes outside the traditional wintering area that have been reported to Texas Whooper Watch include a single adult bird associated with a group of Sandhill Cranes in Eastern Williamson County, a pair of adult Whoopers near the town of Refugio, and a pair of adults with 2 juveniles in Northwest Matagorda County.

Habitat Management on Aransas NWR:

The Refuge successfully conducted 3 burns this winter, 2 on the Blackjack Peninsula along East Shore Road (primary Whooping Crane habitat) and one on Matagorda Island. Total acreage burned was more than 12,000 acres.

Recent Precipitation/Salinity around Aransas NWR:

December precipitation: 2.95” @ Aransas HQ

January precipitation: 2.85” @ Aransas HQ

February precipitation (as of Feb. 22): 0.93” @ Aransas HQ

Salinity at GBRA 1: averaging around 24 ppt

Wintering Whooping Crane Update

December 22, 2014Update from Wade Harrell, U.S. Whooping Crane Recovery Coordinator. Read Now…

WANTED

The Whooping Crane Conservation Association is currently seeking interested people to fill upcoming vacancies on our Executive. All executive positions, including those of the Trustees, are volunteer positions with no remuneration.

Secretary

We are seeking a person with organizational skills who is interested in becoming the secretary of the WCCA. The secretary is reponsible for keeping track of the membership information and donations. Proficiency with Microsoft ACCESS an asset.

Newsletter Editor

We are seeking a person with writing and organizational skills to put together our newsletter “Grus Americana”. The editor assembles articles of significance and then uses word processing software to form a newsletter. Proficiency with Microsoft Word or other word processing software an asset.

If you are interested in either of these positions, please use the Contact WCCA page. Thanks for your interest.

Whoopers Continue On Their 2,500 Mile Migration

April 16, 2013by Chester McConnell, Whooping Crane Conservation Association

Approximately 50 to 60 percent of the whooping cranes have departed from Aransas Refuge (Texas coast) on their long 2,500 mile migration to Wood Buffalo National Park in Canada. Wood Buffalo is where they nest and rear their young. Dr. Wade Harrell, U.S. Whooping Crane Recovery Coordinator continually monitors the whooper flock on Aransas National Wildlife Refuge. Harrell described the ongoing migration of the birds as normal this spring. He explained that, “Whooping cranes are still being observed on the refuge, but the migration is well underway.

Harrell explained that, “As of Monday, April 8, 14 of the telemetry marked birds that we are actively receiving data on were still present on the Texas coast and 21 have begun migration. Based on this information and other observations, it is likely that greater than 50% of the birds in the Aransas/Wood Buffalo flock are currently migrating north. Of the 21 marked whooping cranes currently in migration, 14 are as far north as Nebraska and the Dakotas.”

Harrell estimates that most remaining birds will depart from Aransas Refuge over the next couple weeks. He advised that, “Whoopers are scattered along the migratory path as far north as North Dakota. Though the birds seem to be leaving in mass, they actually have staggered departures and leave in small groups. This is important as it ensures survival of the species. If they were to all leave together and encountered bad weather or some other catastrophic event, it could put the whole flock in jeopardy.” Dr. Harrell’s migration information mirrors information collected by the Whooping Crane Conservation Association (WCCA). Many bird watchers and a variety of citizens observe whooping cranes and report then on WCCA’s web page https://whoopingcrane.com/ .

Anyone who spots a whooper can go the web page and click on Report a Sighting and complete a simple form. WCCA places the information received on a map during the spring and fall migrations. Anyone can keep up with the migration by clicking on https://whoopingcrane.com/migration/ .

Migration Map

WCCA’s Migration Map includes all creditable whooping crane observations from reports received. Each whooper “icon” on the map represents from 1 to 6 birds. Observations have been posted on the Spring Migration 2013 map since mid-March. Importantly, all postings are delayed at least one week to help prevent harassment of the birds. Because the whoopers move frequently during migration, it is highly unlikely that one can use the map to locate the birds.

Whooping Crane Update – Aransas National Wildlife Refuge (summary)

April 12, 2013 by Wade Harrell, U.S. Whooping Crane Recovery Coordinator

by Wade Harrell, U.S. Whooping Crane Recovery Coordinator

Whooping Cranes on the Refuge:

Birds are still being seen on the refuge, but the whooping crane migration is well underway and we expect that most birds will depart the coast over the next couple weeks. Based on the tracking data and incidental observations, it appears that the birds using the periphery areas of the winter range (i.e. Lamar, Granger Lake, El Campo, Welder Flats) have been the first to depart this year. Though the birds seem to be leaving in mass, they actually have staggered departures and leave in small groups. This is important as it ensures survival of the species. If they were to all leave together and encountered bad weather or some other catastrophic event, it could put the whole flock in jeopardy.

Tracking Efforts:

As of Monday, April 8, 14 of the marked birds that we are actively receiving data on were still present on the coast and 21 have begun migration. Based on this information and other observations, it is likely that greater than 50% of the birds in the Aransas/Wood Buffalo flock are currently migrating north. Of the 21 marked whooping cranes currently in migration, 14 are as far north as Nebraska and the Dakotas

Taking a look into the past as we consider the future:

The following graphic shows the expansion of wintering whooping cranes on and around the Refuge over the past 55 years (1951-2006). As we have seen this winter, this expansion has now moved to a few inland locations such as the Granger lake area. This trend gives us hope that the species will continue on the upward trend. To read the full report, click on: http://www.fws.gov/nwrs/threecolumn.aspx?id=2147517593

Lobstick Whooper Remains A Mystery

December 21, 2012Editor’s Note: During April 2012 a whooping crane was murdered in the vicinity of Miller, South Dakota. At the time there was speculation that the dead crane was one of the famous Lobstick pair. The speculation continues. Captain Tommy Moore operates a tour boat in the vicinity of Aransas National Wildlife Refuge and believes he knows the Lobstick pair is alive. I contacted Tom Stehn retired Whooping Crane Coordinator to inquire. Luckily, Tom was going out the next day on Captain Moore’s boat and wrote me the following report. Chester McConnell, Whooping Crane Conservation Association, Web Administrator.

by Tom Stehn, Retired Whooping Crane Coordinator

On December 19th, I rode the whooping crane tour boat named the Black Skimmer to help with the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge’s Audubon Christmas Bird Count. Our group counted over 9,300 birds of 77 different species, but I didn’t see the bird I wanted to see most. The Lobstick whooping crane pair was not on its territory! We did spot 35 other whooping cranes, but I missed seeing what might be the oldest known aged whooping crane in the flock.

The Lobstick male was banded in 1978 as a 3-month-old chick in Canada’s Wood Buffalo National Park. After pairing up and successfully raising a chick in 1982, the Lobsticks continued their prolific breeding to become one of the most productive pairs in the flock. They have brought 17 chicks to Aransas in 31 years of nesting, and twice pulled off raising two chicks. Unfortunately, they have not made it to Aransas with a chick for the last three winters. The Lobstick male would now be 34, assuming he is still alive. His bands have fallen off, but voice printing multiple years ago of the male’s unison call had shown the same bird was present.

The pair continues to nest on Lobstick Creek just outside of Wood Buffalo National Park and defend the same territory on Aransas. They are often the first pair the whooping crane tour boats see. In the 2008-09 winter, the Lobstick male had difficulty flying for a spell, and the following winter we weren’t sure if he was present as the pair roamed more and was seemingly absent on several flights and boat trips. However, Captain Tommy Moore to this day continues to sight a crane pair on the Lobstick territory with a very large male that sometimes approaches the tour boat that could be Lobstick. Tommy thinks Lobstick is still alive. I don’t know for sure, but I’d like to think that 34-year-old old codger is still patrolling its Aransas territory as it keeps a glaring eye out for blue crabs and other cranes foolish enough to intrude on his territory. I didn’t see him the other day, but the refuge had recently done a prescribed burn, and I bet Lobstick had been on that upland area looking for roasted acorns. Other species of cranes have been known to live in captivity for over 80 years, so don’t count old Lobstick out.

Whooping Crane Conservation Association…working to conserve Whooping Cranes

December 16, 2012by Chester McConnell and Jim Lewis, WCCA

The Whooping Crane is the symbol of conservation in North America. Due to excellent cooperation between the United States and Canada, this endangered species is recovering from the brink of extinction. Their population increased from 16 individuals in 1941 to 588 wild and captive birds in September 2012. The name “Whooper” probably

came from the loud, single-note call they make when disturbed. The adult is 5 feet tall, the tallest bird in North America. When the wings are extended they are 7 feet from tip to tip. They are graceful flyers, elegant walkers, and picturesque dancers. Adults are a beautiful snowy white with black outer wing feathers visible when the wings are extended. The top of the head is red with a black cheek and back of neck, yellow eyes, and gray-black feet and legs.

Soft down covering the cute baby chicks is buff-brown. At about 40-days-of-age, cinnamon-brown feathers emerge. When they are one-year-old they have their white adult plumage.

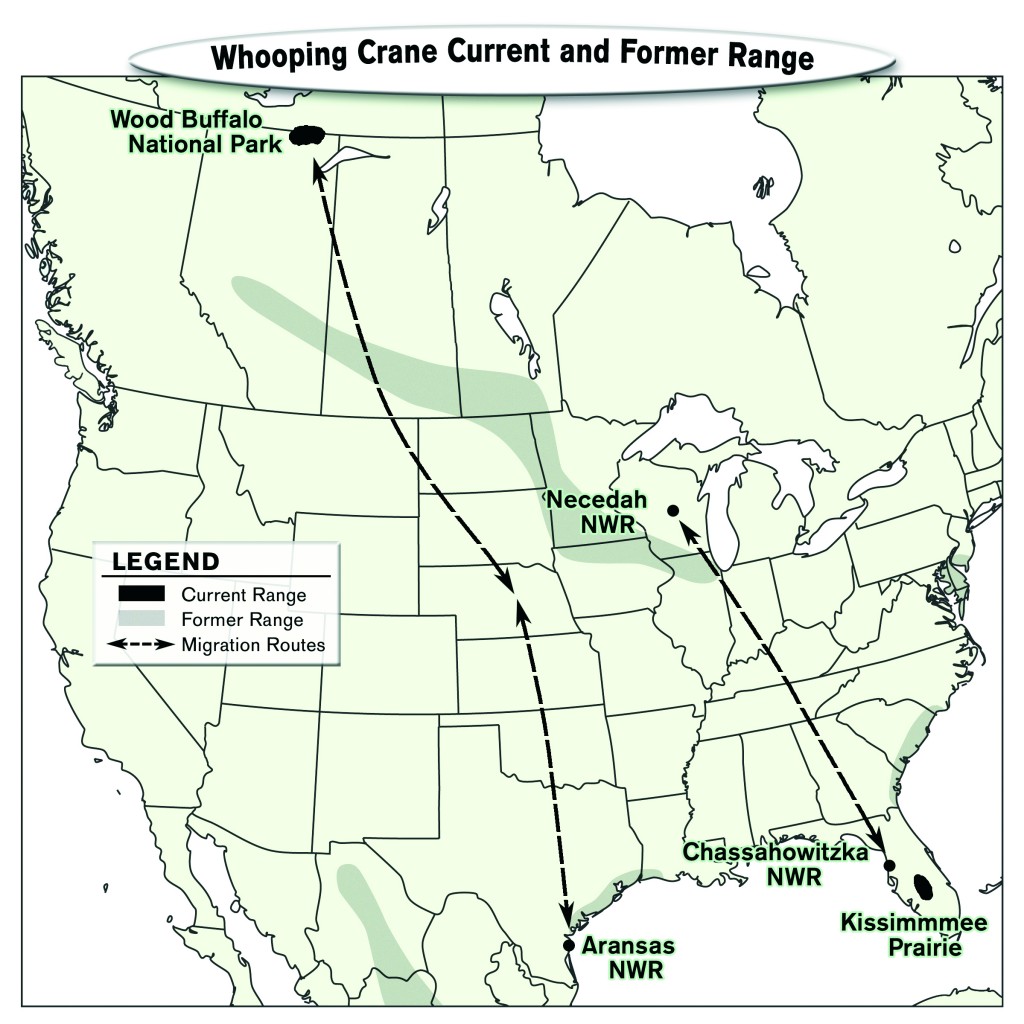

Despite progress in increasing the numbers of these birds, only one population maintains its numbers by rearing chicks in the wild. This flock now contains about 300 birds that nest in Wood Buffalo National Park, in the Northwest Territory of Canada. They migrate to the Gulf Coast of Texas on Aransas National Wildlife Refuge and bordering private land where they spend the winter. It is on their wintering ground where they are especially vulnerable. A hurricane could destroy their habitat and kill birds, or an oil spill could destroy their foods. Less abrupt, but equally dangerous, is diversion of river waters that flow into the crane’s habitat. This fresh water is being used upstream for agriculture and for human uses in cities. The steadily diminishing flow into the Gulf of Mexico is making the area less productive for Whooping Crane foods. They need these foods to remain healthy, and to fatten for strength on their 2,500-mile migration and for producing young when they arrive in Canada where winter is just ending.

Whooping Cranes were once more abundant in the 1800s, nesting in Illinois, Iowa, the Dakotas, and Minnesota northward through the prairie provinces of Canada, Alberta, and the Northwest Territory. Drainage and clearing and of areas for farming destroyed their habitat, and hunting reduced their numbers. The only wild population that survived by the 1940s was the isolated one nesting in Northwest Territory. In March-April these cranes fly from Texas across the Great Plains and Saskatchewan to reach their nesting area.

They begin pairing when 2 or 3 years old. Courtship involves dancing together and a duet called the Unison Call. Whooping Cranes mate for life. Females begin producing eggs at age 4 and generally produce two eggs each year. Usually only one chick survives. The pair returns to the same area each spring and chases other cranes from their nesting area that is called a “territory”. It may include a square mile or a larger area. Chasing other cranes away ensures there will be enough food for them and their chick. At night they stand in shallow water where they are safer from danger.

They build a nest in a shallow wetland, often on a shallow-water island. The large nest contains plants that grow in the water (sedges, bulrush, and cattail) and may measure 4 feet across and 8 to 18 inches high. The parents take turns keeping the eggs warm and they hatch in about 30 days. The two eggs are laid one to two days apart so one chick emerges before the other. They can walk and swim short distances within a few hours after hatching and may leave the nest when a day old. The chicks grow rapidly. They are called “colts” because they have long legs and seem to gallop when they run. In summer, Whooping Cranes eat minnows, frogs, insects, plant tubers, crayfish, snails, mice, voles, and other baby birds. They are good fliers by the time they are 80 days of age. In September-October they retrace their migration pathway to escape winter snows and reach the warm Texas coast. During migration they stop periodically to rest and feed on barley and wheat seeds that have fallen to the ground when farmers harvested their fields.

In Texas they live in shallow marshes, bays, and tidal flats. They return to the same area each winter and defend their “territory” by chasing away other cranes. The territory may contain 200 to 300 acres. Winter foods are primarily blue crabs and soft-shelled clams but include shrimp, eels, snakes, cranberries, minnows, crayfish, acorns, and roots.

An individual bird may live as long as 25 years. But, Whooping Cranes face many dangers in the wild. Coyotes, wolves, bobcats, and golden eagles kill adult cranes. Bears, ravens, and crows eat eggs and mink eat crane chicks. When they are flying in storms or poor light they sometimes crash into power lines. And they die of several types of diseases.

In addition to the single self-sustaining population there are birds in captivity at seven locations and three other wild populations began as experiments to try to ensure that Whooping Cranes survive in the wild. There are 183 cranes in captivity including 23 young. Most of the young are released into the wild as part of the three experiments. In the first experiment, begun in 1993, juvenile captive-reared cranes were released in the Kissimmee Prairie of central Florida. Additional young cranes were released there each year. This is a cooperative effort by U.S. and Canadian federal agencies, the state of Florida and the private sector, to start a population that does not face the hazards of migration. Cranes learn a migration route from their parents. These cranes were raised in captivity so they did not learn to migrate. There were 87 cranes in this flock in 2003 including 7 adult pairs that successfully raised 3 young to flight age. Only 20 remain in 2012.

In 1997, Kent Clegg was the first individual to teach captive-reared Whooping Cranes to fly and follow a small aircraft. He led them in an 800-mile migration in the western United States. His technique was then used in the second experiment beginning in 200l to establish a population that nests in Wisconsin and migrates to western Florida. U.S. and Canadian federal agencies, provincial and state governments, Operation Migration, Inc., and other private sector groups are cooperating in this experiment. This flock now contains 104 cranes and others will be added in future years. The annual releases will stop when the two experimental populations produce enough young to maintain their numbers. Another non-migratory flock with 20 whooping cranes was established in Louisiana in 2011.

HOW YOU CAN HELP

You can help the endangered Whooping Crane recover its numbers so it can survive as a species. Join the Whooping Crane Conservation Association (WCCA) by clicking on: https://whoopingcrane.com/membership/ The WCCA is a nonprofit organization and your donations are tax deductible. The Association helps purchase habitat, fund research and management projects that aid Whooping Cranes and assists in educating the public about the dangers to this beautiful bird. As part of your membership, you will receive a handsome newsletter twice a year. The newsletter provides the latest information on status of the various populations, recovery progress, and other items of interest. ell others about the dangers to this bird and what is being done to benefit them.

WCCA’s web page at www.whoopingcrane.com includes current information, interesting facts and a coloring book for children.

Stehn Frustrated With New Whooper Count Method

December 6, 2012MY OPINION ON THE CURRENT WHOOPING CRANE COUNT METHODS

BY: Tom Stehn

Retired Whooping Crane Coordinator

Aransas Pass, TX 78336

The whooping cranes are back at Aransas, and the Refuge has started their winter whooping crane counts. After I retired in the fall of 2011, count methods were changed from the complete census done for the past 61 years to a survey method using hierarchical distance sampling. I was told this was done for policy reasons, and that there were now too many whooping cranes to count them all. The latter statement is untrue; I successfully counted the cranes for 29 winters, including a peak of 282 whooping cranes, and feel a complete census will work with a flock size of at least 500. It may be that on some future date, it will be appropriate to sample the population rather than count all individuals, but I do not believe that date has yet arrived.

The new survey methods employ fixed transects flown at 1,000 meter intervals over four hours, whereas the census transects I used averaged ~400 meters wide and flights lasted approximately six hours. It is incomprehensible how the new survey method that finds fewer cranes is considered better than an actual census. To me, the more cranes you actually locate, the more you are going to learn. Why settle for an “estimate” when you have the opportunity to count nearly every individual each time you fly?

For the first winter since the refuge was established in 1937, no peak flock size was obtained in the 2011-2012 winter using the new distance sampling methods. Yes, the cranes were more dispersed that winter due to minimal food resources at Aransas, and the Service had difficulty finding approved aircraft to conduct the flights. Even given these difficulties, I would have come up with a peak population estimate using my old census methodology. Last winter, the new distance sampling methodology estimated 254 plus or minus 62 whooping cranes in the survey area. No one knew if the flock had increased or decreased in size from the previous year. This degree of uncertainty is simply unacceptable and useless for recovery management purposes. I believe the census methods I employed had no more than a 2% error. I knew I was not off by much since the results were so consistent from week to week. The number of adult pairs on the wintering grounds always agreed closely with the number of nesting pairs found the following summer in Canada. I averaged finding 95% of the cranes on every flight, and multiple flights over the winter season allowed me to put together the jigsaw puzzle of the flock composition (adults, subadults, juveniles, territory locations, mortality, habitat use, etc). The new survey methods do not attempt to locate territories or detect mortality, two actions recommended in the Recovery Plan.

Because the new survey methods are unproven and stakeholders are skeptical, I believe it would be prudent to continue to use the old census method while experimenting with the new method. Only when the new method is shown to be better should it be employed as the only survey methodology. I have written a letter to the Director of the USFWS and to the Director of Region II asking that they insure the flock gets censused this December before it is too late to obtain a peak count. If you agree with me, perhaps you might write a letter.

Whooping cranes are too valuable and too endangered not to count them annually to monitor how the flock is doing and how they are being impacted by numerous threats (sea level rise, housing developments, long-term decline of blue crabs, drought, invasion of black mangrove, power line and wind tower construction in the flyway, habitat loss, etc). For many, the whooping crane is considered the flagship species of the Endangered Species program. Because of this high level of interest and scrutiny, an accurate count is of great interest, both nationally and internationally. We owe it to the American people, our Canadian partners, and other conservation partners to provide them with the level of accurate information to which they have become accustomed.

Although happily retired, I’m frustrated by the people involved with the count insisting that their new methods are “better” when results to date prove they are not. One can’t expect me to be objective, but on the other hand, I have as much knowledge as anybody of counting whooping cranes. I urge the USFWS to utilize transects no more than 500 meters apart which will enable them to find a much higher percentage of the crane flock. Why not do a census using 500 meter transects one day and conduct a distance sampling survey at 1000 meter transects the next day to compare methods? Biologists can then decide if distance sampling is a useful tool. But at five feet tall and with nothing to hide behind, it is not hard to find nearly every whooping crane from the air. Come on Fish and Wildlife Service; use the count methods that are the most effective.

Rare Whooping Crane Photo

November 13, 2012by Chester McConnell

Whooping Crane Conservation Association

Getting good photographs of members of the Aransas-Wood Buffalo flock of whooping cranes is not easy. First they are wild and cautious. And then there are so few of them (about 300). Generally they are in locations not easy to get to. During this time of year the whoopers are migrating from their nesting habitat in Wood Buffalo National Park, Canada to Aransas National Wildlife Refuge along the Texas coast. They may be observed anywhere along the 2,400 mile migratory route if you are lucky.

Photographer Mike Umscheid is one of those lucky people but I believe that his luck improves the harder he works. Mike recently made some excellent photos of whooping cranes and agreed to share them with the Whooping Crane Conservation Association (WCCA).

Mike’s photo shown below is very unusual because there are 16 whoopers flying together. Two more were with the group. Normally whooping cranes fly in groups of 2 to 8, so a photograph of 16 together is very unlikely.

WCCA communicated with Mike and we share with you his excitement about his recent encounter with the cranes. Mike advised: “I’ve visited the WCCA website before, even before I photographed those cranes, in gathering information on movement of the whoopers, the latest flock numbers, etc. I’ve fallen in love with the whooping crane and it is a bird that I have always wanted to photograph. Needless to say, it was an absolute treasure being around them and having them fly above me (let alone photographing them).”

Mike continues: “I was out at Quivira (National Wildlife Refuge, Kansas) photographing cranes for a couple of days recently. The surge of cranes began to arrive there earlier last week. The whooper numbers peaked at 18, and all 18 of them were on the Little Salt Marsh (LSM) at that time. The day before, my partner (Jim Glynn), and I photographed 3 whoopers as they flew just about directly overhead as they lifted off to feed around 10:30 in the morning. I got some fairly nice nearly frame-filling images of these birds in flight.” (WCCA has omitted the specific times and locations of the whooping cranes to help prevent possible harassment of the birds. Most whooper visits occur overnight and are gone from the area by mid-morning the next day.)

After photographing the many sandhills on Big Salt Marsh (BSM), Mike and Jim slowly made their way to another site to see if they could observe the whoopers again. Sure enough, they located them again way out in the middle of a marsh. Mike explained: “At first there were two subgroups of 13+5, but then they all converged before taking flight to head south. The 16 adults and 2 juveniles took flight, a scene I’ll never forget. We were repositioning ourselves as they lifted off, so I didn’t get any images of the lift off, as the flapping, stark black wing tips were lined up one by one like a series of aircraft departing off a runway. We grabbed some amazing in flight shots in good front light as they were flying towards us — all 18 of them!”

Mike added, “In several of my images, I noticed one adult did have a GPS tracking unit on one of its legs and was banded. All the other birds were device/banded free. It was a moment I never anticipated I would get to experience, and I have only had my 600mm lens for less than a month! All my in-flight images were shot with a Nikon D3, 600mm f/4 lens with 1.4x teleconverter.

Whooping Cranes Continue Migration South

October 27, 2012By Chester McConnell, Whooping Crane Conservation Association

Whooping cranes are on the move southward and have been spotted all along the migration pathway. The Whooping Crane Conservation Association has received reports of cranes along their migratory path from Saskatchewan, Canada to Aransas, Texas.

Martha C. Tacha, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Nebraska reports that, “The whooping cranes with GPS transmitters are on the move, with the bulk of these marked cranes in North Dakota and South Dakota, and two already in Texas. We know that one unmarked whooper stopped over at a lake near Oklahoma City recently. While the early confirmed sightings have been single birds, there was a group of nine adult-plumaged whoopers in northern North Dakota recently.”

One of the GPS transmitter marked whooping crane arrived on the Texas coast on October 18 and has been using the marsh habitat extensively. Aransas National Wildlife Refuge officials report that, “All other GPS marked whooping cranes are north of South Dakota awaiting favorable migration conditions. Biologists expect the cranes will take advantage of the strong north winds associated with seasonal cold fronts. On October 23 Aransas Refuge Biologist Brad Strobel and Refuge Manager Dan Alonso observed one adult whooping crane feeding in the refuge marshes on the Blackjack peninsula. The bird ate at least two prey items during the 3-5 minutes it was observed.

The winter home of the whooping cranes at Aransas Refuge is improved compared to this time last year. Refuge personnel advise that salinity levels in the bay waters are fresher than they were at this time last fall and winter. The salinity levels in San Antonio Bay were recorded as 23.9 parts per thousand.

Aransas Refuge also has experienced improved rainfall in recent months. According to refuge officials, to date, the refuge has received 25.6 inches of rain, which is a foot more than we had last winter at this time. The area is still unusually dry but the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration predicts south Texas will see a wetter than average winter and spring in 2013. To make certain freshwater is available to the whooping cranes when they arrive, refuge staff have been working on water well sites previously used by cranes on the Blackjack peninsula to ensure they are in good working condition.

Whooper food sources on the refuge have also improved during this growing season. Refuge biologists have noticed many flowering and budding wolfberry plants while conducting field work during the last few weeks. Wolfberry conditions in the marsh appear to be much better than this time last year. Peak berry abundance typically occurs in November and December and the plants seem to be on schedule according to biologists. Blue crabs also appear to be abundant in the marsh currently based on surveys conducted by refuge personnel.