Archive for the ‘Endangered Species’ Category

South Dakota Man Guilty of Whooping Crane Murder

February 14, 2013Miller Man Sentenced for Killing endangered species

February 13, 2013, U.S. Attorney’s Office, District of South Dakota; Contact: Ace Crawford, 605-343-2913 ext. 2101

United States Attorney Brendan V. Johnson announced that a Miller, South Dakota man pled guilty and was sentenced for killing an endangered whooping crane.

Jeff Blachford, age 26, appeared before U.S. Magistrate Judge Mark A. Moreno on February 13, 2013 and pled guilty to one count of violating the Federal Endangered Species Act. Blachford was sentenced to $85,000 in restitution, 2 years of probation, and a $25 assessment to the Victim Assistance Fund. Blachford was additionally ordered to forfeit the rifle he used in the offense and is prohibited from hunting, fishing, or trapping anywhere in the United States for two years.

“Wildlife is an important resource to the people of South Dakota. This year marks the 40th anniversary of the Endangered Species Act, and the sentence handed down today for the senseless killing of a whooping crane, one of the rarest birds in the world, is a prime example of the enforcement of that law,” said Johnson. “The Department of Justice works hand in hand with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and takes the killing of endangered species very seriously. Let this case serve as notice to anyone who thinks otherwise.”

In April 2012, Blachford shot and killed an adult male whooping crane approximately 17 miles southwest of Miller. “The killing of this whooping crane was a senseless act and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is pleased with the sentence handed down in this case,” said Deputy Chief Edward Grace of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Office of Law Enforcement. “The protection of endangered species is a high priority for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and our Special Agents, in partnership with the South Dakota Department of Game, Fish and Parks, will continue to aggressively investigate these types of violations to ensure these animals receive the protection they need to survive.”

Whooping cranes are one of the rarest birds in the world with a total population of approximately 600 individuals. The whooping crane killed in this case was one of about 300 wild whooping cranes that migrate from wintering grounds along the gulf coast of Texas to the Woods Buffalo State Park located in Alberta and the Northwest Territories of Canada. This population of whooping cranes is the only self-sustaining population in the world.

This investigation was conducted by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Office of Law Enforcement and the South Dakota Department of Game, Fish and Parks. Assistant U.S. Attorney Meghan N. Dilges prosecuted the case.

First Incidental Take Permit for Whooping Cranes at an Individual Wind Farm

February 7, 2013by Chester McConnell, Whooping Crane Conservation Association

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) is considering issuing the first-ever Incidental Take Permit to a wind farm for endangered Whooping Cranes and threatened Piping Plovers. If FWS grants the permit, the Merricourt Wind Power Project in North Dakota would be protected from prosecution under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) for killing Whooping Cranes and Piping Plovers.

Whooping Crane Conservation Association contends that: 1) FWS failed to give the public adequate notice on an important endangered species issue, 2) the agency is only preparing an Environmental Assessment for a precedent-setting take permit of significant environmental impact, and 3) there are fewer than 300 individual Whooping Cranes left in the wild Aransas/Wood Buffalo flock which migrates through North Dakota.

The Merricourt Wind Project proposes to build 100 turbines within a 22,400 acre project area and build 33 miles of access roads. FWS has advised the project developer that the wetland stopover habitat in the project area is critical to the survival and recovery of the Whooping Crane. The site is also about two miles from designated critical habitat for Piping Plovers. In addition, FWS has told the developer that three ESA candidate species may be present at the site (Sprague’s Pipit, Dakota skipper, and Powesheik skipperling).

Whooping Crane Conservation Association president Brian Johns recently wrote a letter to the project manager explaining the Association’s position. President Johns wrote: “The Whooping Crane Conservation Association (WCCA) would like to express our concerns over the placement of the proposed Merricourt Wind Power Project in North Dakota. Wind Power projects have been identified in the International Recovery Plan for the Whooping Crane as a potential threat to flying Whooping Cranes. As you know the Whooping Crane is listed as Critically Endangered by the IUCN as well as both the United States Fish and Wildlife Service and the Canadian Wildlife Service. The Aransas/Wood Buffalo population (AWBP) which contains fewer than 300 individuals is the only self-sustaining wild population of whooping cranes. With such a limited population, the genetic contribution of each individual is critical to the survival of the species.”

The Merricourt Wind Project proposes to build 100 turbines within a 22,400 acre project area and build 33 miles of access roads.

John’s letter continues: “The proposed placement of this wind power project directly within the migration corridor of the AWBP seems like an accident waiting to happen. We understand that the USFWS may grant an Incidental Take Permit, which would allow the project to proceed. The WCCA is opposed to locating any wind power projects within the migration corridor. If such a project were to proceed, we would expect the USFWS to ensure that all mitigation measures listed in the Whooping Crane Wind Development Issue Paper are taken to avoid harm to the AWBP of Whooping Cranes.”

Brian Johns New President of Whooping Crane Conservation Association

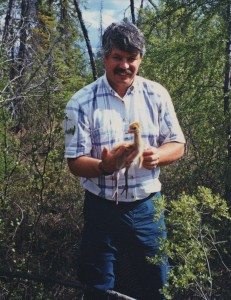

February 4, 2013Brian Johns of Canada has assumed the role as President of the Whooping Crane Conservation Association for 2013. Brian replaced Lorne Scott. Scott, also a Canadian, will remain as a Trustee with the Association.

Brian Johns, Canadian Wildlife Service (retired) with whooping crane chick, Wood Buffalo National Park. Brian was recently elected as President, Whooping Crane Conservation Association.

Brian Johns is a retired wildlife biologist with the Canadian Wildlife Service (CWS). He received his Bachelor of Science Advanced degree from the University of Saskatchewan in 1973 and began his career with the CWS that same year. During his time with the CWS Brian conducted research on sandhill cranes, whooping cranes, loggerhead shrike and various songbirds in the grasslands, parklands and boreal forests of Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba.

In 1981 Brian began monitoring whooping crane migration through prairie Canada and participated in the whooping crane radio tracking program. Between 1984 and 1987 he researched habitat use by migrant whooping cranes. Brian began directing the CWS whooping crane program in 1992 and has been involved in research and monitoring studies of Whooping Cranes on the breeding grounds in Wood Buffalo National Park and along their migratory flyway.

Brian’s research has included population monitoring, philopatry, effects of egg collection and the banding of juvenile whooping cranes. Brian has also studied potential reintroduction habitat in Saskatchewan and Manitoba and tracked sandhill crane migration routes from those habitats. He has logged over 1500 hours of aerial surveys over the crane nesting area.

Brian is the past chair of the National Loggerhead Shrike Recovery Team and Canadian Whooping Crane Coordinator. He co-chaired the Canada/United States Whooping Crane Recovery Team from 1995 – 2009. He is the recipient of Nature Saskatchewan’s Conservation Award and the Whooping Crane Conservation Association’s Honor Award and the Jerome Pratt Whooping Crane Award. Brian retired in 2009 after 36 years with the CWS.

Photographing a Whooping Crane

January 22, 2013Editor’s note: Our members and viewers of our web site often write us about their observations of whooping cranes. Some even send us photos. We always appreciate these. We enjoy sharing some of these submissions with you. We just received some photographs from Carol Mattingly. She also wrote about her experience. Her article is posted below. If you have interesting experiences and photos and would like to have us place them on the web site, please go to our web site whoopingcrane.com . Then click on “Report A Sighting” and fill out the form and click “Send”.

Photographing a Whooping Crane

By Carol Mattingly, Carol Mattingly Photography

Turning left onto a two lane dirt farm road, I edged my car just past an unplowed field and there standing in several inches of water picking at the ground in hopes of finding food was a beautiful adult Whooping Crane. How he could possibly find anything to eat in this field made me wonder. This region had just experienced the most severe drought in recorded history just this past summer. The seeds planted in these fields could not possibly have yielded any crops. Possibly weed seeds and insects were there.

It was a sunny Sunday afternoon and I had made my way to south Indiana just on the other side of a river bridge. The Bottoms is generally what the locals call this area. And after heavy rains the week before, I could see why it is called bottomland. There were large pools of standing water in all of the fields.

And for as far as the eye could see, on this particular Sunday, there were hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of Sandhill Cranes. And standing amongst the Sandhills was this one solitary Whooping Crane. I wondered if it had mated with one of the Sandhill Cranes and would it be traveling with this huge flock of Sandhill Cranes for years to come.

Seeing my first Whooping Crane was a fantastic treat, but getting a fairly decent image of the crane was ever better. I did not want to get too close for fear of frightening the birds. The Whooping Crane stood for some time looking around and I knew that was my opportunity to snap a few images. I love the way the Sandhill Cranes feathers lay across the back of their rump in a poof. But this Whooping Crane’s white feathers lying across his rump was so beautiful. I wonder if he knew he was the star of the show that Sunday. See my photo below:

The Man Who Saved the Whooping Crane

January 13, 2013Preface: After having read Kathleen Kaska’s book, “The Man Who Save the Whooping Crane: The Robert Porter Allen Story”, I needed to know more about this man who, if it hadn’t been for his dedication and perseverance, there probably wouldn’t be whooping cranes today.

While searching for every morsel of information pertaining to the whooping cranes before and during Allen’s time, I often thought of what a wonderful adventure and treasure hunt Kathleen must have had doing her research for the book. I contacted Kathleen to ask if she would like to write a short article outlining her feelings and experiences while researching “The Man Who Saved the Whooping Crane”. Immediately, she responded with “yes” and that she would love to. Below is an account of her adventures, which she has graciously written for us.

Thank you, Kathleen for sharing the life of Robert Porter Allen and your adventures of researching and writing the book.

Pam Bates, Whooping Crane Conservation Association ———————————————-

The Man Who Saved the Whooping Crane: The Robert Porter Allen Story

by Kathleen Kaska

By the time I began writing about the life and adventures of Robert Porter Allen, several decades had passed since he traipsed through the Canadian wilderness in search of the whooping crane’s last nesting site.

I first became aware of Allen’s work while designing an environmental/ecology unit for my

seventh-grade science class. The school librarian provided me with a National Geographic video about the efforts that had been made to save the whooping crane from extinction. The video briefly touched on Allen’s contributions, but it was enough to peak my interest. A few weeks later, I headed for the Texas coast to see the cranes on their wintering grounds at the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge. I’ll never forget that cold morning when I stood on the deck of the Wharf Cat tour boat gazing at those majestic birds through my binoculars—they simply took my breath away and at that moment I, too, wanted to make a difference in the whooping crane’s survival.At the time, I was also writing for Texas Highways magazine. When I returned home, I fired off a query to the editor, offering to write a story about Allen and the plight of the cranes. While researching the article, I realized that Allen had all but been forgotten. I felt his contribution to the world of ornithology and his story about his efforts to save the whooping cranes were too important to be lost. I decided to turn my research into a book.

Allen died in 1963. Considering all the time that had passed, finding someone who knew him well enough to paint a vivid picture of the Audubon ornithologist seemed an impossible task. I called the Florida Audubon chapter, located at the Tavernier Science Center, and learned that his daughter, Alice Allen, was living in Tavernier. I called her and introduced myself and told her about my plans. A few weeks later, I was on a plane to Florida.

Alice was only a young girl at the time her father had been named the director of the Whooping Crane Project in 1946. She was most generous in sharing her recollections of her father’s work, but I needed a wider perspective. I then visited the Science Center where most of Allen’s correspondences, published articles, photographs, and hand drawn maps are kept. Thanks to resident biologist, Pete Frezza, I even had the opportunity to motor out into Florida Bay to Bottlepoint Key where Allen had conducted his spoonbill research in 1939.

I had enough information to write the book proposal, which I eventually sent to University Press of Florida. By the time I received word of the book’s acceptance, my husband and I were on a two-year across-country retirement trip. Coming along with us on the trip, and taking up too much space in the truck of our car, were my research notes, tapes, and books. Over the next several months, I wrote the book in while on the road.

After it’s publication, I began giving presentations, which I entitled “On the Trail of a Vanishing Ornithologist,” named after Allen’s award-winning book, On the Trail of Vanishing Birds. That road trip provided me with the opportunity to visit sites I was writing about: Allen’s hometown in South Williamsport, Pennsylvania, Cornell University where Allen was enrolled in the early 1920s, Hopper’s Landing in Texas where Allen lived while working on the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge, and what proved to be invaluable, a second trip to see Alice and visit the Tavernier Science Center. Alice had uncovered more photos and information. Dr. Jerry Lorenz, the director of the Audubon Center and Flamingo Research Project and Allen successor twice removed, provided me with Allen’s research journals. These journals not only contained detailed accounts of his research, but also personal information; his feelings about being away from home and missing his family; his frustration with delays in moving forward with the Whooping Crane Project; his views on captive breeding program; anecdotes of his travels, which gave me a greater insight to his charismatic personality and sense of humor.

Most of the locations we visited were on our agenda. However, one particular serendipitous event led to an unbelievable experience. While traveling through Florida just south of Tallahassee, we noticed Wakulla Springs State Park, a hot spot for birding, was only a few miles away. We made a slight detour and upon arrival, checked into the historic Wakulla Spring Lodge for a two-night stay.

That afternoon on the birding boat tour, I met Betty and Lou Kellenberger, wildlife photographers and whooping crane devotees. They told me about the Whooping Crane Festival coming up that weekend at St. Mark’s National Wildlife Refuge. Representatives from Operation Migration (OM) and the International Crane Foundation (ICF) were speaking. That’s all I needed to hear. We added two more nights to our stay so I could attend. Although I missed seeing OM ultralight pilot, Brooke Pennypacker, I met Joan Garland with ICF. I told her about my book and she invited me to tour the ICF in Baraboo, Wisconsin later that year.

Looking at our map and calendar, I realized the Necedah National Wildlife Refuge, the location where OM trains whooping crane chicks to migrate, was nearby and that we’d be driving through the area during the time the Class of 2012 chicks would be training. About a week before we arrived in Wisconsin, I emailed Joan and asked if we could watch one of the training exercises. She made a few phone calls, and on the morning of August 12, my husband and I stood in a bird blind with pilot Richard van Heuvelen and lead technician Barb Clauss, both dressed in crane costumes, as they explained the morning’s training plan. Richard left to revive up the ultralight while Barb prepared to released the chicks. Watching those gangly young whoopers rush out of their pen and take to the air was one of the best moments of my life. I had to choke back tears. My husband, who’d spent years listening to me talk about OM, turned to me and said, “Now, I get it.” There were tears in his eyes, too.”

Visiting these sites, discovering Allen’s journal, and watching those chicks fly was just what I needed to give The Man Who Saved the Whooping Crane: The Robert Porter Allen Story, that special emotional element to transform the book from a mere biography into a true-life adventure story.

The book was released on September 16, 2012. Shortly afterwards, I received word that it had been nominated for the George Perkins Marsh Award for Environmental History.

Here’s an excerpt of the book:

It was April 17, 1948 in the early hours of a muggy Texas morning on the Gulf Coast. The sun at last burned away the thick fog that had settled over Blackjack Peninsula. The world’s last flock of wild whooping cranes had spent the winter feeding on blue crab and killifish in the vast salt flats they called home. During the night, all three members of the Slough Family had moved to feed on higher ground about two miles away from their usual haunt. The cool, crisp winter was giving way to a warm balmy spring, the days were growing longer, and territorial boundaries were no longer defended. Restlessness had spread throughout the flock.

As Robert Porter Allen drove along East Shore Road near Carlos Field in his government issued beat-to-hell pickup, he spotted the four cranes now spiraling a thousand feet above the marsh. He pulled his truck over to the roadside and watched, hoping to witness, for the first time, a migration takeoff. One adult crane pulled away from the family and flew northward, whooping as it rose on an air current. When the others lagged behind, the crane returned, the family regrouped, circled a few times and landed in the cordgrass in the shallows of San Antonio Bay. It was Allen’s second year at the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge. He had learned to read the nuances of his subjects almost as well as they read the changing of the seasons.

In the days preceding, twenty-four cranes left for their summer home somewhere in Western Canada, possibly as far north as the Arctic Circle. This annual event, which had been occurring for at least 10,000 years, might be one of the last unless Allen could accomplish what no one else had. The next morning when Allen parked his truck near Mullet Bay, the Slough Family was gone, having departed sometime during the night. That afternoon, he threw his gear into the back of his station wagon and followed.

THE MAN WHO SAVED THE WHOOPING CRANE: THE ROBERT PORTER ALLEN STORY—September 2012: University Press of Florida

Whooper Nesting Grounds Located (History)

January 2, 2013****History Briefs compiled by Whooping Crane Conservation Association****

Editor Note: For many years no one knew exactly where whooping cranes nested. Until 1954 whooping crane interests only knew that the birds migrated from “somewhere” in Canada to the Texas Coast. Crane interests had watched as the whooper population declined to 16 individuals in 1941. Pressures were brought on government agencies to protect and manage the birds. It was important to locate the whooper nesting habitats so these essential areas could be protected. In 1954 the whooping crane nesting area was finally located. The story is an interesting part of history. Whooping Crane Conservation Association member Pam Bates researched the literature and came across an article published in “Wild Lands Advocate” that tells the story. This is a follow-up to another article on our web page published on December 23, 2012. Click on the following link for the related story: https://whoopingcrane.com/whooping-cranes-from-despair-to-hope-to-progress/

DISCOVERY OF THE NESTING GROUND OF THE WHOOPING CRANE *

by Dr. W. A. Fuller

I have received a lot of credit for the discovery in 1954 of the only whooping cranes in Canada, but if it hadn’t been for the fire and an observant forester named George Wilson, I might never have gone out to identify the birds. The last nest of a whooping

crane had been seen in about 1926 in Saskatchewan. Members of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USWS) and others had searched from central Saskatchewan to the delta of the Mackenzie River without success. The USWS was interested because whoopers migrated to Texas.In 1945 I spent the summer working on fish in Lake Athabasca. At the end of the summer I decided that I would never return to the north. However, in 1946 I signed up to spend the summer at Great Slave Lake. The following winter I put together all the data that had been gathered over several years on the “Inconnu” (Stenodus leucichthys) and submitted the result as my masters thesis for the University of Saskatchewan. Convocation took place in early May.

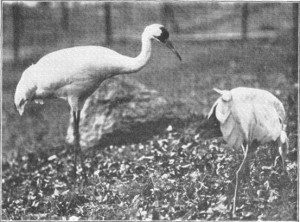

Whooping crane. (From a 1982 Hinterland Who’s Who brochure on the Whooping Crane written by E. Kuyt and published by the Canadian Wildlife Service)

A few days after the ceremony, I turned 23, and on the last day of May I married the young lady who is still my wife. I had previously applied for one of two jobs advertised by the federal government, and I was approved for the one based in Fort Smith, NWT. I found the north gets under your skin, and my wife Marie and I landed in Fort Smith on June 5. My duties centred on mammals in the south half of the Mackenzie District and in Wood Buffalo National Park (WBNP), part of which is in Alberta.In those days, the United States sent a bird guy, Bob Smith, and an assistant down to the Arctic Ocean. They flew out of Fort Smith for two or three days, and I usually took them up on their invitations to go on their sorties. Bob was a great guy, as well as a good pilot and a good bird man. Although waterfowl were the main target, they kept their eyes open for other birds, such as whooping cranes. As late as 1954 they had not made a sure discovery of whoopers, although on an earlier flight with them, one thought he had spotted a crane, but by the time Bob swung the plane around, whatever had been seen had disappeared.

In June 1954, a fire broke out in the northern part of Wood Buffalo Park. On June 30, the fire crew radioed to Fort Smith that one of their pumps was out of order. The forestry guy, George Wilson, went out to the site of the fire in a whirlybird piloted by Don Landells. I was in my office around 4:00 p.m. when a message came in from the plane to the effect that George and Don had seen a few big white birds, which they suspected were whooping cranes. Furthermore, Landells was to make another trip on the same route with a new pump, and if Bill Fuller was at the landing spot at 5:00 p.m he. could go back with Don and the pump.

Bill Fuller was at the landing and ready to go at 5:00 p.m. Don took us back on about the same route he had flown earlier, and we did see some large white birds, which were certainly whoopers. There were young birds as well as adults, so there was reason to believe that the nesting grounds were not too far away. I think we saw about nine birds on that first trip. I sent a telegram to the head office in Ottawa later that evening.

Ottawa’s reply the next morning asked me to keep an eye on the birds whenever there was a chance. I made several trips on an ordinary prop plane. On one such trip I counted thirteen birds, which was just over half of the birds (21, I think) counted in the Texas flock at that time.

The Whooping Crane Society and the USWS were very excited about the discovery, and soon there was talk about a ground survey in 1955. Canadian and American scientists would carry it out. However, the Canadian Wildlife Service (CWS) did not want to commit to that until there was proof of nesting, so I was to take a look next spring as early and as often as possible.

In those days, light aircraft landed on skis in winter and on pontoons in summer. The changeover was made in Edmonton in spring and fall, so it was difficult to find tansportation just when I needed it. While our government plane was in Edmonton, I got a ride with a pilot from Yellowknife on his way to Edmonton.I got another ride in a plane owned by the RCMP in Fort Smith. On that flight I saw what could only be a crane sitting on a nest. So the ground survey was on. Robert P. Allen of the National Audubon Society was to lead it. When Allen arrived in Fort Smith, we made one flight over the area so I could show him the location of the known nests.

The nesting habitat of the Whooping Crane consists of marshes, shallow ponds, small creeks, and patches of wooded terrain and shrubs. Note two whooping cranes in the center of the photograph.

I made other flights, and I think I found a few more nest sites, but when the ground survey came on, I was at a conference in Alaska. The attempted ground survey is a story of its own.In 1956 I moved to Whitehorse in the Yukon, and Ernie Kuyt of the CWS took over work on the cranes. I had flown over the region of the first sightings a number of times. I had noted the tracks in the mud and searched my brains for a mammal that would make such a trail in the soft mud of the lake bottoms. Big birds never crossed my mind until I saw the cranes there in 1955.So who discovered the nesting ground? Wilson and Landells, who saw the big white birds? Me, because I saw young birds as well as mature birds on my sorties in 1955 and was also the first to see a female on a nest in the spring of 1956?It doesn’t really matter. The important point is that an important nesting ground was found. Each year for several more years, Ernie Kuyt found new nests. The total number of cranes in the Texas/WBNP flock has continued to increase in most, if not all, years since 1955.b

* Published in Wild Lands Advocate, The Alberta Wilderness Association, December 2004 • Vol.12, No. 6, pages 16 and 17.

A WHOOPER NEW YEAR TO ALL

December 27, 2012by Chester McConnell

The Whooping Crane Conservation Association wishes Operation Migration, Florida, Louisiana, International Crane Foundation, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and all of our citizen supporters a Whooper Happy New Year. We hope for continued success of the several whooping crane programs. All our combined efforts are essential to help reach the goals described in the International Recovery Plan for the Whooping Crane.

Each private organization and agency has its own program but another very important element to the success of all programs is the tremendous contributions of the private citizens. They assist us in many ways including moral support, contributions of dollars, spreading the message and reporting observations. I want to give recognition to a special group of citizens who observe whoopers and take the time to report their sightings.

The Whooping Crane Conservation Association’s web site includes a “Report A Sighting” section where anyone can let us know about their observations of whooping cranes. We receive reports from many states and several provinces in Canada. While the vast majority of the reports are accurate a few actually turn out to be other large white birds with black wing tips (such as wood storks, white pelicans, snow geese, white ibis) or sand hill cranes. Mostly those who report their sightings have first gone to our web page “Identification” section to convince themselves that they have made a correct identification.

During the past year we have received about 130 reports of whooping crane sightings. About 100 reports involved birds from the Aransas/Wood Buffalo (Western) flock. These reports came from persons in 7 central states and 2 Canadian provinces. And about 30 were sightings of cranes from the Operation Migration (Eastern) program. These reports came from 12 eastern states. If a report seems questionable, we discuss the observations with those who made the report. We believe that about 90 percent of the citizen reports are accurate.

The information received is useful in monitoring the migration of the cranes and determining the locations of some of the individuals at a point in time. Of course some of the cranes are counted more than once because they move often during migration.

An added benefit from the citizen spotters is that some of them send us interesting photos and videos of their observations. We recently received an interesting video and some unusual photos from one of those wonderful people who report their observations of whooping cranes to us. I requested and received permission from Cindy P….. to share with you her video and photos of whooping cranes on her property in Georgia. Her email description of her experience follows:

“Hi Chester,

Of course you may use any of the photos/audio that I shared with you for your website.

On December 17, 2012 at about 7:30 am, one pair of cranes arrived near our 3 acre pond. They grazed and walked about the property and within the next hour another pair of cranes appeared. I grabbed my camera and lenses along with my iphone and headed towards the pond. The four birds casually walked around the pond nibbling here and there. They walked all the way up towards the pine trees where I was able to photograph them using a telephoto lens. I was careful not to get too close to them (you can see in the audio/video how far away they were) so that I wouldn’t scare them off. They continued calling and browsing around for a couple of hours. I was ecstatic!”

“The next two days, the cranes came in and stayed for about thirty minutes before they flew due south. I have to say that they were absolutely gorgeous and I only wish I could have gotten closer. I took a great photo of them flying away. I live about 2 hours from St. Marks, Florida. I think these birds belonged to the flock that migrates that way each year. Hope you enjoy the pictures as much as I did making them. Merry Christmas to all….

Cindy P…. GA

To observe Cindy’s video click on the following: https://www.dropbox.com/s/hei3j65ty422v5k/WhoopCranesCalling.MOV

Several of Cindy’s photos are pasted below. Enjoy.

Being very catious. 12-17-2012

Migrating on south. 12-17-2012

MORE PHOTOS, READ ON:

Now, you can enjoy more whooper photos from more of our citizen reporters by clicking on the fol;lowing link: https://whoopingcrane.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/Whooper-photos-8-for-web-article-11-29-124.pdf

Whooping Cranes from Despair to Hope to Progress

December 23, 2012*************History Briefs compiled by Whooping Crane Conservation Association************

The recorded history of whooping cranes has ranged from beliefs that the birds would become extinct to efforts to restore the flock. Whooping Crane Conservation Association member Pam Bates has researched the literature and come across some interesting material. Some of Pam’s findings are posted here for your interest:

Despair: The following is from the Gutenburg Project and dated 1913.

OUR VANISHING WILD LIFE ITS EXTERMINATION AND PRESERVATION BY WILLIAM T. HORNADAY, Sc.D. Page 19. “The Whooping Crane. —This splendid bird will almost certainly be the next North American species to be totally exterminated. It is the only new world rival of the numerous large and showy cranes of the old world; for the sandhill crane is not in the same class as the white, black and blue giants of Asia. We will part from our stately Grus americanus with profound sorrow, for on this continent we ne’er shall see his like again. The well-nigh total disappearance of this species has been brought close home to us by the fact that there are less than half a dozen individuals alive in captivity, while in a wild state the bird is so rare as to be quite unobtainable. For example, for nearly five years an English [Page 19] gentlemen has been offering $1,000 for a pair, and the most enterprising bird collector in America has been quite unable to fill the order. So far as our information extends, the last living specimen captured was taken six or seven years ago. The last wild birds seen and reported were observed by Ernest Thompson Seton, who saw five below Fort McMurray, Saskatchewan, October 16th, 1907, and by John F. Ferry, who saw

one at Big Quill Lake, Saskatchewan, in June, 1909. The range of this species once covered the eastern two-thirds of the continent of North America. It extended from the Atlantic coast to the Rocky Mountains, and from Great Bear Lake to Florida and Texas. Eastward of the Mississippi it has for twenty years been totally extinct, and the last specimens taken alive were found in Kansas and Nebraska. Photo was taken at “WHOOPING CRANES IN THE ZOOLOGICAL PARK ”

Hope: Two articles written by John O’Reilly in 1954 and 1955 issues of “Sports Illustrated” describe the extraordinary efforts of individuals, conservation organizations and government agencies to protect and manage the endangered whooping cranes. These two articles are posted below:

The surviving remnant of the great race of whooping cranes, hardly more than two dozen birds, will be “escorted” this fall from Canada to Texas. That is, they will be escorted insofar as it is possible for human beings to escort wild creatures which fly high and come to rest in lonely places. But, elusive though they may be, these huge white birds with the black wingtips will be followed on their route by thousands of well-wishers.

SPORTS ILLUSTRATED

Here Comes The Cranes, September 20, 1954

by John O”Reilly

The Survivors of America’s tallest birds will be “escorted” south

In advance of their coming a campaign is being conducted to alert the human population along the migration route of the cranes. As was the case last fall, radio stations will broadcast appeals to report the birds but not molest them. Their trip will be announced by newspapers. Sportsmen’s clubs and civic organizations have helped spread the word. Thousands of post cards bearing the facts and a picture of a whooper have been mailed to persons living along the flight lane.

All this is part of the international effort to help America’s tallest bird in its struggle for existence.

ONLY 26 ARE LEFT

When the birds migrated last spring there were 26 whooping cranes left—in the entire population of the species. Grus americana doesn’t occur in other parts of the world and they have been studied so thoroughly that the chance of even a single bird being discovered outside this group is highly improbable.

Two of the cranes, found crippled by gunshot, are now captives in a New Orleans zoo. The rest winter on the wide marshes and prairies of the 47,000-acre Arkansas Federal Wildlife Refuge on the Texas coast, 40 miles from Corpus Christi. There they live singly and in family groups, each family occupying a territory of some 500 acres from which other cranes are driven. Without the use of a blind it is difficult to get within half a mile of them. On a trip to the refuge I jeeped and stalked the prairies for days before I got a close view of the cranes. When a pair finally flew right over me I was told that I was luckier than most.

The exact location of the nesting grounds of the remaining whoopers has not been found. This summer a scientist hovering in a helicopter over the wild country south of Canada’s Great Slave Lake looked down and spotted four whooping cranes, three adults and a young one. His find was the best evidence so far of the general location of their breeding grounds.

The whooping crane once inhabited the central part of the continent from the Arctic Coast to central Mexico. It demanded plenty of space in which to live and rear its young, and when it stood at full height to utter its challenging buglelike call, it was almost six feet tall. But as the prairies were tamed and planted, the whooping cranes dwindled steadily.

PROJECT FOR SALVATION

Now the Fish and Wildlife Service, the Canadian Wildlife Service and the National Audubon Society are partners in a project designed to save the whooping crane from extinction. Numerous state agencies and private groups are cooperating. One of the prime workers on the project is Robert P. Allen, research ornithologist of the National Audubon Society. Allen devoted three years to an intensive study of the cranes, hoping to find a way to halt their decline.

During that time he lived with the birds on the lonely Texas marshes in winter. In early spring he took off by plane in advance of their migration and intercepted them along the Platte River in Nebraska. He traced their migration route through Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, the Dakotas and into Saskatchewan where they disappeared into Canada’s north country. He flew thousands of miles in the far north in a vain search for their nesting grounds.

People often ask how on earth the cranes know enough to go right to the refuge to spend the winter. The answer is that the presence of the whooping cranes there is historic and was one of the main reasons why the refuge was established in 1937.

As a result of Allen’s recommendations, numerous steps have been taken to aid the cranes. One of the main objectives has been to find the nesting grounds and learn whether there are any factors there which are limiting the increase. Canada has announced that when the nesting area is found it will be declared an inviolate sanctuary. Plans are now being made for a systematic search of the area next summer.

Each fall the refuge men are waiting eagerly as the cranes come back in little groups. By early December they are all in and the refuge men make an exact count by flying over them in small planes. In recent years the flock has returned with an average of four young birds. But usually a few of the parents are lost, some from being shot, and others from unknown causes. Sometimes the population fluctuates perilously. The gain or loss of a single bird is vital to the survival of the race.

Last year there was a gain. Twenty-one whoopers took off for the North in the spring and in the fall all 21 returned, bringing three gawky offspring with them. This fall more eyes than ever will be on the alert in the country’s most unusual bird-watching program.

SPORTS ILLUSTRATED

Whoop for Cranes – November 21, 1955 by John O’Reilly

Scientists who searched arduously and long for the nests of the all-but-extinct whooping crane rejoiced last week: its young are on the increase. Among birds, the all-but-extinct whooping crane is most symbolic of the mighty sweep of wilderness that once was America. Tall, wary and aloof, the whooping crane demands plenty of living space. It proclaims its utter freedom with a far-reaching, buglelike call. It regards the intrusions of man with an imperious look in its cold, yellow eyes. Although but a remnant of a once-great race, Grus americana seems imbued with a special urge to survive.

These are some of the reasons why the news of the return of 20 adult whooping cranes with a bonanza of eight young has just been greeted with such national exuberance. Last spring 21 whoopers left their wintering area on the Texas coast for their breeding grounds in northern Canada. By last Monday all except one adult were back in Texas. This bird may be lost or it still may be on the way. Sometimes the last migrants don’t get back until the first week in December.

A CAUSE FOR REJOICING

The appearance of eight young birds this year is cause for rejoicing among followers of the cranes both in the United States and Canada. The eight youngsters represent the largest crop since wildlife experts first started counting the remaining cranes 17 years ago. The largest previous number was seven young in 1939.

Anxiety over the migrating whoopers mounted steadily during the past two months as they made their 2,400-mile trip. Julian Howard, manager of the 47,000-acre Aransas National Wildlife Refuge near Austwell, Texas, has been swamped with demands for information on the returning whooper families. Never has the welfare of a migrating band of birds been of such concern to so many.

During the summer, workers on Project Whooping Crane, the international effort to keep the big birds flying, discovered the long-sought nesting ground of the last of the whoopers. As a result, it was known that the cranes had hatched at least six young.

Last summer, just as interest in the whoopers was reaching its height, the United States Air Force announced plans for establishing a photoflash bombing range within a mile of part of the birds’ wintering grounds. The National Audubon Society and local Audubon societies all over the country sent protests. More protests came from the National Parks Association, the United States Fish and Wildlife Service, the National Wildlife Federation, the American Nature Association and individuals who had helped in the struggle to save the cranes. Then the Canadian government made a verbal inquiry to the State Department. Last month the Air Force announced that its proposal to establish the bombing range had been withdrawn.

Old records show that whooping cranes once nested on the great prairies of the West and ranged over most of the country. Gradually they gave way before the plow and the gun, disappearing as their nesting grounds were settled and turned into wheat lands.

As long ago as 1923 some wildlife writers had declared the whooping crane extinct. The “last” nest had been found in Saskatchewan in 1922, and the young bird was taken from it, stuffed and placed in a museum. The existence of the wintering group on the Texas coast was known only to a few and it was their presence that led to the establishment, at that spot, of the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge. The big fight to save the whoopers started when Project Whooping Crane was set up 10 years ago.

The closest human associate of the whoopers since then has been Robert P. Allen, a square-built, black-haired Pennsylvanian. As research ornithologist of the National Audubon Society and leader in Project Whooping Crane, he had studied the cranes on their wintering grounds but his attempts to find their nesting sites in the far north had been fruitless. But, as he and others continued their work, public interest increased steadily.

The cause of the whooping crane became of such widespread interest that thousands of persons were on the lookout for them. Then in June 1954 some whoopers were spotted from a plane in Canada’s Wood Buffalo National Park, a wilderness area of 17,300 square miles, most of which is never visited by anybody, tourists or otherwise.

This knowledge led the international partners in Project Whooping Crane—the Canadian Wildlife Service, the’ U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Audubon Society—to launch an all-out effort to find the nests. Their aim was to discover whether anything or anybody was molesting the birds as they reared their young.

Allen was ready to start north to lead the expedition when William A. Fuller, biologist of the Canadian Wildlife Service, became the first man to see a wild whooper’s nest since that “last” nest was reported 33 years ago. Fuller was flying in the wild country along the Sass River on May 18 with Edward Wellien and Wesley Newcomb of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service when he spotted a pair of whoopers and a nest. On the same flight two more nests were seen.

This news spurred the expedition to action. Next to the actual finding of the nests the most important thing was to reach the area on the ground; to learn what, if any, were the dangers to the cranes; to study their nesting habitat and collect samples of their food. Allen hurried north and was met at Fort Smith, an outpost on the Slave River, by Raymond Stewart of the Canadian Wildlife Service and Robert E. Stewart, biologist of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Fort Smith is the jumping-off place for prospectors in the uranium rush. Men come and go and low conversations about uranium strikes are carried on in corners. So, as the three outfitted for their expedition, they were greeted with knowing smiles and sly smirks when they said they were heading into the bush to look for birds.

It was chilly on the morning of May 23 when the expedition set out down the mighty Slave River, which winds northwest to Great Slave Lake. At a great bend in the river, 44 miles from Fort Smith, they unloaded their supplies, cooked a meal and headed into the spruce forest. The Indian packers, two of them carrying the canoe, were strung out behind them. Nine hours later the three scientists said good by to the Indians and made their first camp on the shore of Long Slough.

As they moved down the slough the next morning in their overloaded canoe, the country around them was feeling the first touch of spring. Cattails were just beginning to show green. Canvasbacks, goldeneyes, buffleheads and other waterfowl were all about them. To the west they caught occasional glimpses of buffalo herds, with a spring crop of reddish-brown calves. They were still in high spirits when they made another portage, pitching their second camp on the banks of the Little Buffalo River. They moved up the Little Buffalo, still feeling fine. Turning into the Sass River, they rounded a bend to encounter their first trouble. It was a log jam, not of lumber logs but of trees and snags. They soon realized that the Sass was just one log jam after another, a fact that had not been apparent during their aerial survey.

They were sitting on the bank of the river, returning the stares of solemn buffalo and wondering what to do next, when they learned from their radio that they were believed lost and had become the objects of a search. The Northwest Mounted Police and park officials had been alerted. Unable to send out messages on their radio, they decided to strike for Fort Resolution on Great Slave Lake, where word of their safety could be sent out. After a turbulent trip down the Little Buffalo, they persuaded a Chipewyan Indian to carry a message across the frozen expanse of Great Slave Lake to Fort Resolution. Three days later Pat Carey, veteran bush pilot, dropped into the river mouth in his plane and took them back to Fort Smith. They were back where they had started.

A TRY BY HELICOPTER

Disappointment over their failure was forgotten on learning they could get the services of a helicopter which had been working north of Great Slave Lake. The helicopter transported them and their gear but, blown off course by a strong cross wind, the pilot became confused and dropped them 20 miles from where they thought they were landing. They didn’t realize this dismal fact until they had fought their way on foot for three days through swamps and sloughs.

Now they were really lost, and to make matters worse mosquitoes had emerged in millions, augmented by black flies, deer flies and a superdreadnaught called the bulldog fly. Their only relief from the clouds of insects came at night when they shut up their tent, killed the mosquitoes that were waiting inside and went to sleep.

At last, admitting they were licked, they put their canoe in the nearest river and started downstream. It turned out to be the Sass, the river of log jams. This time they cut their way through or portaged around 42 log jams, using the ax as much as the paddle. Reaching the Little Buffalo River, they went downstream and made the long portage back to the Slave River where a boat took them once more back to Fort Smith.

All told, they had been in the mosquito-infested woods for a month and hadn’t reached the home of the cranes. They had called the whole thing a failure and were ready to pull out when they learned another helicopter was available. Bob Stewart went back to Washington but Ray Stewart and Bob Allen prepared their gear for a third assault of the vast swamps.

This helicopter dropped them in the right spot and, as before, they started scouring the area on foot. Several days later Allen and Stewart emerged from a thicket to see a flash of white ahead of them. Slipping up, they came upon an adult whooping crane, drawn up to its full height of five and a half feet, silent and alert. Nearby was another. The two birds separated, finally moving out of sight. It was not until later that they learned this pair was hiding two offspring from them.

The goal had been reached. For 10 days the scientists studied the nesting habitat of the cranes. They collected specimens of frogs, fish, snails and other animal life which form the summer diet of the cranes. They also collected plant samples and made notes on everything that might have a bearing on the life of the whoopers.

Their work done, the helicopter ferried them out to the Slave River and they came up the river through the arctic twilight to Fort Smith in an outboard-driven skiff. Several days later I joined Bob Allen and Bill Fuller on a final aerial survey of the nesting area. As we moved over this watery world the scientists spotted two big, white birds. George Dannemann, our pilot, circled down to where we could tell they were whooping cranes. As the plane banked in a tight circle, we all saw not just the one, but two rusty-brown youngsters, two feet tall and standing between their white parents.

The scientists could restrain themselves no longer but began letting out whoops that would have done credit to the birds themselves. “Two young,” shouted Allen, and we all yelled in joy at just about the rarest sight that the bird world can offer in North America.

We saw two more fledglings on that flight and the scientists were jubilant. They and the thousands of others in the United States and Canada who are pulling for the whoopers know the cranes can never be brought back to their former numbers. But they also know that if Grus americana should disappear altogether it would mean the loss of something truly representative of the North American continent, for whooping cranes are nowhere else to be found.———End of O’Reilly article.

Voices from the Past: A 1954 recording of whooping cranes at Aransas. Pam Bates explains, “The Macaulay Library has 12 different whooping crane recordings but this one was my favorite because it talks about 1954 being the first year that they had 3 young whoopers that migrated with their parents from Canada. The whooping Crane population at Aransas was 24 that winter.”

Pam Bates advises, “The first speaker is Arthur Allen, a renowned ornithologist and who the Arthur A Allen Award is named after. Julian Howard, the second person to speak and mentions the annual count for 24 was the manager of Aransas at the time. Click on the link and follow:

ML: ML Audio 2739: Whooping Crane macaulaylibrary.org Finally, to hear the interesting Whooping Crane calls click on:

Unison (334kb wave)

Present: John O’Reilly was correct when he wrote in 1955 that “They and the thousands of others in the United States and Canada who are pulling for the whoopers know the cranes can never be brought back to their former numbers. But they also know that if Grus americana should disappear altogether it would mean the loss of something truly representative of the North American continent, for whooping cranes are nowhere else to be found. ”

Thank goodness that some of our government agencies and private conservation organizations continued to work to restore the whooping crane flock. The Whooping Crane Conservation Association has focused on this objective for over half a century. Very slowly during the past 57 years the flock has increased to approximately 300 in 2012. That’s progress by any measure.

Lobstick Whooper Remains A Mystery

December 21, 2012Editor’s Note: During April 2012 a whooping crane was murdered in the vicinity of Miller, South Dakota. At the time there was speculation that the dead crane was one of the famous Lobstick pair. The speculation continues. Captain Tommy Moore operates a tour boat in the vicinity of Aransas National Wildlife Refuge and believes he knows the Lobstick pair is alive. I contacted Tom Stehn retired Whooping Crane Coordinator to inquire. Luckily, Tom was going out the next day on Captain Moore’s boat and wrote me the following report. Chester McConnell, Whooping Crane Conservation Association, Web Administrator.

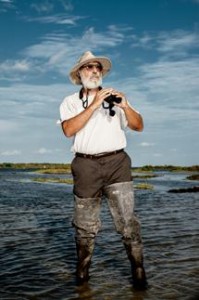

by Tom Stehn, Retired Whooping Crane Coordinator

On December 19th, I rode the whooping crane tour boat named the Black Skimmer to help with the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge’s Audubon Christmas Bird Count. Our group counted over 9,300 birds of 77 different species, but I didn’t see the bird I wanted to see most. The Lobstick whooping crane pair was not on its territory! We did spot 35 other whooping cranes, but I missed seeing what might be the oldest known aged whooping crane in the flock.

The Lobstick male was banded in 1978 as a 3-month-old chick in Canada’s Wood Buffalo National Park. After pairing up and successfully raising a chick in 1982, the Lobsticks continued their prolific breeding to become one of the most productive pairs in the flock. They have brought 17 chicks to Aransas in 31 years of nesting, and twice pulled off raising two chicks. Unfortunately, they have not made it to Aransas with a chick for the last three winters. The Lobstick male would now be 34, assuming he is still alive. His bands have fallen off, but voice printing multiple years ago of the male’s unison call had shown the same bird was present.

The pair continues to nest on Lobstick Creek just outside of Wood Buffalo National Park and defend the same territory on Aransas. They are often the first pair the whooping crane tour boats see. In the 2008-09 winter, the Lobstick male had difficulty flying for a spell, and the following winter we weren’t sure if he was present as the pair roamed more and was seemingly absent on several flights and boat trips. However, Captain Tommy Moore to this day continues to sight a crane pair on the Lobstick territory with a very large male that sometimes approaches the tour boat that could be Lobstick. Tommy thinks Lobstick is still alive. I don’t know for sure, but I’d like to think that 34-year-old old codger is still patrolling its Aransas territory as it keeps a glaring eye out for blue crabs and other cranes foolish enough to intrude on his territory. I didn’t see him the other day, but the refuge had recently done a prescribed burn, and I bet Lobstick had been on that upland area looking for roasted acorns. Other species of cranes have been known to live in captivity for over 80 years, so don’t count old Lobstick out.

Whooping Crane Conservation Association…working to conserve Whooping Cranes

December 16, 2012by Chester McConnell and Jim Lewis, WCCA

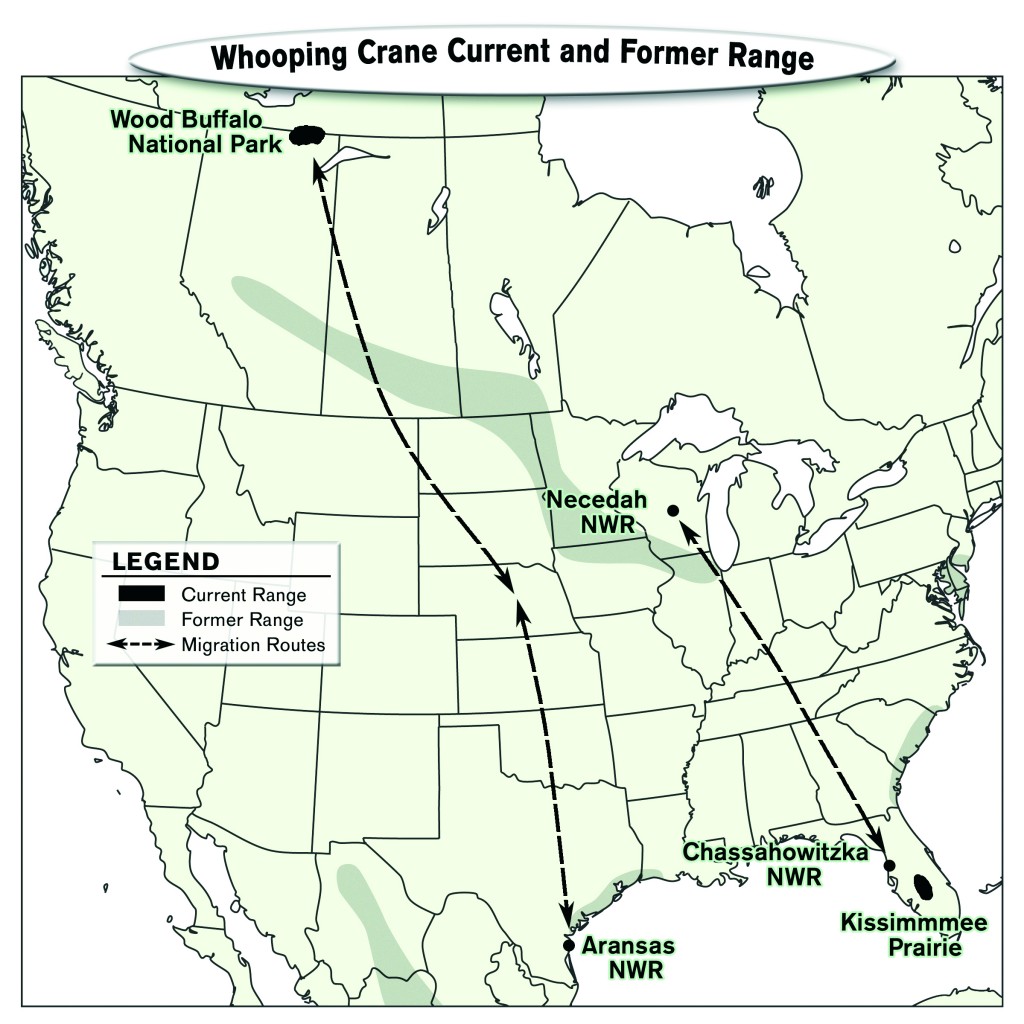

The Whooping Crane is the symbol of conservation in North America. Due to excellent cooperation between the United States and Canada, this endangered species is recovering from the brink of extinction. Their population increased from 16 individuals in 1941 to 588 wild and captive birds in September 2012. The name “Whooper” probably

came from the loud, single-note call they make when disturbed. The adult is 5 feet tall, the tallest bird in North America. When the wings are extended they are 7 feet from tip to tip. They are graceful flyers, elegant walkers, and picturesque dancers. Adults are a beautiful snowy white with black outer wing feathers visible when the wings are extended. The top of the head is red with a black cheek and back of neck, yellow eyes, and gray-black feet and legs.

Soft down covering the cute baby chicks is buff-brown. At about 40-days-of-age, cinnamon-brown feathers emerge. When they are one-year-old they have their white adult plumage.

Despite progress in increasing the numbers of these birds, only one population maintains its numbers by rearing chicks in the wild. This flock now contains about 300 birds that nest in Wood Buffalo National Park, in the Northwest Territory of Canada. They migrate to the Gulf Coast of Texas on Aransas National Wildlife Refuge and bordering private land where they spend the winter. It is on their wintering ground where they are especially vulnerable. A hurricane could destroy their habitat and kill birds, or an oil spill could destroy their foods. Less abrupt, but equally dangerous, is diversion of river waters that flow into the crane’s habitat. This fresh water is being used upstream for agriculture and for human uses in cities. The steadily diminishing flow into the Gulf of Mexico is making the area less productive for Whooping Crane foods. They need these foods to remain healthy, and to fatten for strength on their 2,500-mile migration and for producing young when they arrive in Canada where winter is just ending.

Whooping Cranes were once more abundant in the 1800s, nesting in Illinois, Iowa, the Dakotas, and Minnesota northward through the prairie provinces of Canada, Alberta, and the Northwest Territory. Drainage and clearing and of areas for farming destroyed their habitat, and hunting reduced their numbers. The only wild population that survived by the 1940s was the isolated one nesting in Northwest Territory. In March-April these cranes fly from Texas across the Great Plains and Saskatchewan to reach their nesting area.

They begin pairing when 2 or 3 years old. Courtship involves dancing together and a duet called the Unison Call. Whooping Cranes mate for life. Females begin producing eggs at age 4 and generally produce two eggs each year. Usually only one chick survives. The pair returns to the same area each spring and chases other cranes from their nesting area that is called a “territory”. It may include a square mile or a larger area. Chasing other cranes away ensures there will be enough food for them and their chick. At night they stand in shallow water where they are safer from danger.

They build a nest in a shallow wetland, often on a shallow-water island. The large nest contains plants that grow in the water (sedges, bulrush, and cattail) and may measure 4 feet across and 8 to 18 inches high. The parents take turns keeping the eggs warm and they hatch in about 30 days. The two eggs are laid one to two days apart so one chick emerges before the other. They can walk and swim short distances within a few hours after hatching and may leave the nest when a day old. The chicks grow rapidly. They are called “colts” because they have long legs and seem to gallop when they run. In summer, Whooping Cranes eat minnows, frogs, insects, plant tubers, crayfish, snails, mice, voles, and other baby birds. They are good fliers by the time they are 80 days of age. In September-October they retrace their migration pathway to escape winter snows and reach the warm Texas coast. During migration they stop periodically to rest and feed on barley and wheat seeds that have fallen to the ground when farmers harvested their fields.

In Texas they live in shallow marshes, bays, and tidal flats. They return to the same area each winter and defend their “territory” by chasing away other cranes. The territory may contain 200 to 300 acres. Winter foods are primarily blue crabs and soft-shelled clams but include shrimp, eels, snakes, cranberries, minnows, crayfish, acorns, and roots.

An individual bird may live as long as 25 years. But, Whooping Cranes face many dangers in the wild. Coyotes, wolves, bobcats, and golden eagles kill adult cranes. Bears, ravens, and crows eat eggs and mink eat crane chicks. When they are flying in storms or poor light they sometimes crash into power lines. And they die of several types of diseases.

In addition to the single self-sustaining population there are birds in captivity at seven locations and three other wild populations began as experiments to try to ensure that Whooping Cranes survive in the wild. There are 183 cranes in captivity including 23 young. Most of the young are released into the wild as part of the three experiments. In the first experiment, begun in 1993, juvenile captive-reared cranes were released in the Kissimmee Prairie of central Florida. Additional young cranes were released there each year. This is a cooperative effort by U.S. and Canadian federal agencies, the state of Florida and the private sector, to start a population that does not face the hazards of migration. Cranes learn a migration route from their parents. These cranes were raised in captivity so they did not learn to migrate. There were 87 cranes in this flock in 2003 including 7 adult pairs that successfully raised 3 young to flight age. Only 20 remain in 2012.

In 1997, Kent Clegg was the first individual to teach captive-reared Whooping Cranes to fly and follow a small aircraft. He led them in an 800-mile migration in the western United States. His technique was then used in the second experiment beginning in 200l to establish a population that nests in Wisconsin and migrates to western Florida. U.S. and Canadian federal agencies, provincial and state governments, Operation Migration, Inc., and other private sector groups are cooperating in this experiment. This flock now contains 104 cranes and others will be added in future years. The annual releases will stop when the two experimental populations produce enough young to maintain their numbers. Another non-migratory flock with 20 whooping cranes was established in Louisiana in 2011.

HOW YOU CAN HELP

You can help the endangered Whooping Crane recover its numbers so it can survive as a species. Join the Whooping Crane Conservation Association (WCCA) by clicking on: https://whoopingcrane.com/membership/ The WCCA is a nonprofit organization and your donations are tax deductible. The Association helps purchase habitat, fund research and management projects that aid Whooping Cranes and assists in educating the public about the dangers to this beautiful bird. As part of your membership, you will receive a handsome newsletter twice a year. The newsletter provides the latest information on status of the various populations, recovery progress, and other items of interest. ell others about the dangers to this bird and what is being done to benefit them.

WCCA’s web page at www.whoopingcrane.com includes current information, interesting facts and a coloring book for children.