Archive for the ‘Headline’ Category

Whoopers Continue On Their 2,500 Mile Migration

April 16, 2013by Chester McConnell, Whooping Crane Conservation Association

Approximately 50 to 60 percent of the whooping cranes have departed from Aransas Refuge (Texas coast) on their long 2,500 mile migration to Wood Buffalo National Park in Canada. Wood Buffalo is where they nest and rear their young. Dr. Wade Harrell, U.S. Whooping Crane Recovery Coordinator continually monitors the whooper flock on Aransas National Wildlife Refuge. Harrell described the ongoing migration of the birds as normal this spring. He explained that, “Whooping cranes are still being observed on the refuge, but the migration is well underway.

Harrell explained that, “As of Monday, April 8, 14 of the telemetry marked birds that we are actively receiving data on were still present on the Texas coast and 21 have begun migration. Based on this information and other observations, it is likely that greater than 50% of the birds in the Aransas/Wood Buffalo flock are currently migrating north. Of the 21 marked whooping cranes currently in migration, 14 are as far north as Nebraska and the Dakotas.”

Harrell estimates that most remaining birds will depart from Aransas Refuge over the next couple weeks. He advised that, “Whoopers are scattered along the migratory path as far north as North Dakota. Though the birds seem to be leaving in mass, they actually have staggered departures and leave in small groups. This is important as it ensures survival of the species. If they were to all leave together and encountered bad weather or some other catastrophic event, it could put the whole flock in jeopardy.” Dr. Harrell’s migration information mirrors information collected by the Whooping Crane Conservation Association (WCCA). Many bird watchers and a variety of citizens observe whooping cranes and report then on WCCA’s web page https://whoopingcrane.com/ .

Anyone who spots a whooper can go the web page and click on Report a Sighting and complete a simple form. WCCA places the information received on a map during the spring and fall migrations. Anyone can keep up with the migration by clicking on https://whoopingcrane.com/migration/ .

Migration Map

WCCA’s Migration Map includes all creditable whooping crane observations from reports received. Each whooper “icon” on the map represents from 1 to 6 birds. Observations have been posted on the Spring Migration 2013 map since mid-March. Importantly, all postings are delayed at least one week to help prevent harassment of the birds. Because the whoopers move frequently during migration, it is highly unlikely that one can use the map to locate the birds.

Water for Wildlife: The Fate of the Whooping Crane Depends on It

April 13, 2013by Melinda Taylor, University of Texas School of Law*

Texas is entering the third year of a drought that threatens to be worse than the 1950s’ drought of record. Across the state, the reservoirs that supply our towns and support industrial and agricultural demands are at alarmingly low levels, with no relief in sight.

The Texas Legislature is poised to create a fund to help finance conservation measures and new water infrastructure, an important step toward implementing the state’s water plan and ensuring that the water needs of the state’s growing population are met. The fund is the Legislature’s response to the economic impacts of the current water shortages: impacts on agriculture, recreation, and business.

But the drought has exacted a toll on the natural environment, too, causing harm to native and wildlife that is difficult to quantify. The shortage of rainfall has caused disruptions in the normal food chain, affecting everything from bats and birds to squirrels, raccoons, and white-tailed deer.

For the most part, impacts to wildlife take a back seat in the public’s mind to the ramifications for humans if the drought persists. But the interests of humans and wildlife often intersect and can sometimes collide, a point brought home by a federal court’s March 11 order to the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality to stop issuing water permits in the Guadalupe River in order to protect an endangered species on the Texas coast, the Whooping Crane.

On its face, the lawsuit appears to be yet another clash of endangered species versus humans, a Texas version of the spotted owl debate of the 1990s, or perhaps the latest example of federal impingement on Texas’s power to regulate its own natural resources. But, not surprisingly, the truth is more complicated. The reality is that the lawsuit was a last ditch effort to ensure that the Whooping Crane and the beautiful, resilient, finely tuned coastal ecosystem on which it depends can survive over the long run, even as the state grapples with the difficulty of meeting humans’ water needs during times of drought. The remedy ordered by the judge – that the state stop issuing permits to water users until it formulates a plan to protect the bird – is a common sense approach that should lead to a balanced state water permitting program.

The Whooping Crane is a majestic creature, the tallest crane species in North America and the rarest crane in the world. It is also an Endangered Species Act success story. In the 1940s there were fewer than 15 individual Whooping Cranes left in the world. Today, the population is estimated to be more than 500, with the world’s only self-sustaining wild population wintering in south Texas in and around Aransas National Wildlife Refuge. The Whooping Crane feeds on wolf berries and blue crabs, both of which suffer when San Antonio Bay becomes too salty, the result of inadequate freshwater flows into the bay. In 2009, scientists from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which manages the Refuge, noticed that Whooping Cranes were dying and appeared to be malnourished. They concluded that the birds’ food sources were literally drying up and that the only way to ensure their long term survival was to get more fresh water into the bay.

The Aransas Project, or “TAP,” was formed by conservationists, business owners, and landowners concerned about the Whooping Crane and determined to convince TCEQ to allow more water to flow down the Guadalupe River and reach the bay. They applied for a water permit with the intention of keeping the water they were allocated in the river, rather than pumping or diverting it, but the agency rejected the application. As a last resort, they brought suit under the federal Endangered Species Act, alleging that TCEQ was causing harm to the Whooping Crane by failing to ensure that sufficient freshwater reached the coast to maintain the crane’s food supply.

In December 2011, there was an 8-day trial during which the judge heard evidence from all the parties about all aspects of the case, including the Whooping Crane’s food requirements, the number of birds that live in Texas, and the State’s water permitting program and its ability to manage flows in the Guadalupe. The State and intervenors Guadalupe-Blanco River Authority and the San Antonio River Authority argued that a state law passed in 2009 set up a process by which the state would determine what flows are necessary to protect the state’s rivers, which precluded the need for federal action. But the court found a gaping hole in the state’s position: the state program on its face does not apply to existing water permits, only to new permits. Because the vast majority of water in Texas rivers and streams has been appropriated to water users already, it would be difficult, if not impossible, to secure sufficient flows to protect the Whooping Crane by relying solely on permit conditions in future permits. The court ruled in favor of the plaintiffs in the case and ordered TCEQ to devise a plan to protect the crane.

The Endangered Species Act contains a provision called an incidental take permit that authorizes otherwise lawful activities that cause harm to endangered species. To obtain a permit, a person (or state agency, as in this case) must prepare a “habitat conservation plan” to demonstrate that harm to the species will be minimized and mitigated “to the maximum extent practicable.” In this case, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has pledged to work with TCEQ to develop a plan to protect the Whooping Crane and its habitat in the course of administering the state’s water permitting program. The habitat conservation plan will fill the hole in the state’s program and provide an important safety net for the crane. Rather than resisting all federal involvement, TCEQ should cooperate with the Fish and Wildlife Service and figure out a creative way to ensure the long-term survival of this glorious denizen of the Texas coast.

* Senior Lecturer and Executive Director, Center for Global Energy, International Arbitration and Environmental Law, University of Texas School of Law

Whooping Crane Update – Aransas National Wildlife Refuge (summary)

April 12, 2013 by Wade Harrell, U.S. Whooping Crane Recovery Coordinator

by Wade Harrell, U.S. Whooping Crane Recovery Coordinator

Whooping Cranes on the Refuge:

Birds are still being seen on the refuge, but the whooping crane migration is well underway and we expect that most birds will depart the coast over the next couple weeks. Based on the tracking data and incidental observations, it appears that the birds using the periphery areas of the winter range (i.e. Lamar, Granger Lake, El Campo, Welder Flats) have been the first to depart this year. Though the birds seem to be leaving in mass, they actually have staggered departures and leave in small groups. This is important as it ensures survival of the species. If they were to all leave together and encountered bad weather or some other catastrophic event, it could put the whole flock in jeopardy.

Tracking Efforts:

As of Monday, April 8, 14 of the marked birds that we are actively receiving data on were still present on the coast and 21 have begun migration. Based on this information and other observations, it is likely that greater than 50% of the birds in the Aransas/Wood Buffalo flock are currently migrating north. Of the 21 marked whooping cranes currently in migration, 14 are as far north as Nebraska and the Dakotas

Taking a look into the past as we consider the future:

The following graphic shows the expansion of wintering whooping cranes on and around the Refuge over the past 55 years (1951-2006). As we have seen this winter, this expansion has now moved to a few inland locations such as the Granger lake area. This trend gives us hope that the species will continue on the upward trend. To read the full report, click on: http://www.fws.gov/nwrs/threecolumn.aspx?id=2147517593

Water, Whooping Cranes, and the ESA

April 5, 2013by Dave Owen, Associate Professor of Law, University of Maine School of Law*

Three weeks ago, a federal district court in Texas issued an important ESA decision. The Aransas Project v. Shaw also is a very long decision—124 pages, to be exact—so I’ve been a bit slow to get a blog post up. Despite its daunting length, the case is important reading for anyone interested in water management or the ESA. It’s also a rather intriguing case study of the use—both successful and badly botched—of expert testimony in environmental litigation.

The case arises out of water management controversies in Texas. According to the plaintiffs, the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality and its fellow defendants had taken whooping cranes in violation of section 9 of the Endangered Species Act. They had done this, the plaintiffs argued, by allowing excessive water withdrawals from the river systems that feed into the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge, which provides vital whooping crane habitat. The court agreed, enjoined the issuance of new water permits, and ordered the defendants to prepare a habitat conservation plan and seek an incidental take permit.

The case arises out of water management controversies in Texas. According to the plaintiffs, the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality and its fellow defendants had taken whooping cranes in violation of section 9 of the Endangered Species Act. They had done this, the plaintiffs argued, by allowing excessive water withdrawals from the river systems that feed into the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge, which provides vital whooping crane habitat. The court agreed, enjoined the issuance of new water permits, and ordered the defendants to prepare a habitat conservation plan and seek an incidental take permit.

That’s a very interesting outcome, because successful section 9 actions against water managers don’t seem to be particularly common. I haven’t done any sort of rigorous survey, but my impression, based on working as a water lawyer and then on my academic research into related ESA questions, is that environmental groups have gained much more leverage through ESA section 7. Indeed, in the Southeast’s longstanding Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint controversy, similar take claims brought against upstream water managers failed. See Alabama v. Army Corps of Engineers, 441 F. Supp. 2d 1123 (N.D. Ala. 2006) . So could this case signal the emergence of a new front in the ESA/water allocation wars? My suspicion is that several factors will make these plaintiffs’ success difficult to replicate. In no particular order, those factors are:

The extraordinary level of data available to the plaintiffs in this case. Reading the opinion made me wonder if these whooping cranes are one of the most carefully observed wild animal populations on earth. As the court describes, scientists have been counting whooping cranes since the 1950s. Since the early 1980s, scientists—including one of the plaintiffs’ experts—have conducted dozens of monitoring flights every year. The resulting level of information is exceptional. Usually population biologists must rely on some combination of observational data (usually limited), proxy indicators like habitat conditions, and computer-based modeling to assess the status of a population. The resulting uncertainties can limit plaintiffs’ ability to demonstrate causal relationships with enough certainty to support a successful ESA section 9 claim. With whooping cranes, the circumstances are quite different.

The imbalance of experts. The plaintiffs had an impressive array of experts on their side. Here’s the court’s description:

At trial, TAP presented seventeen witnesses, ten of whom were experts, GBRA eight; SARA one: and TCEQ two. As will be discussed in more detail later, TAP’s experts were world renowned in their respective fields. Several of TAP’s witnesses hold endowed chairs at prestigious universities, some are MacArthur Fellows, all have published numerous scientific papers in respected journals. Indeed, one witness, Dr. Ronald Sass, is a shared recipient of the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize for his environmental work. TAP’s crane experts… have years of study in the field and have devoted their time and energies to the survival of the AWB species. All of TAP’s experts were accepted as such and the Court finds their testimonies compelling and credible.

The court had less laudatory things to say about the defendants’ experts. For example:

Dr. Slack did not personally spend any significant amount of time in the field, averaging one day per year over the past fifteen years. Contrary to the scientific literature, Dr. Slack testified that cranes did not need freshwater because they had functioning supraorbital salt glands which allowed them to secrete excess salt. However, when questioned further by the Court, Dr. Slack admitted that he had no observational basis for this statement, he had not reviewed literature on cranes and freshwater, and that he “just made it up.” (record citations omitted)

The level of judicial interest. From the outset, the narrative structure of the opinion (yes, it does have a narrative structure) strongly suggests that someone in the court’s chambers cared very deeply about this case, and probably also about whooping cranes. Before getting into the procedural history, relevant law, or even the identities of the parties, the opinion spends several pages describing the whooping crane die-off, much like a detective novel beginning with the key murder. But the real tip-off comes later, in a remarkable passage debunking the work of one of the aforementioned Dr. Slack’s graduate students:

[A key defense report] used a report by Dr. Slack’s graduate student Danielle Greer whose conclusions to the preferred food of whooping cranes was (sic) based on 90 plus hours of video of three crane areas. The Court watched all of the videos and finds that they were either too blurred to see anything or non-demonstrative of any habit, feeding or otherwise.

So what does this all suggest? If I’m reading correctly, it shows that when plaintiffs have extraordinarily good monitoring data, an all-star team of experts, poorly prepared experts on the other side, and a judicial chambers where someone—perhaps the judge, more likely a clerk—cares so deeply that she is willing to watch 90 hours of blurry footage of whooping cranes, they can win an ESA section 9 case against upstream water managers. Absent those circumstances, the challenge might be a bit harder. That doesn’t mean there won’t be other cases like this. Conflicts between water withdrawals and the needs of endangered fish and wildlife probably aren’t going away any time soon. But the case does illustrate the level of scientific and legal work necessary for plaintiffs to prevail.

* Dave Owen’s article is re-posted from Environmental Law Prof Blog, A Member of the Law Professor Blogs Network

MY SOAPBOX

April 1, 2013Editor Note: This exceptional article by Joe Duff is posted with permission of Operation Migration. Joe has a way with words as well as flying ultralight planes to lead young whooping cranes on their first migrations. The article is a lesson that should be read by all who venture onto wild lands and encounter wildlife. Please read and pass it on. Thanks Joe and O.M.

by Joe Duff, Operation Migration, Mar. 27, 2013

Earlier this month Fox 13 News in Tampa Bay posted an article about two photographers who overstepped the line of ethical wildlife observation by handling a two week-old Sandhill crane chick. They were captured on film and now wildlife officials say they could face charges if they can be found.

People do a lot worse to animals than handling their offspring, and although it is not condoned, that’s not the interesting part of this story. What is more telling is the mixed reactions posted in the comments section. Some people feel the perpetrators should be shot for their transgressions while others think they had every right to play with a baby bird.

The most common reaction is that maybe they didn’t know they were not allowed to handle wildlife. That excuse was also suggested when Whooping cranes were shot by kids showing off to their girlfriends. Many people commented that if the shooters had known what they were, or if more education was available, those birds wouldn’t have been shot — with a high powered rifle — on private property — at night. If that was a valid defence you could simply say, “Sorry I burned your house down. I didn’t know I wasn’t allowed to”. Ignorance of the law is not a defence, it is simply ignorance – not only of the rules but also of our responsibility to nature.

The fact that we even need laws at all is evidence of how we view our relationship with the environment. If we truly appreciated the connection between nature and ourselves, rules to protect it would be as unnecessary as a law against destroying our own wealth.

The planet, in all its complexity is the producer of everything we have, the materials we use to build our society, the water we drink, even the air we breathe. There is no other source for those essentials yet we use them as if they were inexhaustible. We are the prodigal heirs of a rich family. We did nothing to create the prosperity and we lack the ability, or the motivation, to maintain our inheritance, yet we spend the wealth with no concern for the future. But the environment was not inherited from our grandparents, More accurately it is borrowed from our grandchildren.

So what does it matter that a photographer in Florida handled a Sandhill chick to get a better picture when cranes are hunted in some states? It matters because it demonstrates how little we care about the creatures around us. Through his willingness to ignore the rules, he chose his own gratification over the welfare of the chick. Whether it was a desire for a better photograph or simple curiosity, he threatened the life of that bird for his own benefit. His ignorance of the consequences is as inexcusable as his ignorance of the law.

For those who think no harm was done, you don’t understand the stress load on the parent. A crane may abandon their chicks if the threat is too great. Instinct tells them it is better to escape and reproduce again next season than to be injured defending a chick that will perish as a result. If the chick is lost, the adult will survive, but if the adult is injured, they will both die.

As for the chick, they are vulnerable at that age. They hatch neither tame nor wild but have a natural fear of the unfamiliar. Most of their wildness is learned from the parent. An adult bird will remain wary despite several encounters with people, but a chick can become complacent after only one. Despite our good intentions, tame birds have a far shorter life span that their wild counterparts.

The point is, that all creatures are part of the ecosystems that make the world work. Damaging them even slightly, can have long term consequences that at some point will affect our lives. If we want to protect our future, we must learn to respect nature, even the baby Sandhills.

Bob Hunter, one of the founders of Green Peace, once said, “Conservationists are a pain in the ass, but they make great ancestors.”

http://operationmigration.org/InTheField/2013/03/27/my-soapbox/

Transmitters allow Crane Trust scientists to follow whooping cranes during migration

March 21, 2013Posted with permission of KearneyHub.com

By LORI POTTER Hub Staff Writer , Posted: Friday, March 8, 2013 2:00 pm

Whooping Crane Tracking Partnership

Whooping crane

A juvenile whooping crane wears a transmitter with a global positioning system that identifies its location four times daily for researchers at the Crane Trust near Alda and along the Central Flyway from Texas to Canada. There now are transmitters on 35-40 of the 279 migrating whooping cranes. Rick Rasmussen, Platte River Photography Crane Trust officials are asking the public to assist with Whooper Watch during the spring migration season. Adult whooping cranes are white with black wingtips. Visit the website at www.nebraskanature.org for details.

ALDA — Whooping cranes wearing solar-powered transmitters tell researchers at the Crane Trust near Alda and throughout the Great Plains states and Canadian provinces where the birds stop during spring and fall migrations.

But it’s still up to scientists on the ground to fill in the details.

“Where we’re taking a leading role is evaluating the stopover locations on the Central Flyway,” said Crane Trust Director of Science Mary Harner.

“It’s a big thing in science now,” Crane Trust Wildlife Biologist Greg Wright said about tracking wildlife with global positioning systems, “but it only goes so far … So you have to be there.”

Wright and other biologists go to the GPS-identified stopovers to make detailed surveys of the land cover and other habitat features, and to talk to landowners. “Teams are scattered (throughout the flyway), so someone always is relatively close and you can get there in good time,” he said.

The Whooping Crane Tracking Partnership began in 2008 as a research project conceived byCrane Trust staff, with support from U.S. GeologicalSurvey, to use a transmitting system to identify migration pathways.

Data gathering started in 2009 when the first whooping cranes were captured at wintering areas at Aransas National Wildlife Refuge in south Texas and breeding sites at Wood Buffalo National Park in Canada. The captures were authorized by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Canadian Wildlife Service.

Each captured bird is given a health check. Platform transmitting terminals with GPS systems and antennas are attached to their legs.

Harner said Neoprene is used on the inside of the devices as a cushion between them and cranes’ legs.

There are solar panels on the three exposed surfaces of the two-piece leg bands to maximize recharge of batteries that are expected to have a lifespan of three to five years.

Wright said there now are 35 to 40 whooping cranes with transmitters. “This technology was thoroughly researched on sandhill cranes before it was used on whooping cranes,” he added.

Harner said the project has collected a little over half of the location data that is expected over the duration of the research. The Crane Trust website says researchers expect to follow the birds in the field through 2015.

A February 2013 USGS report for the five core project partners — the others are the Crane Trust, Canadian Wildlife Service, Platte River Recovery Implementation Program and USFWS — summarizes the project’s history and data from 2012.

Location data was gathered for 36 whooping cranes during the 2012 summer breeding season in

Canada. During last fall’s migration, 261 stopover locations were documented, including one east of Lexington, one east of Kearney and one east of Wood River.

The report says 11 adults and one juvenile whooping crane were captured at Aransas this winter and the plan is to capture 10 more adults during winter 2013-2014. It also says that during the project’s lifetime, the goal is to have transmitters on about 30 juvenile (hatch-year) birds and 30 adults.

The project goals listed by the five core partners in a 2011 research partnership document are to advance knowledge of whooping crane breeding, wintering and migratory ecology; disseminate research findings for conservation, management and whooping crane recovery; and minimize negative effects of research activity on the cranes.

Other organizations supporting the project are the Gulf Coast Bird Observatory, International Crane Foundation and Parks Canada.

“Partners agree that this opportunity to mark wild whooping cranes with GPS technology represents the best prospect in the past 30 years to enhance understanding of whooping cranes and assess risks they face during their entire life cycle,” the USGS report says.

Wright said the cooperation of landowners where whooping cranes have been spotted has been a wonderful asset to the research.

“We’re certainly learning things,” he said, but the data collected so far is a small sampling of what researchers will have in the next year or two. “There’s really not a precedent for this.”

Harner said transmitters are activated immediately after they are placed on the cranes and are programmed to record four GPS locations daily, once every six hours.

There is a time lapse because transmitters upload new data approximately every 2½ days. Researchers are dispatched to survey the places where it’s known that whooping cranes have been.

Wright said that once the signals are downloaded, a decoding program must be used “so it means something to us.”

“Project partners monitor the whooping crane location data closely as the project continues,” Harner said, “and we will be working together over the next several years to continue collecting, processing and analyzing the data, and sharing research findings.

“Far-reaching partnerships make this landmark study successful, and we look forward to ongoing collaborations to advance our understanding of this magnificent species.”

email to: [email protected] ________________________________________

WHOOPING CRANE FACTS, Whooping Crane (Grus americana)

Features: Tallest bird in North America, at 5 feet. Mostly white with black wingtips and face, and red head.

Numbers: Approximately 280 in a migratory flock that breeds in Wood Buffalo National Park in Canada and winters at Aransas National Wildlife Refuge in south Texas. In captivity or part of re-introduction efforts, 290.

History: There are accounts of whooping cranes seen during spring and fall migrations since European settlers arrived in Nebraska in the 1840s.

Lowest numbers: Due to hunting and habitat loss, only 15 birds remained in 1941.

Recovery challenges: Loss of habitat, altered wetlands, climate change and collisions with power lines.

Breeding: Whooping cranes normally lay two eggs, with one egg-chick surviving. Adult pairs have been seen with twins, including five sets arriving at Aransas in 2010.

Behaviors: Territorial at breeding and wintering grounds, and use the same areas year after year.

Migration route: About 2,500 miles long and 300 miles wide through Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, South Dakota, North Dakota, Saskatchewan and Alberta.

Critical habitat: Four sites designated in the 2005 International Recovery Plan for the Whooping Crane are Salt Plains NWR in Oklahoma, Cheyenne Bottoms State Waterfowl Management Area and Quivira NWR in Kansas, and the Platte River between Lexington and Denman. ________________________________________

Whooper watchers still sought

ALDA — Crane Trust officials are seeking public help to spot endangered whooping cranes during their spring migration through Nebraska in March and April.

If you see a whopping crane, call Whooper Watch at 888-399-2824 to report the time, exact location, crane numbers and activities.

A scientist will be sent to confirm the sighting and document location features.

Do not disturb the birds. Stay in a vehicle or established viewing area at least 2,000 feet (0.4 of a mile) away. Don’t tell others of the sighting or location to avoid attracting more attention.

There are only about 280 whooping cranes in the wild flock that winters in south Texas and goes to summer breeding grounds in Canada’s Prairie Provinces. During their 2,500-mile spring and fall migrations, they may stop for one to several days along the Platte or other Nebraska rivers and wetlands to rest and feed.

Visit the website at www.nebraskanature.org to download a flyer that includes bird identification information and Whooper Watch rules and procedures.

Big Win For Whooping Cranes

March 12, 2013Editor’s Note:After three years of waiting, the court has made its decision on the case, “The Aransas

Project vs. Bryan Shaw, et al.” The result is a tremendous victory for endangered whooping cranes and their habitats. In summary, too much fresh water was being removed from upstream sources and whooping crane habitats downstream, on and around the Aranasas National Wildlife Refuge, was being robbed of an equitable share of fresh water. This has had, and is continuing to have, a severe adverse effect on whooping cranes.After reading the “Introduction” and the “Memorandum Opinion and Verdict of the Court”, we decided to post it here verbatim because it is written in such a clear and concice manner. And you will have the facts as the court had written them. For those wanting to read the entire court decision, click on: http://thearansasproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/TAP-Opinion.pdf

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT, SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS,CORPUS CHRISTI DIVISIONTHE ARANSAS PROJECT, Plaintiff, VS. BRYAN SHAW, et al., Defendants.

INTRODUCTION.

In the annals of conservation, the return of the Whooping Crane from the brink of extinction is one of the most fabled stories. In the 1940’s, less than fifteen of these remarkable birds – the tallest in North America and the rarest species of crane in the world – remained. With the creation of wildlife refuges and other conservation efforts, the population of the birds has slowly risen to, including both those in captivity and those not in captivity, to around 500 birds. At issue here is the threat of extinction to the non-captivity population of around 300. However, the “whoopers” are still at risk, as development and environmental issues continue to threaten their habitat.

This case concerns the world’s only self-sustaining, wild Whooping Crane population, known as the “AWB” flock, and its winter home in South Texas at the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge (the “Refuge”), and surrounding estuarine areas that comprise the AWB cranes’ critical winter habitat. The AWB cranes normally begin to arrive at their winter habitat in late October, and depart in early April of the following year.

The Aransas Refuge is located midway along the Texas Gulf coast, about 140 miles southof Houston and 50 miles north of Corpus Christi. The cranes’ wintering grounds are comprisedof approximately 9,000 hectares of salt flats on the Refuge itself and also on adjacent islands,including the Blackjack Peninsula, San Jose Island, and Matagorda Island.

The area is bordered on the east by the Gulf of Mexico, receiving daily impulses of salt water with the changing of the tides. The Refuge receives freshwater inflows from primarily two river sources, the San Antonio and the Guadalupe, each located to the north and slightly west of the area.

The San Antonio river flows into the Guadalupe river system, and the Guadalupe river flows directly into the Refuge, emptying into the San Antonio bay. The area where the freshwater enters the Refuge is referred to correctly as the “Guadalupe estuary,” but it is known also as the “San Antonio bay.” The San Antonio and the Guadalupe river systems emerge from underground springs near San Antonio and run 250 miles southeast where they join together just before entering the San Antonio bay and flow into the AWB flock’s winter habitat, that extends slightly north of the Refuge.

These freshwater inflows come from a combination of spring flows and rainfall. Whooping Cranes face extinction. Indeed today, it is estimated that only 500 Whooping Cranes exist worldwide. In 1967, the United States listed the Whooping Crane as threatened with extinction, 32 Fed. Reg. 4001 (Mar. 11, 1967), and in 1970, they were listed as endangered 35 Fed. Reg. 16047 (Oct. 13, 1970). In 1973, both of these classifications were “grandfathered” into the Endangered Species Act. 16 U.S.C. § 1531, et seq., 87 Stat. 884.

Beginning in 1950, the United States Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS) employed aerial surveys to provide an annual census of how many AWB cranes arrived at the Refuge in the fall, and how many departed in the spring. Mr. Tom Stehn, a USFWS biologist, worked at the Refuge for over 29 years, and personally developed and implemented a method to count the individual birds of the AWB flock utilizing the cranes’ well-documented behaviors of site fidelity, site tenacity, and crane territoriality.0 Because specific birds returned to their specific locations, Mr. Stehn was able to map their territories and to confirm their presence or absence with weekly aerial surveys. Based on his intimate knowledge of the AWB crane and his mapping of their territories, Mr. Stehn concluded that, at the start of the 2008 winter season, the AWB flock had grown to its peak number of 270 birds, plus or minus 2 to 3 percent.

During the 2008-2009 winter, there was a severe drought. As the winter progressed, the AWB cranes began to demonstrate unusual behavior. For example, parents would deny their juveniles food, and the birds began venturing out of their specific territories in search of food and fresh water. When the cranes first arrive at the Refuge, it is normal for the parents to feed the juvenile. The juveniles’ beaks are soft and tender, and it is necessary for the parent to break the shell and feed the crab to the begging juvenile. As the winter progresses, the parent pulls the crab from the water, kills it, and leaves it for the juvenile. During the 2008-2009 winter, Dr. Chavez Ramirez observed a parent aggressively pushing his juvenile away from a crab that had been caught. He had never seen a parent deny food to a begging juvenile. Such behavior indicates that the parent was under food stress. The birds’ behavior was so alarming that Mr. Stehn contacted Dr. Chavez-Ramirez, a biologist with two decades of field research on the AWB cranes and a member of the International Whooping Crane Recovery Team, and asked him to visit the Refuge and observe the cranes. Dr. Chavez-Ramirez was equally troubled and concerned with his observations of the cranes’ behavior. Both he and Mr. Stehn observed that the lack of freshwater inflows had increased salinities across the Refuge. These hyper-saline conditions, verified by field measurements, led to a decrease in blue crabs and wolfberries, the staple diet of the AWB flock. This food shortage led to bird emaciation, stress behavior, and an over-all decline in bird health. That is, without proper freshwater inflows, the AWB’s critical habitat had been thrown out of balance, with ramifications up and down the food chain. That winter, at least 23 AWB cranes, or 8.5 % of the AWB flock, died at the Refuge. Another 34 birds that left Texas in spring, failed to return in fall.

After news of the high crane mortality in the 2008-2009 winter became known, certain environmentalists, local coastal business owners, bird enthusiasts, and others formed “The Aransas Project,” (“TAP”), a Texas nonprofit corporation. The TAP members have a direct interest in the AWB Whooping Cranes and the ecological health of the San Antonio, Carlos, Mesquite, and Aransas bays that connect to the Refuge.

The State of Texas owns its surface water, and this includes the water in the Guadalupe and the San Antonio River systems. Under Texas law, freshwater capture and use is regulated by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ), a State agency. Through its permit process and regulatory powers, the TCEQ can affect the availability of freshwater to users along the river system.

Prior to filing this lawsuit, TAP petitioned the TCEQ for a water permit to require a certain amount of freshwater to remain instream in the Guadalupe and San Antonio river systems to ensure that sufficient amounts of freshwater reached the Refuge and surrounding areas adjacent to the San Antonio bay that comprise the critical habitat of the AWB cranes. TAP’s permit request was denied, and on December 7, 2009, TAP gave notice of its intent to sue.

On March 10, 2010, TAP filed this lawsuit alleging that the TCEQ defendants had violated Section 9 of the Endangered Species Act (ESA), 16 U.S. C. § 1531 et seq., by failing to properly manage freshwater inflows into the San Antonio and Guadalupe bays during the 2008-2009 winter, causing an unlawful “take” of AWB cranes. (D.E. 1). TAP maintains that the TCEQ defendants’ water management practices during 2008-2009, combined with the severe drought, drastically modified the AWB cranes’ critical habitat making it hyper-saline. In turn, the hyper-saline conditions caused a reduction in the availability of wolfberries and blue crabs, the cranes’ primary food resources, as well as in fresh drinking water. The lack of food and freshwater caused the cranes to become emaciated and to engage in stress behavior. Emaciation led to increased illness and disease susceptibility, and the cranes’ unusual stress behaviors including leaving the safety of their site territories, contributed to increased predation. In total, the adverse modification of the cranes’ critical habitat effectively caused the death of at least 23 Whooping Cranes that winter season, constituting a “take” under the ESA.

MEMORANDUM OPINION AND VERDICT OF THE COURT

Thus, it is therefore DECLARED that:

(1) The TCEQ, its Chairman, and its Executive Director have violated section 9 of the ESA, and continue to do so through their water management practices which include the decision to not monitor D&L users or to exercise emergency powers available to protect the endangered whooping cranes; and

(2) Texas water diversion regulations promulgated by the TCEQ, its Chairman, its Executive Director, and the Texas legislature are preempted by federal law when they purport to authorize water diversions that result in a taking of whooping cranes.

Therefore, it is ORDERED that:

(1) The TCEQ, its Chairman, and its Executive Director are enjoined from approving or granting new water permits affecting the Guadalupe or San Antonio Rivers until the State of Texas provides reasonable assurances to the Court that such permits will not take Whooping Cranes in violation of the ESA.

(2) Within thirty (30) days of the date of entry of this Order, the TCEQ, its Chairman, and its Executive Director shall seek an Incidental Take Permit that will lead to development of a Habitat Conservation Plan. See 16 U.S.C. § 1539(a); 50 C.F.R. § 17.22(b) (listing requirements for an Incidental Take Permit)

The Court will retain jurisdiction over this action during the formulation of the HCP process. The Court finds that Plaintiff TAP is the prevailing party in this matter, and is entitled to an award of its reasonable attorney’s fees and costs, as well as expert witness fees, incurred in this action. See 16 U.S.C. § 1540(g)(4).

SIGNED and ORDERED this 11th day of March, 2013. Janis Graham Jack Senior United States District Judge

The Whooping Crane Conservation Association appreciates the decision made by U.S. District Judge Janis Graham Jack and the work of James Blackburn, everyone on The Aransas Project team, Tom Stehn and other private citizens who made our voices heard! This is a tremendous decision in favor of endangered whooping cranes and other wildlife along the Texas coast that need and deserve their share of fresh water.

Winging it 2,500 Miles to Rear Their Families

March 9, 2013by Chester McConnell, Whooping Crane Conservation Association

Some whooping cranes are heading north. They are departing from Aransas Refuge on the Texas coast. They’re on their way to Canada’s Wood Buffalo nesting grounds 2,500 miles away. Only a small number from the Aransas/Wood Buffalo flock have departed from Aransas but others will soon follow. According to Dr. Wade Harrell, U.S. Whooping Crane Recovery Coordinator: “It appears that some whooping cranes have started to migrate back north, which is several weeks earlier than normal. Perhaps this is not surprising given the unusually warm and dry winter that the southern plains have experienced.”

March brings restlessness to the wintering cranes as days get longer. Cranes of the Aransas/Wood Buffalo flock could encounter dangerous cold and stormy weather if they move north too rapidly. But, whoopers heading to Canada must race for their nesting grounds where summers are short. Adult pairs have to build a nest, lay two eggs and incubate the eggs for 30 days when the chicks hatch. Then they must feed the chicks large amounts of food to get the youngsters ready for the long migration back to Texas. So, whoopers have much to do in a short time on the nesting grounds. Hopefully the northern habitats will be thawed and ready for nesting when they arrive. Most of the Wood Buffalo nesting area is still currently frozen. But whooping cranes are wise and the migration to Canada normally requires 40 to 60 days.

So most likely icy conditions will change before most of the cranes arrive there.Yet, whoopers are definitely in their migration mode. Citizen whooper watchers have reported birds in northern Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas and Nebraska. Eight whoopers were reported as far north as North Platte, Nebraska. Migration records kept by the Whooping Crane Conservation Association indicate about two dozen birds along the migration route. Some of these observations have been verified by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service refuge managers.

Hopefully all the whooping cranes currently on the way to Canada and those waiting on Aransas Refuge, Texas will have a safe 2,500 mile migration. We know that, sadly, two members of this flock will not be with them. They were shot and killed during the past year, one by a poacher (South Dakota) and the other by a hunter (Texas). Both of the men who killed the whoopers have been prosecuted and received large fines and other punishment. The Whooping Crane Conservation Association urges state and federal wildlife agencies and birding organizations along the migration route to increase their efforts to educate hunters and other citizens about the compelling need to help protect endangered whooping cranes.

Interestingly, Dr. Harrell’s “Wintering Whooping Crane Update” report (3/7/2013) described the movements of one whooper family that has GPS transmitters attached to them: “Update February 24: The marked family group (two adults and one juvenile) from Granger Lake left arriving in North Texas that evening. They stayed through Feb. 28 and then moved to SW Oklahoma where they remained through March 2. They then moved on to Quivira National Wildlife Refuge in South Central KS, a traditional migration stopover site for whooping cranes, where they currently remain.”

More about whooping crane migration can be learned by reading The Whooping Crane Tracking Partnership’s recently issued biannual report. The following is a summary of the data captured from the 2012 breeding season through fall migration (approximately May through November). Background information about the Partnership can be found on the following link: https://whoopingcrane.com/tracking-whooping-cranes-telemetry-update/

Excerpts from the report: “During the 2012-2013 season, information was gathered about location from 36 transmitters during the breeding season and data from 30 transmitters during fall migration. Prior to migration, six transmitters stopped providing data. With the help of the technology, the mortalities of two juveniles and two subadults were confirmed on the breeding grounds of Wood Buffalo National Park. The two other transmitters were confirmed to have broken antenna. The tracking technology also revealed that three cranes spent the summer months in south-central Saskatechewan and 29 marked birds completed the fall migration.”

“The birds began their fall migration from Canada on September 7, 2012, and data indicates that all of the birds arrived on the Texas coast by November 27, 2012. It took the cranes an average of 46 days to make the migration with the migration time ranging from 21 to 67 days. The data shows whooping cranes used 261 different locations where they stopped and stayed for more than one night. Stopover locations occurred in every state and province in the Great Plains. Cranes spent the most time at staging sites in Saskatchewan and the Dakotas. The general migration corridor used was similar to past migrations and there were no mortalities detected during the migration.”

“The GPS tracking devices attached to the whooping cranes are programmed to record four locations daily and provide both daytime and nighttime locations. Transmitters upload data approximately every 2.5 days allowing for monitoring survival. The technology allows biologists to learn which habitats are being used and where the birds stop during their migration – important information when prioritizing management decisions.”

The Whooping Crane Conservation Association supports the Whooping Crane Tracking Partnership’s in hopes that the information they collect will help in the improved management of the whoopers.

Dallas Man Convicted and Fined for Killing Whooping Crane

March 7, 2013by Chester McConnell, WCCA

Worthey D. Wiles, 42, of Dallas, has entered a plea of guilty and was sentenced for killing a whooping crane .Wiles killed the whooping crane on January 12, 2013. The announcement was made by United States Attorney Kenneth Magidson today along with Nick Chavez, special agent in charge of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS).

Wiles was a guest hunter at the St. Charles Bay Hunting Club in Rockport which is located inside the designated critical habitat for whooping cranes. While hunting in the marsh adjacent to San Jose Island, Wiles shot and killed a juvenile whooping crane. After contacting Texas Parks and Wildlife (TPW), Wiles told state game wardens he thought the whooping crane was a Sandhill crane. Wardens then contacted FWS who located the bird and verified it was a whooping crane.

Even though Wiles believed he was shooting a Sandhill crane, hunting for them is illegal near San Jose Island where the bird was killed and throughout the whooper’s traditional wintering habitat centered on the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge north of Rockport.

“The whooping crane is one of the most beautiful and highly valued species of America’s wildlife heritage,” said Chavez. FWS is committed to protecting this extraordinary bird so that future generations of Americans are able to marvel at its grace and beauty.”

Wiles, a Dallas duck hunter shot and killed one of the juvenile cranes that had hatched and been reared by its wild parents during the summer of 2012 on Wood Buffalo, Canada nesting grounds. The young whooping crane was one of only 34 produced in Canada in 2012 and was killed during its first visit to the Texas coast. It had successfully completed its first 2,400 mile migration from Canada to Texas. Young whoopers have a potential life span of 40 or more years if they remain healthy. The Whooping Crane Conservation Association asserts that even the loss of one crane from the approximate 300 wild whoopers in the world is a serious tragedy.

Whooping cranes are one of the rarest birds in the world with a total population of approximately 437 cranes in the wild and 599 overall. The whooping crane population that winters in Texas is the only self-sustaining wild population of whooping cranes in the world. This case is only the fifth known shooting death of a whooping crane since 1968. Killing one of the approximate 300 wild whooping cranes that migrate from Canada to Texas is a federal violation of the Endangered Species Act. Punishment spans a broad range of fines, restitution fees and prison terms. Under the federal Endangered Species Act it is a crime to harm, harass or kill a federally-protected species. Violators face fines of up to $250,000 and up to one year in jail.

Today, when Wiles appeared before United States Magistrate Judge B. Janice Ellington, he entered a plea of guilty to one count of violating the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, which provides protection for Migratory Birds. As a result, he was ordered to pay a $5,000 fine and make a $10,000 community service payment to the non-profit organization Friends of Aransas and Matagorda Island National Wildlife Refuges. He will also serve a one-year-term of probation for his conviction. The Whooping Crane Conservation Association stated it is pleased that a $10,000 community service payment is going to Friends of Aransas and Matagorda Island National Wildlife Refuges. The organization performs valuable voluntary services for the refuge.

In a recently settled case, a South Dakota man who shot and killed a whooping crane was ordered to pay $85,000 in restitution and serve two years’ probation. He was also required to surrender his firearms used in the offense and will lose his fishing, hunting and trapping privileges anywhere in the United States for two years and pay a $25 assessment to the Victim Assistance Fund. A Whooping Crane Conservation Association spokesman said restitution should be a minimum of $150,000 based on the amount of time, effort, research, land costs, law enforcement and other expense that goes into nurturing and protecting these iconic birds. Likewise, the Association believes jail time should be imposed on violators to let it be known that such crimes are serious.

The Aransas County death is the fifth known Texas case involving the shooting of a whooping crane since 1968, though another crane death in Calhoun County remains under investigation. Previous Texas cases from 1989 and 1991 ended in fines totaling $21,000 and $23,100 respectively.

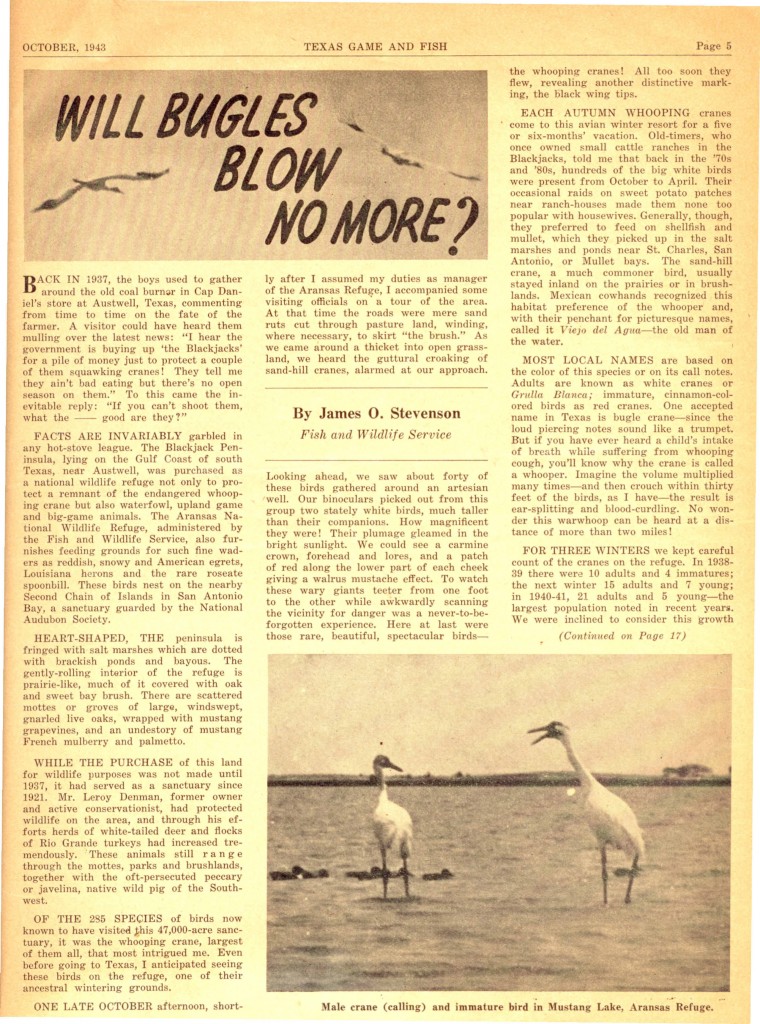

Will Bugles Blow No More?

March 4, 2013Editor’s note: Pam Bates, historian with the Whooping Crane Conservation Association, enjoys searching old files for interesting information about whooping cranes. We have posted several of her finds on this web page for your information and reading pleasure. Pam recently located an article titled “Will Bugles Blow No More?” written by James Osborne Stevenson in the Texas Game and Fish newsletter.

James Osborne Stevenson became the first refuge manager of the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge in Texas under the Bureau of Biological Survey. There he spent much of his time observing, studying, and photographing whooping cranes. He took the first ever color films of their courtship dances, and published a number of scientific and public interest articles on these cranes. In 1943, he published an article called Will Bugles Blow No More? about their endangerment. Jim died of a stroke on October 14, 1991.

If you have problems reading the article, double-click on the articles to enlarge the print.