by Chester McConnell and Jim Lewis, WCCA

The Whooping Crane is the symbol of conservation in North America. Due to excellent cooperation between the United States and Canada, this endangered species is recovering from the brink of extinction. Their population increased from 16 individuals in 1941 to 588 wild and captive birds in September 2012. The name “Whooper” probably

came from the loud, single-note call they make when disturbed. The adult is 5 feet tall, the tallest bird in North America. When the wings are extended they are 7 feet from tip to tip. They are graceful flyers, elegant walkers, and picturesque dancers. Adults are a beautiful snowy white with black outer wing feathers visible when the wings are extended. The top of the head is red with a black cheek and back of neck, yellow eyes, and gray-black feet and legs.

Soft down covering the cute baby chicks is buff-brown. At about 40-days-of-age, cinnamon-brown feathers emerge. When they are one-year-old they have their white adult plumage.

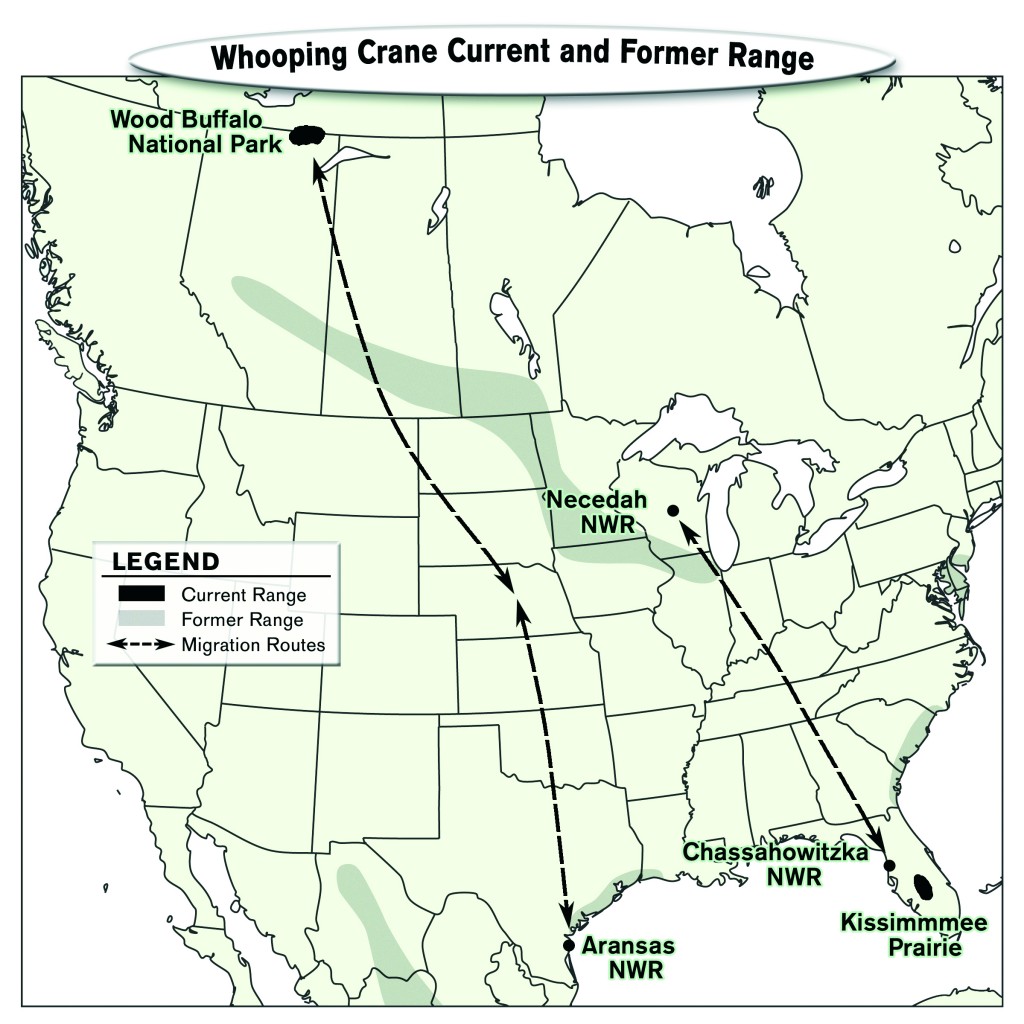

Despite progress in increasing the numbers of these birds, only one population maintains its numbers by rearing chicks in the wild. This flock now contains about 300 birds that nest in Wood Buffalo National Park, in the Northwest Territory of Canada. They migrate to the Gulf Coast of Texas on Aransas National Wildlife Refuge and bordering private land where they spend the winter. It is on their wintering ground where they are especially vulnerable. A hurricane could destroy their habitat and kill birds, or an oil spill could destroy their foods. Less abrupt, but equally dangerous, is diversion of river waters that flow into the crane’s habitat. This fresh water is being used upstream for agriculture and for human uses in cities. The steadily diminishing flow into the Gulf of Mexico is making the area less productive for Whooping Crane foods. They need these foods to remain healthy, and to fatten for strength on their 2,500-mile migration and for producing young when they arrive in Canada where winter is just ending.

Whooping Cranes were once more abundant in the 1800s, nesting in Illinois, Iowa, the Dakotas, and Minnesota northward through the prairie provinces of Canada, Alberta, and the Northwest Territory. Drainage and clearing and of areas for farming destroyed their habitat, and hunting reduced their numbers. The only wild population that survived by the 1940s was the isolated one nesting in Northwest Territory. In March-April these cranes fly from Texas across the Great Plains and Saskatchewan to reach their nesting area.

They begin pairing when 2 or 3 years old. Courtship involves dancing together and a duet called the Unison Call. Whooping Cranes mate for life. Females begin producing eggs at age 4 and generally produce two eggs each year. Usually only one chick survives. The pair returns to the same area each spring and chases other cranes from their nesting area that is called a “territory”. It may include a square mile or a larger area. Chasing other cranes away ensures there will be enough food for them and their chick. At night they stand in shallow water where they are safer from danger.

They build a nest in a shallow wetland, often on a shallow-water island. The large nest contains plants that grow in the water (sedges, bulrush, and cattail) and may measure 4 feet across and 8 to 18 inches high. The parents take turns keeping the eggs warm and they hatch in about 30 days. The two eggs are laid one to two days apart so one chick emerges before the other. They can walk and swim short distances within a few hours after hatching and may leave the nest when a day old. The chicks grow rapidly. They are called “colts” because they have long legs and seem to gallop when they run. In summer, Whooping Cranes eat minnows, frogs, insects, plant tubers, crayfish, snails, mice, voles, and other baby birds. They are good fliers by the time they are 80 days of age. In September-October they retrace their migration pathway to escape winter snows and reach the warm Texas coast. During migration they stop periodically to rest and feed on barley and wheat seeds that have fallen to the ground when farmers harvested their fields.

In Texas they live in shallow marshes, bays, and tidal flats. They return to the same area each winter and defend their “territory” by chasing away other cranes. The territory may contain 200 to 300 acres. Winter foods are primarily blue crabs and soft-shelled clams but include shrimp, eels, snakes, cranberries, minnows, crayfish, acorns, and roots.

An individual bird may live as long as 25 years. But, Whooping Cranes face many dangers in the wild. Coyotes, wolves, bobcats, and golden eagles kill adult cranes. Bears, ravens, and crows eat eggs and mink eat crane chicks. When they are flying in storms or poor light they sometimes crash into power lines. And they die of several types of diseases.

In addition to the single self-sustaining population there are birds in captivity at seven locations and three other wild populations began as experiments to try to ensure that Whooping Cranes survive in the wild. There are 183 cranes in captivity including 23 young. Most of the young are released into the wild as part of the three experiments. In the first experiment, begun in 1993, juvenile captive-reared cranes were released in the Kissimmee Prairie of central Florida. Additional young cranes were released there each year. This is a cooperative effort by U.S. and Canadian federal agencies, the state of Florida and the private sector, to start a population that does not face the hazards of migration. Cranes learn a migration route from their parents. These cranes were raised in captivity so they did not learn to migrate. There were 87 cranes in this flock in 2003 including 7 adult pairs that successfully raised 3 young to flight age. Only 20 remain in 2012.

In 1997, Kent Clegg was the first individual to teach captive-reared Whooping Cranes to fly and follow a small aircraft. He led them in an 800-mile migration in the western United States. His technique was then used in the second experiment beginning in 200l to establish a population that nests in Wisconsin and migrates to western Florida. U.S. and Canadian federal agencies, provincial and state governments, Operation Migration, Inc., and other private sector groups are cooperating in this experiment. This flock now contains 104 cranes and others will be added in future years. The annual releases will stop when the two experimental populations produce enough young to maintain their numbers. Another non-migratory flock with 20 whooping cranes was established in Louisiana in 2011.

HOW YOU CAN HELP

You can help the endangered Whooping Crane recover its numbers so it can survive as a species. Join the Whooping Crane Conservation Association (WCCA) by clicking on: https://whoopingcrane.com/membership/ The WCCA is a nonprofit organization and your donations are tax deductible. The Association helps purchase habitat, fund research and management projects that aid Whooping Cranes and assists in educating the public about the dangers to this beautiful bird. As part of your membership, you will receive a handsome newsletter twice a year. The newsletter provides the latest information on status of the various populations, recovery progress, and other items of interest. ell others about the dangers to this bird and what is being done to benefit them.

WCCA’s web page at www.whoopingcrane.com includes current information, interesting facts and a coloring book for children.