Archive for the ‘Endangered Species’ Category

Young Whooping Crane In Capture Project Dies

September 3, 2012 |

|

Young whooping cranes, 31 in all, have been banded with transmitters for three summers in their summer Wood Buffalo National Park habitat. (Photo: Courtesy of Parks Canada)

|

A juvenile whooping crane has died, possibly from a self-inflicted wound suffered trying to escape capture in Wood Buffalo National Park. The bird was to be banded as part of a program attaching radio transmitters to juvenile cranes. The carcass has been shipped to the Canadian Cooperative Wildlife Centre in Saskatoon for autopsy.

“We don’t know the cause of death. The crane was injured. It may have happened as part of the capture process,” Stuart McMillan, Wood Buffalo National Park manager of Resource Conservation told The Journal.

Crews land in a helicopter and try to round up the young birds, which naturally run away. McMillan said cranes are known to scratch themselves while running.

The bird was seen to be injured after it was captured for the banding process. A veterinarian is part of the capture crew and the young bird was examined immediately, treated with an antibiotic and released. It returned to its parents and things seemed normal. Some time later, the signal from the transmitter stopped moving. On investigation, the bird was found dead.

“It is certainly disappointing. We didn’t want to have a result like this. We want to find out what happened to prevent it from happening again,” said McMillan.

He said if the cause of death is from the capture process they will study it and make changes to procedures to minimize the risk of it happening again.

The banding exercise, called “telemetry,” is a joint Canada-US project. Thirty one juvenile cranes have been outfitted with transmitters over the last three years without incident.

Migration routes, habitat sought during migration, food sources and threats cranes face are just some of the information the project hopes to gather. The data is still preliminary, and it is too early to draw conclusions.

It is known that whooping cranes often stop in the same places year after year as they come and go annually between Aransas Wildlife Refuge in Texas and Wood Buffalo National Park in the NWT. In some places where they are known to stop each year, people gather to watch for them. It is hoped that public awareness can be raised once more is learned about where and when they stop.

One thing being investigated is the impact of power lines. Dead cranes have been found in the vicinity of power lines but no one knows why. Some speculate lines should be marked along the migration route and that new lines planned in those locations be erected at different sites. One benefit of the radio transmitters is that a dead bird can be found right away.

“When a crane dies it is best to look at an intact carcass to determine the cause of death, not one decomposed or torn apart by scavengers. If banded with a transmitter which stops moving, we can go look for the bird right away,” said McMillan.

This winter, adult birds will also be captured and banded at the Aransas Wildlife Refuge.

Tracking Whooping Cranes – Telemetry Update

September 1, 2012Article courtesy of Crane Trust

The Crane Trust continues to gain momentum in their efforts to contribute to conservation and the preservation of the whooping crane and other migratory birds. The Whooping Crane Conservation Association applauds their work and believes viewers of our web page will appreciate reading one of their recent reports. The following is an excerpt from Crane Trust’s July-August newsletter.

The Crane Trust is one of five research groups involved in a remote-tracking study of whooping cranes in the world’s only self-sustaining flock—the Aransas-Wood Buffalo population, comprised of fewer than 300 cranes. Findings from the study will help the Trust and its partners better understand the ecology and threats to whooping cranes on their wintering grounds, breeding grounds, and their 2,500-mile migration route through the Central Flyway. Twice each year, the Whooping Crane Tracking Partnership publishes an update on its progress and findings. For the two latest reports on progress and findings, click downloads below. Above photo courtesy of Michael Sloat.

2011 Fall Report DOWNLOAD (2011 summer breeding/fall migration)

2012 Spring Report DOWNLOAD (2011-2012 winter season/spring migration)

You can download the two most recent reports at the end of this summary. Of note, the study’s research team has improved its methods of trapping and continues to catch and mark young and adult whooping cranes with GPS transmitters on both breeding and wintering grounds. For each bird, the solar-powered transmitters provide up to 4 signals a day for the life of the device (3-5 years). In the winter of 2011, that amounted to more than 11,000 locations for tracking and analysis. To read the entire article click on following link: http://www.cranetrust.org/newsletter/july-august-2012/tracking-whooping-cranes-in-space-and-time%E2%80%94telemetry-update/

Journey North Whooping Crane Info

August 25, 2012Journey North produces one of the most interesting web pages that I am aware of. It is a prime educational tool for teachers and appeals to nature interests of all ages. Recently Journey North posted some very interesting information concerning Whooping Cranes and the Seasons, The Annual Cycle of the Whooping Crane. We wanted our viewers to be aware of Journey North’s information and we pasted their post in hopes it will be easier for you to open. We invite you to click on the “blue links” below to observe some excellent photography and associated information about whooping cranes.

Chester McConnell, Web Page Editor, Whooping Crane Conservation Association

Whooping Cranes and the Seasons Whooping Cranes and the SeasonsThe Annual Cycle of the Whooping Crane More Slideshows |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Whooping Crane Man

July 23, 2012by Michael Berryhill , a Texas Monthly article, August 2012

No one knows more about whooping cranes than Tom Stehn, who studied and cared for them for three decades. Then he retired—only to discover that the magnificent and endangered birds needed him more than ever.

Early last December, Tom Stehn was enjoying his retirement in Aransas Pass, soaking in his hot tub after a morning of windsurfing, when the phone rang. He grimaced for a moment but hopped out of the water naked to see who was bothering him. A U.S. marshal was calling from his car, which was parked in Stehn’s driveway. A federal judge in Corpus Christi wanted him to testify about the deaths of 23 whooping cranes he’d reported during the winter of 2008 to 2009, two years before he had retired. The marshal asked if Stehn could come to court immediately. “All right,” he said, “but give me a minute to put on my clothes.”Stehn knew what the case was about. A longtime biologist for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, he had served as its whooping crane coordinator for over a decade. No one had more hands-on experience with the birds, which are among the most endangered in North America. He had flown on countless aerial surveys to identify the whooping cranes’ winter territories in the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge, studied their habitat, measured the salinity of their marshes, celebrated their return each year, nurtured their sick, and, when he could, recovered their dead. In the winter of 2008 an emaciated juvenile had died in his arms.

Over the years, Stehn had watched the flock grow from 71 to nearly 300 birds. But he determined that during the drought of 2008 and 2009, 8.5 percent of the wintering flock and nearly 45 percent of the first-year juveniles had died. The following year, coastal tourism businesses, environmentalists, and the O’Connor family of Victoria, who owns tens of thousands of acres near the Guadalupe River, formed a nonprofit group called the Aransas Project and sued the state. The organization claimed that, under the Endangered Species Act, the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) was responsible for the deaths of the cranes because it had failed to allow enough freshwater to flow from the Guadalupe River into San Antonio Bay, which adjoins the wildlife refuge.

The State of Texas, led by the Guadalupe–Blanco River Authority (GBRA), countered that the lawsuit was based on pure speculation. Of the 23 birds that Stehn had reported dead, only 4 carcasses had been recovered. How could he prove the others had died? And even if they had, how could the environmentalists know that the deaths resulted from a lack of freshwater? Witnesses for the state contended that computer models proved the whooping cranes could survive perfectly well with very little freshwater. They even claimed that because of a special gland, whooping cranes might not need to drink freshwater at all.

The case has exposed a long-simmering battle between the two sides. Although state law directs the TCEQ to plan for freshwater inflows to keep Texas bays healthy and productive, environmentalists have been complaining for years that the agency has failed to live up to its responsibilities. In 2003, for example, a group of environmentalists had applied for water rights to protect wildlife in San Antonio Bay, and the TCEQ denied the request. The GBRA, in particular, has a great deal at stake. Its priorities are cities, farmers, and industry, and there are plans for several new power plants, including a proposed nuclear facility, to be built in the region. If the plaintiffs win, those projects could be put on hold.

Both parties had visited Stehn’s old office and obtained copies of his annual reports, and both had tried to recruit him as a paid expert witness. Though the Department of the Interior typically prohibits its biologists from testifying as expert witnesses, Stehn was inclined to stay out of the trial anyway. He had been concerned about the management of the Guadalupe River for years, and he worried that the state’s lawyers would try to destroy his life’s work to win the suit. U.S. district judge Janis Jack decided that Stehn’s testimony was essential, however, and she ordered each side to pay half of his $200-an-hour fee. “That’s good Christmas money,” the judge told him.

Since this was a bench trial, the case hinged primarily on whether Jack believed Stehn’s testimony. It was as if he were the only eyewitness at a murder trial and the victims were his children. Still, his presence did provide a bit of levity. Because his last name rhymes with the birds’ name, the judge would laugh when lawyers on both sides addressed him, in slips of the tongue, as “Mr. Crane.”

“I know these cranes,” he told the court. “I’ve been watching some of the same ones since 1982. I hate to be—what’s the word?—anthropomorphic, but it’s almost like they’re my kids out there.”

Of the fifteen species of cranes in the world, Stehn explained, only the whooping crane is territorial about its winter grounds. Mated pairs, some with juveniles they have reared during the summer in Canada, stake out an average of 425 acres of coastal marsh along the peninsulas and barrier islands of San Antonio Bay. When these territories were first mapped, in the late forties, there were only fourteen. As the flock grew over the years, the birds claimed smaller pieces of marsh, and by the winter of 2008 to 2009, Stehn had identified seventy different territories. Because the birds always returned to the same place, Stehn believed his weekly aerial surveys would allow him to count every crane. (The Lobstick territory had been used by the same male crane for thirty years.) He finally concluded that the flock had grown to 270 birds, plus or minus 2 or 3 percent.

After Stehn explained his census methods, Jim Blackburn, a veteran environmental attorney from Houston who was leading the case for the Aransas Project, asked the kind of question that lawyers hate: one whose answer they’re not absolutely sure of. He needed to know how many cranes had died that winter. “Is twenty-three your number?” he asked.

Stehn took a long moment to think about his response. Blackburn felt his gut turning over, because this was the heart of the case. Stehn noticed a look of puzzlement, almost panic, in Blackburn’s face and then said, “If I had to pick a number, it would be higher than twenty-three.”

The dead included mated pairs that had not had offspring as well as pure-white parents with rusty juveniles. But Stehn had also been watching ninety subadults, who tended to move about the refuge. “They can be on the refuge one day, they can fly across the bay to San José [Island] the next day or the next hour . . . they can be singles,” Stehn testified. “So you can’t ever tell if a bird like that is missing. It’s very reasonable to assume that some of them died that are not in that twenty-three.”

As for the 23 Stehn was certain had died, he could identify each by territory and date. Because the deaths had occurred all across the refuge, he believed that drought was the culprit. “It was a high-mortality winter,” Stehn said, “and at that point, the food supply was not good. There were low numbers of crabs, and the wolfberry crop had not been good. And from my experience, that kind of screams out that trouble is brewing.”

The refuge staff started feeding the cranes shelled corn at thirteen stations on upland parts of the cranes’ winter grounds, but this created a different problem. The birds are safest from predators in the open marsh, but when they fly inland, they increase their chances of being attacked by bobcats and other predators. To follow up on Stehn’s testimony, the environmentalists needed to prove that the lack of freshwater inflows was also related to the deaths. Two Rice University professors presented data that linked low river inflows to high crane mortality.

The GBRA fought back with a $2.14 million study it had helped fund in 2002 called the San Antonio Guadalupe Estuarine System, or SAGES, to determine the effect of freshwater inflows on whooping cranes. The report, which was released in 2009, around the same time that Stehn had reported the deaths of the cranes, concluded, “None of the study results indicated that habitat conditions [at the refuge] are marginal for crane survival and well-being.” The SAGES scientists built a conceptual computer model that indicated there was plenty of food, regardless of conditions.

During the testimony, Jack freely interrupted lawyers and questioned witnesses. She wrote notes furiously and researched suspect statements. At the outset of the trial she cracked, “I just wanted to rule out the fact that those [missing cranes] could have gone to New Mexico or, you know, to Antigua for the holidays or something.” Most of her remarks were aimed at the defense. She often shut down lines of questioning that seemed tiresome with a terse phrase: “Got it.” During eight days of testimony, the state heard that a lot.

A defense witness who reviewed the necropsy of one of the four crane carcasses noted that the bird had a greenish discoloration of the leg, which he associated with gangrene. Jack was astounded. She was well aware that gangrene is typically associated with a blue or black discoloration, so she grilled him about other weaknesses in his testimony. “I’m sorry,” she told the courtroom. “I know I’m being difficult with him, but I have never heard a scientist say when he saw something green that he thought of gangrene. I can’t quite move beyond it.”

Jack was even harder on R. Douglas Slack, the Texas A&M professor who led the SAGES study. Slack’s researchers had concluded that insects, clams, snails, and acorns would provide enough nutrition for the cranes, basing their findings in part on eighty to ninety hours’ worth of sometimes fuzzy videos that recorded the feeding habits of the birds. Stehn had presented Texas Parks and Wildlife Department data that showed that the cranes’ favored food, blue crabs, declined during times of low river inflow.

Jack grew exasperated with the SAGES model and its failure to incorporate the diet and mortality data that Stehn had collected. Under her intense questioning, Slack conceded that the cranes probably did need freshwater inflows—even if the model said they didn’t.

“Okay,” Jack said. “I’m just telling you, you can’t create a model. You can’t create a multiplier based on no information, which is what you’ve done. You have done it on what you figure is a normal, walking-around bird without determining how much energy it takes to forage for this versus forage for that. All these different things are critical to the well-being of the whooping crane. Even I can figure that one out.”

Slack’s most embarrassing moment came when the judge pressed him about the cranes’ supraorbital salt gland, which the defense claimed made them immune to the high salinity that comes with drought.

“I’ll tell you,” Jack said, “when the report was filed, I said, ‘What is this, a natural desalinization plan?’ So I looked it up, and there wasn’t anybody that ever described any such thing on a whooping crane.”

At one point, Jack asked Slack, “Where did you get that?”

“I don’t know,” he replied.

“You just made it up?”

“Yeah, I just made it up.”

After eight days of testimony, Jack heard no final arguments but instead asked each side to file briefs. She has encouraged both sides to work toward a settlement while she reviews the testimony, but if they cannot reach an agreement, she could issue a verdict as early as this month. If Jack rules for the Aransas Project, she could order the state to negotiate a Habitat Conservation Plan, in which the state would apportion the cranes a share of freshwater from the Guadalupe River. Bill West, the general manager of the GBRA, said that such a ruling would overturn traditional Texas water rights that date back more than one hundred years and disrupt the economic growth of the middle coast of Texas. “There’s no question,” he said. “It’s a classic example of federal intervention into state water rights by use of the Endangered Species Act. The judge does not have the authority to interfere with state water rights.”

In the meantime, Stehn has returned to Aransas Pass and to windsurfing, soaking in his hot tub, and enjoying the peace and quiet. But he laments how his old job has changed. During last year’s record drought, the remains of three cranes were recovered, but the total number of deaths was difficult to determine. That’s because biologists now employ a technique known as distance sampling to estimate the size of the flock. The new method, which is widely used to determine the populations of rare and endangered wildlife, doesn’t count birds individually, as Stehn used to do. Instead biologists fly aerial surveys during a predetermined time frame, and the cranes that are identified are recorded as a percentage to determine the population. However, according to guidelines, the two observers in the plane are not allowed to tell each other if one sees a bird. Nor does the pilot return, as Stehn did, and fly over a particular area again and again to search for missing birds in specific territories.

Stehn always believed that the results of his census were 97 to 98 percent accurate. He has read that the new method for estimating the birds is only 85 percent accurate. He thinks that between thirty and forty cranes could have died last winter, but nobody knows for sure. Current surveys put the refuge’s population at 245 cranes. That represents a loss of 38 birds from Stehn’s final census in 2010 and 2011, though the U.S. Parks and Wildlife Service points out that it’s difficult to compare the numbers given the different methods of data collection and harsh drought conditions of the previous winter. “I think last year was a bad year,” Stehn said. “I’m frustrated that the refuge didn’t document that. They fell flat on their face.”

Stehn is concerned about more than the end of an annual count, though. He worries that invasive black mangrove and rising sea levels could wipe out the cranes’ marshes. Perhaps Stehn’s problem is that he stayed at the Aransas refuge too long, but after he arrived thirty years ago, he never left. Images of whooping cranes decorate his walls, his T-shirts, and his coffee mugs. Looking back at his career, he says, with a hint of wonder, “I just got enamored with cranes.”![]()

Remote Tracking of Aransas-Wood Buffalo Whooping Cranes

June 25, 2012by: Chester McConnell, WCCA

Several government agencies and private organizations have formed the Whooping Crane Tracking Partnership (WCTP) to determine, more specifically, the migration path and activities of whooping cranes that migrate between Aransas National Wildlife Refuge, Texas and Wood Buffalo National Park, Canada. The WCTP trapped whooping cranes, made health checks and collected blood and other biological samples. Then they placed on each crane a Global Positioning System with Platform Transmitting Terminals device as a way to identify migration pathways for the Aransas-Wood Buffalo whooping cranes. WCTP recently released a report covering the 2011 breeding season and fall migration.

The WCTP gathered detailed information concerning where 23 whooping cranes spent time at and the length of time they remained at various locations during the 2011 breeding season and fall migration. Highlight from the report described one adult crane nesting during the summer 2011 but was observed without young during fall migration. Tracking data showed one 1-year- crane spending the summer in southern Saskatchewan and northern North Dakota.

Migration travel time between the Wood Buffalo summer nesting area in Canada and the wintering habitat at Aransas, Texas varied for different whooping cranes. Some of the 23 cranes with GPS were migrating during a 79 day period. The first cranes began migration on September 10 and all cranes that completed migration arrived on the Texas coast by November 27.

Mortality during migration is important to understand. The WCTP confirmed one mortality of the 23 GPS whooping cranes during migration. This was a juvenile crane that died in early November. WCTP plans future trapping efforts for August 2012 at Wood Buffalo National Park and during winter at Aransas National Wildlife Refuge. Hopefully the study will help to better understand whooping cranes and management needs. The report includes much interesting information.

The entire WCTP report with a map can be read by clicking on the following link: http://www.cranetrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/Whooping-Crane-Tracking-Partnership-2011-breeding-and-fall-update.pdf

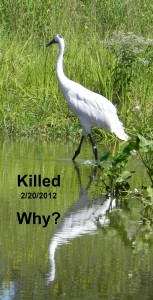

Man Indicted For Killing Whooping Crane and Witness Tampering in South Dakota

June 18, 2012June 18, 2012

United States Attorney Brendan V. Johnson announced that a Miller, South Dakota, man has been indicted by a federal grand jury for Violating the Migratory Bird Treaty Act and Witness Tampering.

Jeff G. Blachford (Facebook Profile), age 25, was indicted by a federal grand jury on June 12, 2012. He appeared before United States Magistrate Judge Mark A. Moreno on June 15, 2012, and pled not guilty to the indictment. The maximum penalty upon conviction is 20 years’ custody, a $250,000 fine, or both; not more than 3 years of supervised release; and a $100 special assessment. Restitution may also be ordered.

The charges relate to allegations that in April 2012, Blachford shot and killed an endangered whooping crane and one hawk in Hand County, approximately 17 miles southwest of Miller, South Dakota. Blachford is further alleged to have corruptly persuaded a witness to withhold information from law enforcement officials. The charges are merely accusations, and Blachford is presumed innocent until and unless proven guilty.

Whooping cranes are one of the rarest birds in the world with a total population of approximately 600 individuals. The whooping crane killed in this investigation was one of about 300 endangered cranes that migrate from wintering grounds along the gulf coast of Texas to the Woods Buffalo State Park located in Alberta and the Northwest Territories of Canada. This population of whooping cranes is the only self-sustaining population in the world.

The investigation is being conducted by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services and South Dakota Game Fish and Parks. The case is being prosecuted by Assistant United States Attorney Meghan N. Dilges. Blachford was released on bond pending trial.

The Whooping Crane Conservation Association is very pleased with the indictment by the federal grand jury. However, the Association cautions that the case must still be brought to trial and a conviction made before justice is served. The Association has a $10,000 Reward for the “conviction” of the person(s) responsible for the senseless killing of the whooping crane. Contributions to the Reward Fund are stil needed. The public is urged to donate to the fund to help convict this and other whooper killings.

Donations (which are tax-deductible) are being requested for the Whooping Crane Conservation Association’s Reward Account. The public is encouraged to donate to this fund. Donations should be mailed to Whooping Crane Conservation Association, 2139 Kennedy Avenue, Loveland, CO, USA 80538 or to donate by credit card click on the link: https://whoopingcrane.com/whooping-crane-shot-10000-reward/

Lobstick Whooping Crane Feared Shot In South Dakota

June 7, 2012Article from Northern Journal, Fort Smith, NT Canada (www.srj.ca).

By CHRIS TALBOT, Northern Journal Reporter, • Tue, Jun 05, 2012

Fort Smith local Ronnie Schaefer believes the whooping crane (like the one pictured here) shot in South Dakota was one of the famous Lobstick pair. (Photo: Klaus Nigge)

A whooping crane recently shot in South Dakota may be one of the famous Lobstick cranes that nest north of Wood Buffalo National Park, according to a Fort Smith man. Ronnie Schaefer, who has observed the cranes for many years, told Northern Journal he believes the crane shot en route to Canada is one of the Lobstick pair. The pair has made the Fox Hole prairie on Salt River First Nation land home for 19 years, usually arriving in the first two weeks of May. They have not arrived yet.

Another reason Schaefer believes it may be one of the Lobstick birds is because they are not tagged. Although not confirmed, it is believed by Parks Canada that the crane shot in South Dakota was likewise not tagged. Schaefer said he is trying to clarify that, but so far, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), which is investigating the shooting, has been tight-lipped about the case.

Brad Merrill, a spokesperson for FWS Mountain-Prairie Region, said it is FWS policy not to discuss cases still under investigation. He did confirm that the crane was travelling with another adult and a juvenile, both of which were seen in the same corn field where the shooting occurred. What happened to the other cranes is unknown.

“It’s a big loss for us because they’re a recognized pair from here to Aransas,” Schaefer said.

The Fox Hole prairie is the traditional nesting ground for another pair of whooping cranes, which Schaefer said has already arrived and settled in. A new nesting pair has also settled in the area, but Schaefer noted it is not the Lobstick pair.

Others believe it is too early to tell for sure if the killed bird was indeed one of the famous cranes.

“That would be really tough to deduce based on what we know,” Dan Alonzo, refuge manager at Aransas National Wildlife Refuge, told The Journal.

Chester McConnell, trustee emeritus at the Whooping Crane Conservation Association, told The Journal it would be a great loss should the shot crane be one of the Lobstick pair.

“It would be, but I’m not certain (Schaefer) would be correct on that. I don’t know what information he has, but the cranes haven’t been long settling in and some of them would take a little while to settle into nesting,” McConnell said.

According to McConnell, whooping cranes do not all fly in and start building nests right away. Though their time to nest is short, they are known to “fool around.”

With only about 300 whooping cranes migrating between Wood Buffalo National Park and Aransas National Wildlife Refuge in Texas, the loss of any of the endangered birds is significant, Alonzo said. There are approximately 500 whooping cranes left in the world.

“It would be the equivalent to the loss of any other bird,” Alonzo said. “Any loss is significant. We want to do anything to deter that. The Lobstick or any other pair is just as important.”

One death of many

The shooting of the whooping crane in South Dakota is the latest in a dozen confirmed shootings of the species since 1951. Approximately 80 whooping cranes of the western migratory flock have also gone missing during that time, their fates unknown, McConnell said.

Cranes that do not die of natural causes are most likely to be killed flying into power lines or electrified fences, he said, but some people shoot the birds out of malice.

The eastern migratory and non-migratory Louisiana populations suffer even more from human predation. McConnell noted 11 cranes in the eastern and Louisiana populations have been shot in the last two years. Many of those cases are still unsolved. The most recent incident prior to the April 20 shooting in South Dakota was the January 2012 shooting of a male whooping crane in Knox County, Indiana. The crane was spotlighted and shot, according to FWS. Charges are pending against two men in their early twenties.

————————————————————————————————————————

The Whooping Crane Conservation Association has established a REWARD fund to raise $10,000 for conviction of the killer of the whooping crane in South Dakota on May 20, 2012. Donations are still needed. Click on the following link to read details of the Reward fund and how you can help: https://whoopingcrane.com/whooping-crane-shot-10000-reward/

Whooping Crane Killing – One Investigation Completed–More to Go

May 17, 2012Reported by: Whooping Crane Conservation Association

Indiana Conservation Officers, with assistance from U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service agents, have completed an investigation into the killing of a male whooping crane in early January 2012 in Knox County, Indiana.

The Knox County Prosecutor is reviewing the case, and charges are pending against Jason R. McCarter, 21, of Wheatland, and John C. Burke, 23, of Monroe City.

According to the case report filed with the prosecutor, ICO Joe Haywood received information in mid-January that a whooping crane had been spotlighted at night and shot and killed with a high-powered rifle.

The ensuing investigation involved multiple law enforcement agencies, wildlife biologists and private individuals and provided information that identified the suspects and also linked the bird to a federal program to reintroduce whooping cranes in the eastern United States.

Whooping cranes are an endangered species protected by both state and federal laws. Efforts to save whooping cranes began after their nationwide population dwindled to 15 birds in 1941, according to the Whooping Crane Conservation Association.

The Association advises there are approximately 600 whooping cranes in existence, with approximately 445 in the wild. Approximately 300 are in the original western flock that migrates between Aransas NWR, Texas and Wood Buffalo National Park, Canada. Also more than 100 are in the eastern reintroduction flock that travels through Indiana on a migratory path between Wisconsin and Florida. Roughly 150 captive-raised birds are used in the reintroduction programs at a cost exceeding $100,000 per bird.

The whooping crane shot in Knox County, Indiana was part of a nesting pair that was taught its migratory path by ultra-light aircraft. For more on the bird, see: www.learner.org/jnorth/tm/crane/08/BandingCodes827.html

An investigation into the killing of a second whooping crane in Jackson County, Indiana continues. Anyone with information can call the Turn In A Poacher hotline at 1-800-TIP-IDNR.

The Whooping Crane Conservation Association reminds the public that the Indiana case is just one of four cases. Three more whooping crane killing cases are still under investigation. One case is in South Dakota, one in Indiana and one in Alabama.

The whooping crane killed in South Dakota on April 20, was a member of the original wild western flock. The migrating adult bird was traveling with two additional whooping cranes before being shot with a high-power rifle as it was standing in a corn field. The Whooping Crane Conservation Association will pay a reward not to exceed $10,000 to anyone who provides information which leads to the conviction of any individuals responsible for the killing of the whooping crane which took place on the afternoon of Friday, April 20, 2012 along 354th Avenue, approximately 17 miles southwest of Miller, South Dakota.

original wild western flock. The migrating adult bird was traveling with two additional whooping cranes before being shot with a high-power rifle as it was standing in a corn field. The Whooping Crane Conservation Association will pay a reward not to exceed $10,000 to anyone who provides information which leads to the conviction of any individuals responsible for the killing of the whooping crane which took place on the afternoon of Friday, April 20, 2012 along 354th Avenue, approximately 17 miles southwest of Miller, South Dakota.

The purpose of all rewards is to encourage the public to share information they might have about criminal activities involving whooping cranes. Federal, State, Provincial, and other public law enforcement personnel, and criminal accomplices who turn “states” evidence to avoid prosecution, shall not be eligible for this reward. If more than one informant is key to solving a specific case, the reward will be equally divided between the informants.

Anyone with information should call either the 24-hour “Turn in a Poacher Hotline” at 1-888-OVERBAG (683-7224) or the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service at 605-224-9045 to report any information which will aid officers in the apprehension of the shooter. Callers can remain anonymous.

Eleven whooping cranes of the experimental Eastern Migratory population and non-migratory Louisiana population have been shot in the last two years. The Alabama case of January 2011 is still active. The Louisiana shootings have been solved by State Law Enforcement personnel and a reward will not be involved. One case is still active in Indiana. In Indiana the State has offered $2,500, the Fish and Wildlife Service $2,500 and the Humane Society $2,500 in reward.

Donations (which are tax-deductible) are being requested for the Whooping Crane Conservation Association’s Reward Account. The public is encouraged to donate to this fund. Donations should be mailed to Whooping Crane Conservation Association, 2139 Kennedy Avenue, Loveland, CO, USA 80538 or to donate by credit card click on the link: https://whoopingcrane.com/whooping-crane-shot-10000-reward/

THE IDIOTS ARE WINNING …

May 7, 2012By Joe Duff, Operation Migration*

Another Whooping crane was shot last week, this one in South Dakota.

It was an adult, in the company of two others and on its way from the gulf coast of Texas to the Wood Buffalo National Park in northern Canada. Whooping cranes are not colonial birds that flock together in large numbers. Instead they generally migrate in family groups, so the two others could have been its mate and their chick from last year. They still had another 1000 miles to go to reach their nesting grounds. If the third bird was their offspring from last season, they would have shooed it off before they re-claimed their territory and built a nest for this year’s eggs.

Whooping cranes are anything but camouflaged. At five feet tall in bright white feathers, they stand out like a beacon and make an obvious target for those so inclined. This bird was shot with a high powered rifle while it stood in a field. That brings the number of Whooping cranes shot in the last two and a half years to twelve.

I purposely used the word “shot” so it wouldn’t be confused with “hunted.” There are two words to describe the activity of using a gun to harvest wild prey. One is hunting and it describes the legal taking of game species for sport. The other word is poaching but that has connotations of stealing something for food and that was not the case here or in any of the other shootings. There should be another name for people who shoot things just to kill them.

It is hard to understand why someone would want to kill a Whooping crane simply because they can. Maybe it’s an act of defiance or a belief that the rules apply to everyone but them, or perhaps it’s displaced aggression; they kill a Whooping crane because they can’t kill their boss. One of the arguments we have heard consistently is that they didn’t know what it was and if we had done a better job of educating people, it wouldn’t happen. Now there is a warped sense of privilege for you.

Many words can be used to describe that attitude. The list starts with terms like self-serving and arrogant and degrades to adjectives like ignorant. Then it drops below the line that is only printable if it’s scrawled on the wall of a public urinal.

The one term you can’t use to describe them is “hunter.” Real hunters obey the rules; in fact they often make the rules. They are also responsible for most of the conservation work that takes place. Hunting groups like Ducks Unlimited and the Wild Turkey Federation protect thousands of acres of habitat while a tax on firearms and ammunition known as the Pittman Robertson Act has provided over 5 billion dollars to wildlife projects. But twelve birds in just over two years is far too many and maybe it is time we asked hunting organizations for help. Perhaps they would welcome the opportunity to educate the morons with the twisted values.

Or maybe you can’t reach people that stupid. They say that if you make it idiot proof, they will simply make a better idiot.

* This article reprinted with permission of Operation Migration

All Whooping Cranes Migrating To Canada

April 27, 2012- By: Chester McConnell, Whooping Crane Conservation Association